Copy link

Aortic Insufficiency: Hemodynamic Management, Medical and Surgical Management

Last updated: 01/03/2023

Key Points

- Acute aortic insufficiency (AI) frequently leads to severe heart failure and warrants urgent diagnosis and intervention. Chronic AI is typically well tolerated due to left ventricular (LV) remodeling and adaptation.

- The definitive treatment of AI includes surgical intervention with aortic valve repair or replacement.

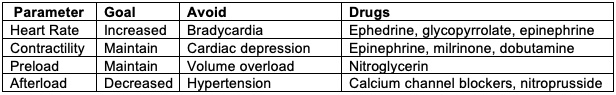

- The hemodynamic goals in a patient with AI include maintaining an elevated heart rate, adequate preload and contractility, and decreased afterload. Bradycardia must be avoided.

Hemodynamic Goals

- Acute severe AI is poorly tolerated, while chronic AI is typically well tolerated but may lead to systolic heart failure over time.

- Heart rate should be maintained between 80 to 100 bpm to decrease diastolic regurgitant time. Bradycardia should be avoided and treated with ephedrine, glycopyrrolate, or low-dose epinephrine.

- Contractility should be maintained to ensure adequate cardiac output. Low-dose epinephrine and inodilators are preferred (i.e., milrinone, dobutamine).

- Preload should be maintained to avoid both volume overload and decreased cardiac output. Volume overload may be treated with intravenous nitroglycerin.

- Afterload should be decreased to promote forward flow and augment cardiac output. Ensure adequate anesthetic depth and analgesia, and treat hypertension with vasodilators as necessary (i.e., calcium channel blockers, nitroprusside).

Table 1. Perioperative hemodynamic goals in patients with aortic regurgitation. Adapted from Mittnacht AJ, et al. Semin Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2008.1

Medical and Surgical Treatment

Medical Therapy

- For asymptomatic patients with chronic AI, treatment of hypertension (systolic blood pressure > 140 mm Hg) is recommended.2

- Patients with symptomatic severe AI and left ventricular (LV) systolic dysfunction who cannot have surgery should be started on guideline-directed medical therapy (GDMT), including ACE inhibitors and angiotensin II receptor blockers (ARBs).

- In acute AI, the goal is increasing the stroke volume and heart rate and decreasing the regurgitant fraction with afterload reduction.

- Beta-blockers are typically avoided in AI since their reduction in heart rate and negative inotropy can worsen AI.

- Intra-aortic balloon pumps are contraindicated in AI as they increase the severity of regurgitation.

- LV assist devices are also of limited utility in the setting of AI due to regurgitation leading to increased volumes in the LV and recirculation.

Surgical Treatment

- Definitive treatment of both acute and chronic AI is surgical intervention, with either aortic valve repair or replacement depending on the mechanism of AI.

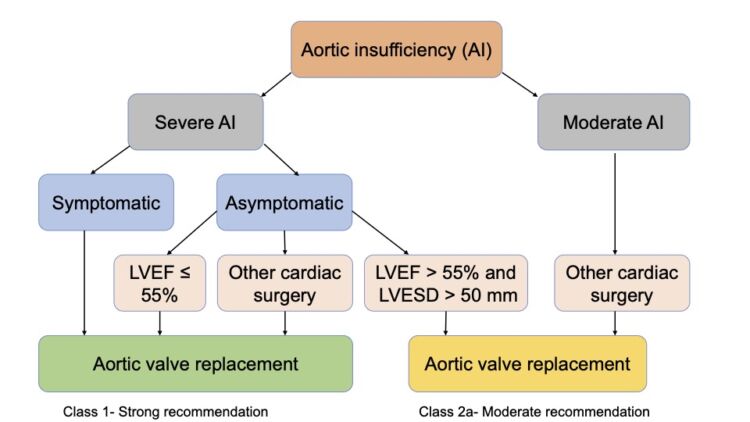

- In patients with moderate AR who are undergoing cardiac or aortic surgery for other indications, aortic valve surgery is reasonable.2 (Figure 1)

- In patients with severe AR who are symptomatic, aortic valve surgery is indicated regardless of the LV systolic function.

- In patients with severe AR who are asymptomatic, aortic valve surgery is indicated if the LV ejection fraction (EF) is less than 55% or if the patient is undergoing cardiac surgery for other indications. If the LVEF is greater than 55%, aortic valve surgery is reasonable when the LV is severely enlarged (LV end-systolic dimension is greater than 50 mm).

- In patients with asymptomatic severe AI and progressively decreasing LVEF less than 55%-60% or an increasing LV end-diastolic dimension greater than 65mm on three repeat studies, aortic valve surgery could be considered if there is low overall surgical risk; however, the usefulness remains less clear in this scenario.

Figure 1. Indications for surgical intervention in patients with AI. Adapted from Otto CM, et al. Circulation. 2021.2

Perioperative Considerations

- Patients with AI are at an increased risk of ischemia due to decreased diastolic coronary perfusion pressure and increased myocardial oxygen demand from increased wall tension.

- In addition to standard American Society of Anesthesiologists monitors, continuous invasive arterial blood pressure monitoring and placement of pulmonary arterial catheters should be considered in patients with severe AI.

- A preinduction arterial line placement should be considered.1

- For noncardiac surgery, general, regional, or neuraxial anesthesia may be used. Increased venous capacitance with a neuraxial block can decrease preload and cardiac output.

- Phenylephrine must be used with caution and a mixed agonist such as ephedrine might be a better choice.

- Atropine or glycopyrrolate may be used for the treatment of bradycardia.

- During cardiac surgery, retrograde cardioplegia or direct antegrade cardioplegia must be administered for myocardial protection as antegrade cardioplegia administered in the aortic root is ineffective.3

See Also

Aortic Insufficiency: Etiology, Pathophysiology, and Clinical Presentation

References

- Mittnacht AJ, Fanshawe M, Konstadt S. Anesthetic considerations in the patient with valvular heart disease undergoing noncardiac surgery. Semin Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2008;12(1):33-59. PubMed

- Otto CM, Nishimura RA, Bonow RO, et al. 2020 ACC/AHA guidelines for the management of patients with valvular heart disease: A report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Joint committee on clinical practice guidelines. Circulation. 2021;143(5):e72-e227. PubMed

- Voit J, Otto CM, Burke CR. Acute native aortic regurgitation: clinical presentation, diagnosis, and management. Heart. 2022; 108(20):1651-60. PubMed

Copyright Information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.