Copy link

Anesthesia for Maternal-Fetal Procedures: An Overview

Last updated: 02/14/2024

Key Points

- Maternal-fetal surgeries include a wide scope of procedures ranging from minimally invasive intrauterine fetal interventions, mid-gestation fetal surgeries, and ex-utero intrapartum treatment (EXIT) procedures.

- Minimally invasive procedures are usually performed during midgestation and are typically amenable to monitored anesthesia care.

- Midgestation fetal surgeries and EXIT procedures are usually performed with the mother under general anesthesia, with particular care to maintain uterine atony throughout the procedure.

Introduction

- The anesthetic management of maternal-fetal surgery is guided by integrating the principles of obstetric and pediatric anesthesia and applying them to the specific needs of the planned procedure, the pathophysiology of the fetus, and patient comorbidities.

- These procedures involve collaborative efforts from multidisciplinary teams, including but not limited to, maternal-fetal medicine, pediatric surgery and subspecialties, obstetric and pediatric anesthesiology, pediatric cardiology, radiology, and neonatology.1-3

- The goals of therapy fall into three categories. First is to prevent intrauterine fetal demise (e.g., debulking a sacrococcygeal teratoma), second is to improve postnatal health and quality of life (e.g., closure of myelomeningocele), and third is to allow a successful transition to extrauterine life (e.g., EXIT to secure an airway obstructed by tumor).

- The development of hydrops fetalis is often the factor that will tip the risk-benefit analysis towards a maternal-fetal intervention.

Pathologies Requiring Maternal-Fetal Intervention

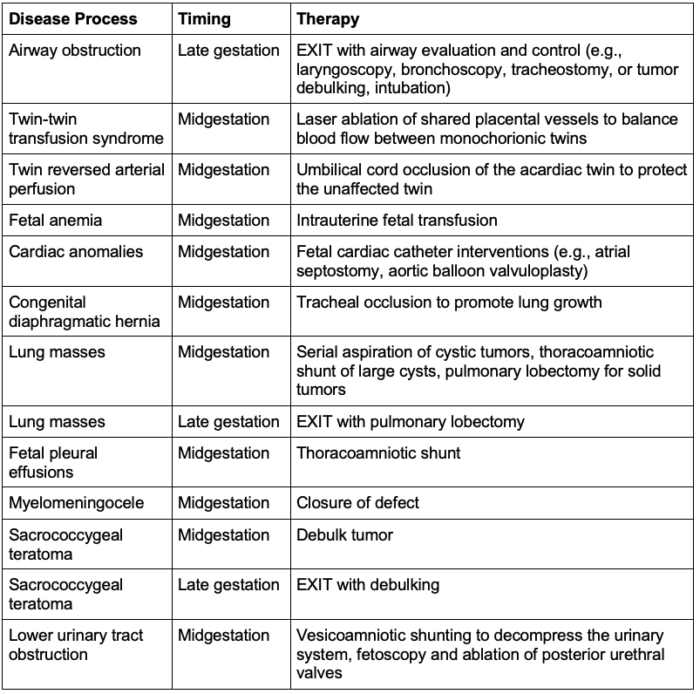

- Common disease processes amenable to maternal-fetal interventions are listed in Table 1.

Table 1. Common disease processes amenable to fetal therapy

Anesthetic Considerations

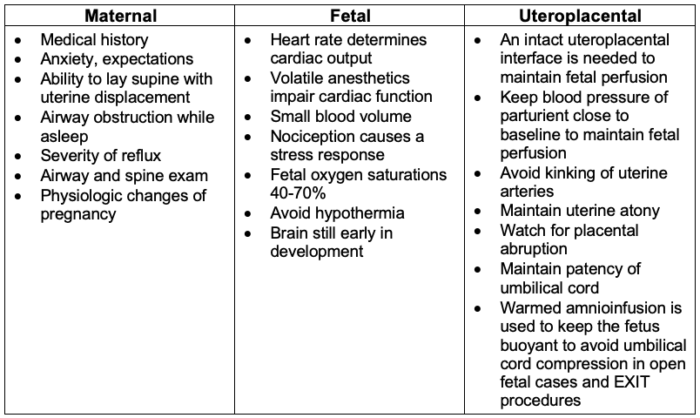

- The major anesthetic considerations for maternal-fetal interventions are listed in Table 2.

Table 2. Maternal, fetal, and uteroplacental considerations1-3

Surgical Considerations

- Approaches and techniques will vary, and close communication with surgical team helps with the planning.

- The anesthesia team must understand both the goals of therapy and the specific steps needed to accomplish the goal.

- In minimally invasive procedures, the insertion of sheaths and needles is dictated by the placental location and fetal position.

- Some procedures will involve a laparotomy with the insertion of fetoscopes after exposure of uterus.

- Open fetal procedures and EXIT procedures involve a maternal laparotomy, followed by mapping of the placenta and subsequent hysterotomy to expose the fetus.

- In most cases, the goal is for the mother to carry the pregnancy as close to term as possible.

- For EXIT procedures, which are done in late gestation, the fetus is delivered at the end of the procedure.

Anesthetic Management

Minimally Invasive Interventions

- Light sedation with infiltration of local anesthesia often accomplishes the goals.

- Combinations of benzodiazepines, opioids, propofol, or dexmedetomidine have been used successfully, and the choice will often depend on institutional preferences.

- Maternal oversedation should be avoided to prevent troubles with aspiration, hypercarbia, and airway obstruction.

- Neuraxial and general anesthesia may be chosen depending on patient factors, surgical needs, or institutional preferences.

- Left uterine displacement is often used to alleviate aortocaval compression, but depending on the location of the placenta and the planned route to access the fetus, sometimes the maternal position must be changed to facilitate the procedure.

- The anesthesia team should always be ready for emergent conversion to general anesthesia.

Open Fetal and Laparotomy-Assisted Fetoscopy

- Laparotomy-assisted fetoscopy is primarily used for fetoscopic closure of neural tube defects, while most open fetal surgical approaches involve both laparotomy and hysterotomy.

- Anesthetic management of both techniques is similar. There will often be a pediatric anesthesia team dedicated to the fetus and an obstetric anesthesia team dedicated to maternal needs.

- Epidurals are commonly used for postoperative analgesia.

- In the operating room, after ensuring left uterine displacement, a rapid sequence induction is performed to facilitate endotracheal intubation.

- In addition to standard American Society of Anesthesiologists monitors, invasive blood pressure monitoring is commonly used.

- Large-bore intravenous access should be obtained since the uterine atony that is required for these procedures presents an increased risk for hemorrhage.

- Uterine atony can be accomplished with nitroglycerin, volatile anesthetic, magnesium bolus and infusion to aid with uterine relaxation.

- A cocktail of fentanyl, atropine, and nondepolarizing neuromuscular blocking agents is used as an intramuscular fetal injection.

- Emergency resuscitation medication for the fetus, including unit doses of epinephrine and atropine, should be readily available.

- Judicious fluid administration is critical to avoid postoperative pulmonary edema.

- Vasopressors such as phenylephrine can be used to support maternal blood pressure.

- Some institutions minimize volatile anesthetics to attenuate fetal cardiac depression.

- Various combinations of propofol and remifentanil have been used.

- Total intravenous anesthesia and primarily neuraxial-based anesthetic techniques have also been used, but less commonly.

- Fetal echocardiography helps monitor the fetal heart rate, patency of the ductus arteriosus, cardiac filling, and function.

- Ultrasound can also monitor flow in the umbilical cord.

- Some cases may require fetal vascular access.

- Fetal blood should be type O negative, and the units should be crossmatched against the mother’s blood sample.

- The epidural is bolused towards the end of the procedure to avoid intraoperative hypotension.

- The patient should be extubated when fully awake.

EXIT

- Anesthetic management of the parturient starts in a similar fashion to that for midgestation fetal surgeries, but there is no need for fluid restriction or magnesium administration.4

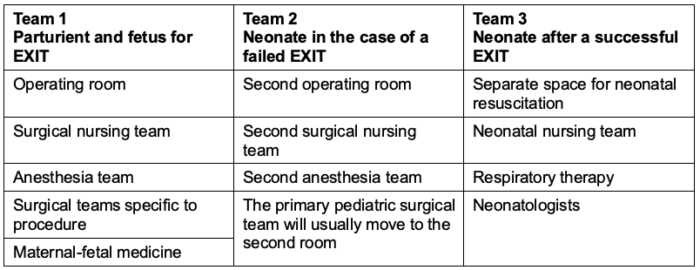

- Three teams are involved in EXIT procedures (Table 3).

- Each team has a primary location and responsibility, but all the team members can intermingle and collaborate.

- The first team is for the parturient and fetus for the EXIT procedure itself.

- A second team is prepared in a second operating room and needs to be ready to care for the neonate if complications arise, necessitating rushing the EXIT or performing an emergent delivery.

- A third team from the neonatal intensive care unit should be present to continue resuscitation after either a successful EXIT or an emergent activation of the second operating room team.

- The fetal status may be monitored by pulse oximetry, echocardiography, and possibly even point-of-care blood testing.

- Most fetuses will benefit from peripheral intravenous access.

- The fetus is intubated but not ventilated until the decision has been made to deliver.

- Oxytocin, methylergonovine, and carboprost should be readily available to reestablish uterine tone once the fetus is delivered.

Table 3. Teams and requirements for an EXIT procedure

References

- Liu CA, Low S, Tran KM. Anaesthesia for fetal interventions. BJA Educ. 2023;23(5):162-71. PubMed

- Ferschl MB, Jain RR. Fetal and neonatal anesthesia. Clin Perinatol. 2022;49(4):821-34. PubMed

- Chatterjee D, Arendt KW, Moldenhauer JS, et al. Anesthesia for maternal–fetal interventions: A consensus statement from the American Society of Anesthesiologists Committees on Obstetric and Pediatric Anesthesiology and the North American Fetal Therapy Network. Anesth Analg. 2020;132(4):1164-73. PubMed

- Lin EE, Moldenhauer JS, Tran KM, Cohen DE, Adzick NS. Anesthetic management of 65 cases of ex utero intrapartum therapy. Anesth Analg. 2016;123(2):411-7. PubMed

Copyright Information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.