Copy link

Multiple Gestation Pregnancy

Last updated: 10/23/2025

Key Points

- The incidence of multiple gestations has increased dramatically over recent decades.1,2

- Multiple gestations are associated with a variety of complications, with prematurity being the most critical fetal complication and hemorrhage and preeclampsia being the most common maternal complications.1

- Neuraxial analgesia and anesthesia are preferred for the delivery of multiple gestations, whether vaginal or via cesarean.1,6

Introduction

Incidence and Trends1,2,3

- The incidence of multiple gestations has increased over the past several decades, primarily due to assisted reproductive technologies (ART) and advanced maternal age.

- Twin births: Approximately 31 per 1,000 live births in the United States (US) (Center for Disease Control and Prevention, 2023) Link, a fourfold increase since the 1980s

- Triplet and higher-order multiples: Approximately 74 per 100,000 live births, though rates have declined since peaking in the 1990s as ART practices have shifted to single-embryo transfer

Zygosity1,2,3

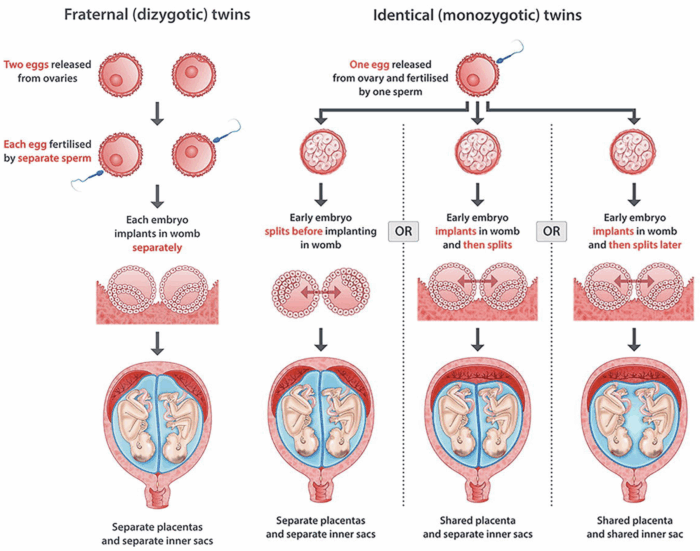

- Dizygotic (fraternal) twins arise from fertilization of two separate ova; incidence varies by maternal factors (age, ethnicity, family history, fertility treatments) (Figure 1).

- Monozygotic (identical) twins result from division of a single fertilized ovum; incidence is stable worldwide at ~3–4 per 1,000 live births and unaffected by maternal age or ART (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Dizygotic and monozygotic twins. Source: Mashamba T. Types of multiple pregnancy. IntechOpen. CC-BY 3.0. Link

Geographic and Demographic Variations2,4

- Higher twinning rates are observed in non-Hispanic Black populations compared with White or Hispanic populations in the US.

- Maternal age of 35 years or older and higher parity are associated with increased risk of dizygotic twinning.

- Use of ART or ovulation induction significantly increases the risk of multiple gestations, especially when multiple embryos are transferred.

Perinatal Outcomes1-4

- Multiple gestations account for 20% of all preterm births and ~10% of perinatal mortality despite representing only ~3% of all pregnancies.

- Cesarean delivery rates are substantially higher (≈70% for twins; more than 90% for triplets).

- Low birth weight (less than 2,500 g) occurs in ~60% of twin births and more than 95% of higher-order multiples.

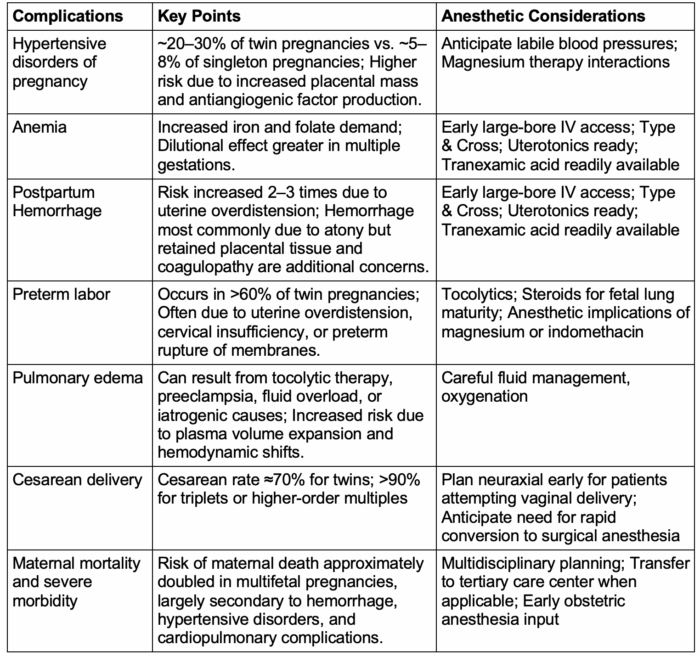

Maternal Morbidity2-4,6

- Parturients with multifetal gestations have 2–3 times the risk of hypertensive disorders, anemia, hemorrhage, and cesarean delivery.

- Maternal mortality is modestly increased, primarily driven by hemorrhage, hypertensive disease, and cardiopulmonary complications.

Review of Multiple Gestations

- Monochorionic-monoamniotic (MoMo) twins: share one placenta and one amniotic sac

- Reported incidence of 8 per 100,000 pregnancies

- Delivery is recommended between 32 and 34 weeks.

- Risks include umbilical cord entanglement, compression, and twin-to-twin transfusion syndrome (TTTS). Cord entanglement can lead to fetal death. Perinatal mortality is reported to be between 30% and 40% due to high risks.

- Monochorionic-diamniotic (MoDi) twins share a single placenta but have separate amniotic sacs.

- Account for 1 in 5 twin pregnancies

- Risks: There is still a risk for TTTS, unequal placental sharing, but lower risks for umbilical cord entanglement than Mo/Mo twins. Complications are estimated to affect around 15% of Mo-Di pregnancies. Fetal growth discordance is less than 20%.

- Dichorionic-dichorionic (DiDi) twins each have their own placenta and amniotic sac.

- Around 18% in the US for all twin gestations

- The most common type occurs in both fraternal (dizygotic) and some identical (early split) twins.

- DiDi represent the lowest risk. Preterm birth and growth discordance can occur.

- Tri-/Quad-/Higher Multiples

- Triplets, quadruplets, may exhibit mixed patterns and could have one shared placenta or others having multiple sacs.

- Occurs in 73.8 per 100,000 live births

- Most often associated with ART, but not always.

- Risks: Increased risk due to prematurity, low birth weight, and varied chorionic and amniotic configurations.

Maternal Complications

Table 1. Maternal complications in multiple pregnancies1,3,5

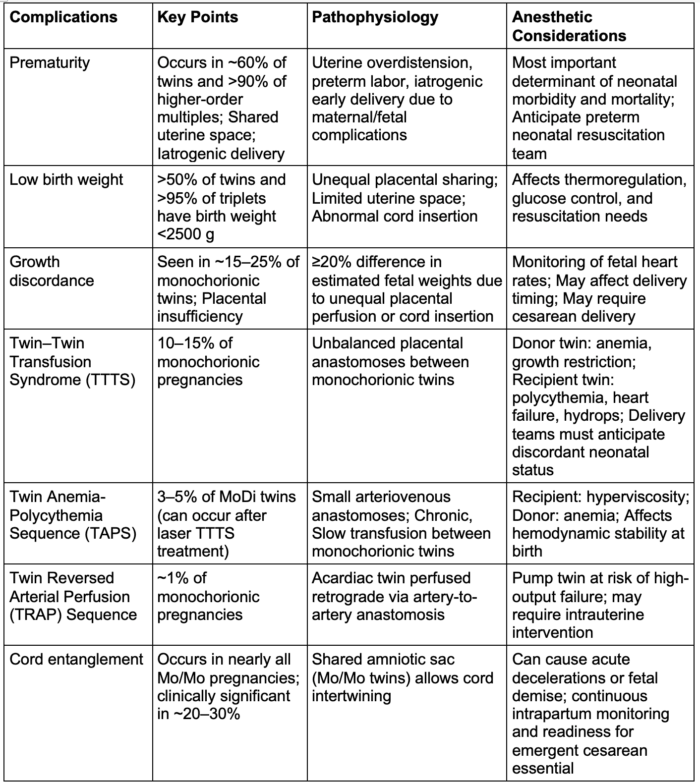

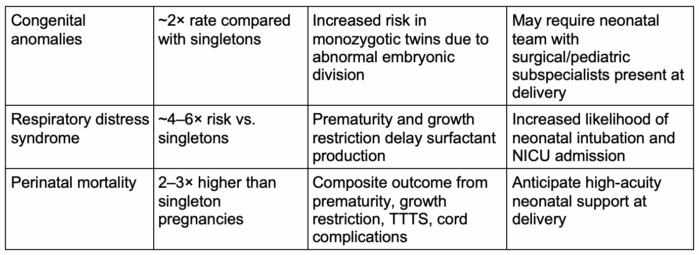

Neonatal Complications

Table 2. Neonatal complications in multiple pregnancies1,3,5-7

Intrapartum and Anesthetic Management

Anesthetic Considerations1,5

• Early neuraxial analgesia is recommended for all laboring patients with multiple gestations to provide optimal pain control and facilitate rapid conversion to surgical anesthesia if emergent cesarean or breech extraction is required.3,7

• A functioning epidural is advantageous for extending to surgical anesthesia if the delivery of twin B necessitates operative intervention.7

• General anesthesia (GA) is reserved for patients with contraindications to neuraxial, failed/insufficient block, and/or emergent delivery. Airway edema, difficult intubation, and increased risk of aspiration in laboring patients should be anticipated.2,3,7

Preparation and Team Readiness1,5

- Delivery of twins or higher-order multiples should occur in an operating room or similarly equipped setting with immediate access to anesthesia, obstetrics, and two neonatal teams.3,7

- Establish two large-bore IV lines, obtain type and screen/crossmatch, and ensure uterotonic agents and tranexamic acid (TXA) are readily available.3

- Continuous fetal heart rate monitoring should be maintained for both fetuses during labor and the presentation of twin B after delivery of twin A should be reassessed using ultrasound.3

Delivery Planning1,5,7

- Timing and mode of delivery are guided by chronicity and presentation, excluding preeclampsia or maternal comorbidities/diagnoses.

- DiDi: 37-38 weeks

- MoDi: 34-37 weeks

- MoMo: 32-34 weeks, typically via cesarean

- Triplets or higher: 32-24 weeks

- For planned vaginal delivery, ensure adequate neuraxial block and readiness to convert to cesarean if indicated.

- Nitroglycerin (50-100micrograms IV) or transient increases in volatile agent concentration can be used for uterine relaxation during difficult extraction or entrapment of twin B, followed by prompt uterotonic administration.7

Hemorrhage and Hemodynamic Considerations1,5

- Risk of postpartum hemorrhage (PPH) is 2-3x higher due to uterine overdistension and atony.7

- An active management of the third stage approach should be employed with oxytocin infusion, early use of TXA, and readiness for additional uterotonics.3,7

- Excessive crystalloid administration should be avoided to reduce the risk of pulmonary edema, particularly in patients receiving magnesium or with hypertensive disorders.2

Hypertensive Disorders and Magnesium Therapy1,3,5

- Preeclampsia is more common in multifetal gestations; labile blood pressure and exaggerated hemodynamic responses to induction or delivery should be anticipated.2

- Magnesium sulfate therapy potentiates nondepolarizing neuromuscular blockers and may cause maternal hypotonia and respiratory depression; dose adjustments and vigilant monitoring are essential if GA is needed.2

Postpartum Care1,3,5

- Close monitoring for delayed PPH and pulmonary edema in the immediate postpartum period should be maintained.

- Multimodal postoperative analgesia should be provided after cesarean delivery; if neuraxial is utilized, neuraxial morphine should be provided.

Fetal Reduction Procedures6,7

- Fetal (multifetal) reduction is a procedure to decrease the number of fetuses in a multifetal pregnancy (typically triplets or higher) to improve maternal and fetal outcomes.

- These procedures are usually performed under ultrasound guidance via transabdominal or transcervical approach, most commonly in the first or early second trimester (11–14 weeks).

- Indications:

- Higher-order multiple gestation (≥3 fetuses) is associated with increased risks of prematurity, preeclampsia, growth restriction, and maternal morbidity.

- It may also be indicated for selective reduction in the presence of severe fetal anomalies or discordant pathology (e.g., twin reversed arterial perfusion, anencephaly, lethal anomaly in one twin).

- Techniques:

- Injection of potassium chloride (KCl) into the fetal heart (intracardiac) or umbilical vein under continuous ultrasound guidance

- In monochorionic pregnancies, selective cord occlusion techniques (radiofrequency ablation, bipolar cord coagulation, or laser ablation) are preferred because vascular anastomoses can endanger the co-twin if KCl is used.

- Anesthetic/Periprocedural Considerations:

- These are usually performed under local anesthesia with mild sedation (e.g., short-acting benzodiazepine or opioid). GA is rarely needed.

- Maternal monitoring: Noninvasive blood pressure, pulse oximetry; avoid hypotension or hypoxia to reduce risk of fetal compromise

- Analgesia and anxiety management: Maternal anxiety can be significant; short-acting anxiolytics and clear counseling are important.

- Ultrasound guidance by a maternal-fetal medicine specialist is mandatory; the procedure is typically performed in an outpatient or day-surgery setting.

- Antibiotic prophylaxis is often given; tocolytics may be used post-procedure in selected cases.

- The anesthesia team role is to provide sedation/analgesia as needed, monitor maternal hemodynamics, and manage potential complications (vasovagal response, bleeding, uterine irritability).

- It is important to understand the obstetric context, as these patients often return later for high-risk delivery and may have residual procedural anxiety or grief considerations.

- Risks and Outcomes:

- Procedure-related pregnancy loss occurs in ~4–8% of cases, depending on the number of fetuses and technique.

- Reduction to twins or singletons markedly reduces the risk of preterm birth and maternal complications compared to continuing high-order gestation.

References

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Practice bulletin No. 231: Multifetal gestations: Twin, triplet, and higher-order multifetal pregnancies. Obstet Gynecol. 2021;137(6):e178-e194. PubMed

- Martin JA, Osterman MJK, Hamilton BE, et al. Births: Final data for 2022. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2024;73(2):1–49. PubMed

- Simpson LL. Update on management and outcomes of monochorionic twin pregnancies. Obstet Gynecol. 2025;145(5):486-502. PubMed

- Martin JA, Osterman MJK. Declines in triplet and higher-order multiple births in the United States, 1998-2023. NCHS Data Brief. 2024;(512):CS354442. PubMed

- Farrer JR, Peralta FM. Anaesthesia for the parturient with multiple gestations. BJA Educ. 2022;22(8):306-11. PubMed

- Raffé-Devine J, Somerset DA, Metcalfe A, Cairncross ZF. Maternal, fetal, and neonatal outcomes of elective fetal reduction among multiple gestation pregnancies: A systematic review. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2022;44(1):60-70. PubMed

- Weitzner O, Barrett J, Murphy KE, et al. National and international guidelines on the management of twin pregnancies: a comparative review. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2023;229(6):577-598. PubMed

Other References

Copyright Information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.