Copy link

Pain Management in Burns

Last updated: 01/16/2024

Key Points

- Pain management in burn patients is challenging and involves a complex interplay between tissue damage and healing, repeated procedures, anxiety, and a long course to recovery.

- A multimodal pain regimen with opioids, acetaminophen, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, benzodiazepines, and ketamine can be helpful in managing pain in these patients.

- Regional anesthesia and nonpharmacological approaches should be used when appropriate.

Introduction

- In the United States, over 450,000 burn incidents receive medical treatment every year. Many will be cared for by anesthesiologists in the operating room.1

- The skin is an important organ for temperature regulation, sensation, defense against pathogens, as well as fluid balance. Thermal injury causes a breakdown in those barriers.

- Major burns result in an inflammatory response characterized by an early burn shock phase followed by a hyperdynamic, hypermetabolic phase. Please see the OA summaries on “Burn Injuries: Initial Evaluation and Management” Link and “Anesthesia Considerations for Burn Surgery” Link for more details.

- Briefly, the hypovolemic stage results in decreased perfusion, decreased drug metabolism, and decreased protein binding. These consequences require caution when administering medications that can have hemodynamic effects.

- The subsequent hypermetabolic stage results in increased hepatic and renal blood flow, increased drug metabolism, large volume of distribution, upregulation of enzymes, drug tolerance, and increased pain response. During this stage, patients require increasing doses of medications as well as a multimodal approach.

This summary will focus on pain management for burn injuries.

Pain Following Burns

- Pain management for burns is challenging and involves a complex interplay between tissue damage and healing, repeated procedures, anxiety, and a long course to recovery.

- Despite advances in modern burn care, suboptimal pain management is common, secondary to variability of pain thresholds and lack of standardized approaches.2

- Typically, deeper, full-thickness burns are thought to be less painful than superficial and partial-thickness burns secondary to afferent nerve destruction. However, full-thickness burns often require debridement and skin grafting, which leads to substantial pain.2

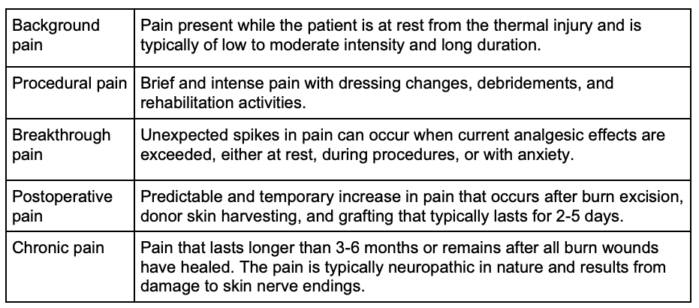

- The Patterson burn pain paradigm is based upon five phases of burn pain occurrence and helps guide pain management in burn patients3 (Table 1).

Table 1. Patterson burn pain paradigm. Adapted from Patterson DR, Sharar SR. Burn pain. In: Fishman SM, Balantyne JC, Rathmell JP (eds) Bonica’s Management of Pain, 4th edition. Philadelphia, PA. Lippincott Williams and Wilkins, 2010. 754.

Psychological Trauma

- In addition to the physical pain caused by the burns, there is a significant amount of anxiety and stress at baseline, as well as the pain associated with repeated procedures, such as debridements and dressing changes.

- Although patients may have had repeated procedures, such as skin grafts and debridements, it is important to communicate the plan to the patient with each anesthetic. It may be beneficial to ask if the patient has any concerns and allow them to convey negative experiences from previous anesthetics.

- Posttraumatic stress disorder can develop after major burn injuries.

Pain Assessment

- Pain assessment requires an understanding of the acute, chronic, and procedural forms of burn-related pain.

- Pain assessment should be performed several times a day and during various phases of care.4

- Patient-reported tools, such as the visual analog scale and the numeric rating scale, are commonly used as guides for pain management in burn patients.2 In nonverbal patients (young children and noncommunicative adults), observational scales and physiological indicators, such as heart rate and blood pressure, are used to gauge pain.

- The American Burn Association recommends the Burn Specific Pain Anxiety Scale during the course of an acute burn hospitalization.4 It is a validated tool for the burn patient population. The Critical Care Pain Observation Tool can be used when a patient is not able to interact with care providers.4

Pharmacological Considerations

- Plasma protein loss through injured skin and further dilution of plasma proteins by resuscitation fluids decrease the albumin concentration.1

- There is an increase in the volume of distribution of the most commonly used medications (propofol, fentanyl, muscle relaxants).1

- During the acute injury phase, decreased cardiac output and resulting decreased renal and hepatic blood flow reduce the elimination of some drugs by the kidney and liver.

- In the hyperdynamic phase, there is increased cardiac output and blood flow to the kidneys and liver. Therefore, there is increased clearance of some drugs, requiring higher doses.

- Hepatic enzyme activity is often altered, resulting in impaired phase 1 reactions.

- The pharmacological treatment of pain in burn patients depends on several factors:

- Patient’s age

- Time elapsed since the burn

- Mechanism of the burn (thermal, electrical, chemical)

- Severity of the burn and total body surface area affected

- Procedure being performed

- Resuscitation status

- Organ dysfunction (renal, hepatic)

- Patient’s mental status

- Patient’s airway status

Pharmacological Options

Oral Nonsteroidal Anti-inflammatory Drugs (NSAIDs) and Acetaminophen

- Oral NSAIDs (ketorolac, ibuprofen, naproxen) and acetaminophen are commonly used for minor burns, usually in the outpatient setting. However, they exhibit a ceiling effect in their dose-response curve and are unsuitable as single agents for the treatment of severe burns.1,2

- NSAIDs and acetaminophen should be used as adjuncts for all patients in the absence of renal and hepatic dysfunction.4

Opioids

- Opioids are the cornerstone of pain management in burn patients.1,2,4

- Opioid requirements are significantly increased in burn patients and far exceed the standard dosing recommendations.

- Opioids can be administered orally, intravenously, or intranasally. Intramuscular opioid administration is not recommended in burn patients.

- Patient-controlled analgesia with intravenous opioids is a safe and effective method for managing pain in burn patients.1,2 For patients who are unable to press the button or are in severe pain, continuous background opioid infusions should be considered.

- Opioid therapy should be individualized to each patient and continuously adjusted throughout their care, taking into consideration individual patient responses and adverse effects.4

- Long-acting opioids, such as methadone, can be used if there is no concern for prolonged QT interval on electrocardiogram. Methadone should be considered in patients with opioid-induced hyperalgesia or as an adjunct to limit opioid administration in patients with difficult-to-control pain.5

Ketamine

- Ketamine should be considered for multimodal analgesia in burn patients who have likely developed a tolerance to opioids.1,2,4,5

- Due to an upregulation of N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptors in the spinal cord of burn patients, there is a resultant increase in ketamine requirement in burn patients.1,2

- In addition to analgesia, other favorable properties of ketamine include hemodynamic stability, preservation of respiration, bronchodilation, and anti-inflammatory effects.1,2

- Ketamine is especially useful for procedural sedation, including dressing or line changes, or if preservation of spontaneous ventilation is preferred.4

- Due to increased secretions associated with ketamine, glycopyrrolate coadministration should be considered.1,2 Administration of a benzodiazepine along with ketamine may also reduce the dysphoria.2

- Caution must be used because of catecholamine depletion in burn patients and the direct myocardial depressant effects of ketamine.

Dexmedetomidine

- Dexmedetomidine infusions can be used to provide sedation for minor procedures without producing the side effects seen with opioids, including itching and respiratory depression.2

- Dexmedetomidine infusions can also be used as a first-line sedative agent for intubated patients.4

- Dexmedetomidine is also useful as an adjunct for procedures in the operating room as an opioid-sparing strategy.

- As hypotension can be seen with infusions, dexmedetomidine should not be used in hemodynamically unstable patients.

Gabapentinoids

- Gabapentin and pregabalin should be used as adjuncts to opioids in patients with neuropathic pain and who are refractory to standard therapy.4

Anxiolytics

- Managing anxiety is an important part of pain management in burn patients.5

- Benzodiazepines are commonly used as adjuncts with opioids. Patients with increased procedural anxiety and high levels of pain are more likely to benefit from anxiolytic therapy.2

- Common side effects include sedation, dependence, and addiction.5

Antipsychotics and Antidepressants

- Antipsychotics (e.g., haloperidol and quetiapine) are increasingly being used for the management of anxiety and agitation in burn patients.2

- Antidepressants enhance opioid analgesia, especially in patients with neuropathic pain.2

Regional Anesthesia

- Regional anesthesia techniques should be considered to help ease the pain of both the burn site as well as the donor graft sites. The donor sites often have more pain than the primary burn site.1

- Regional anesthesia has the potential to improve pain relief, patient satisfaction, and opioid use reduction without serious risks or complications.4

- Regional anesthesia techniques include tumescent local anesthetic infiltration by the surgeon into the donor site prior to harvesting, single shot blocks, perineural catheters, or neuraxial techniques.1,2

- Common regional anesthesia blocks that can be performed in burn patients include:

- Lower extremity

- Femoral nerve block

- Adductor canal block

- Popliteal sciatic nerve block

- Upper extremity

- Brachial plexus blocks

- Lateral thigh

- Lateral femoral cutaneous nerve block

- Fascia iliaca block

- Abdominal wall

- Transverse abdominis plane block

- Quadratus lumborum block

- Rectus sheath block

- Large thoracic and abdominal burns

- Truncal blocks

- Lower extremity

Nonpharmacological Approaches

- Hypnosis, cognitive behavioral techniques, and distraction approaches have been used effectively to manage pain in burn patients.2,4,5

- Relaxation techniques, such as mindful meditation, deep breathing, and guided imagery, have also been shown to be beneficial.

- Early introduction of these multidisciplinary techniques may reduce overall anxiety and pain in burn patients.2

References

- Bittner EA, Shank E, Woodson L, et al. Acute and perioperative care of the burn-injured patient. Anesthesiology 2015; 122(2):448–64. PubMed

- Griggs C, Goverman J, Bittner EA, et al. Sedation and pain management in burn patients. Clin Plast Surg. 2017;44(3):535-40. PubMed

- Patterson DR, Sharar SR. Burn pain. In: Fishman SM, Balantyne JC, Rathmell JP (eds) Bonica’s Management of Pain, 4th edition. Philadelphia, PA. Lippincott Williams and Wilkins, 2010. 754.

- Romanowski KS, Carson J, Pape K, et al. American Burn Association guidelines on the management of acute pain in the adult burn patient: A review of the literature, a compilation of expert opinion, and next steps. J Burn Care Res. 2020:41(6):1129-51. PubMed

- Wiechman S, Bhalla P. Management of burn wound pain and itching. In: Post T (ed). UptoDate. 2023. Link

Copyright Information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.