Copy link

Laryngospasm

Last updated: 01/13/2023

Key Points

- Laryngospasm is a physiological exaggeration of the protective glottic closure reflex, but can be life-threatening, resulting in hypoxia, bradycardia, and even cardiac arrest.

- Early recognition and prompt treatment are crucial and include applying continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) with 100% oxygen via a tight-fitting face mask, vigorous jaw thrust, and removing the offending stimulus.

- Succinylcholine is effective for the prompt treatment of laryngospasm.

Introduction

- Laryngospasm is a potentially life-threatening complication causing hypoxia and bradycardia that typically occurs in patients during induction and emergence from general anesthesia.1-3

- Other less common causes are gastroesophageal reflux, severe hypocalcemia, vitamin D deficiency, and Parkinson’s disease.

Pathophysiology

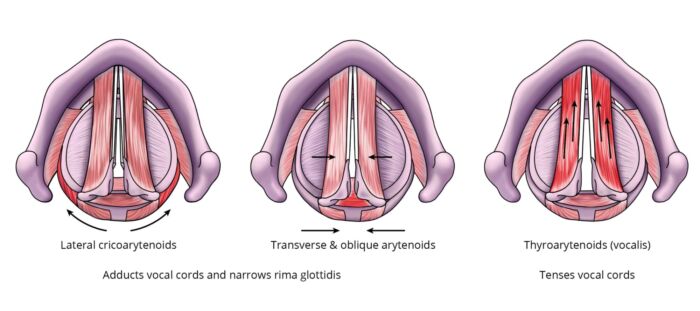

- Laryngospasm is a physiological exaggeration of the protective glottic closure reflex that is characterized by sustained closure of the true and false vocal cords and redundant supraglottic tissue (Figure 1).1-3

- Sensory input is via the internal branch of the superior laryngeal nerve and motor response is via the intrinsic laryngeal muscles and is mediated by the recurrent laryngeal nerve.3

Figure 1. Intrinsic muscles of the larynx involved in laryngospasm. Specific muscles are highlighted in red. The lateral cricoarytenoids, transverse, and oblique arytenoids adduct the vocal cords and close the glottic opening. The vocalis muscles are considered part of the thyroarytenoids, and they tense the vocal cords.

Clinical Presentation

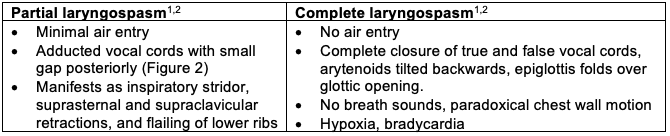

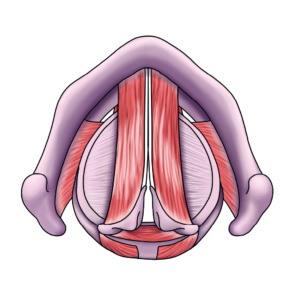

Table 1. Partial vs. complete laryngospasm. If left untreated or if the stimulation at a light depth of anesthesia continues, partial laryngospasm can turn into complete laryngospasm.

Figure 2. Partial laryngospasm with adducted vocal cords a small gap posteriorly.

Risk Factors

A combination of anesthesia, patient, and surgery-related risk factors increase the risk of laryngospasm.2,3

Anesthesia-Related Risk Factors

- Stimulation at a light depth of general anesthesia (laryngoscopy, extubation, blood or secretions irritating vocal cords)

- Volatile anesthetics (desflurane > isoflurane > halothane = sevoflurane)

- Multiple attempts at supraglottic airway insertion or direct laryngoscopy in patients in the lighter planes of anesthesia

- Inexperienced anesthesia provider

Patient-Related Risk Factors

- Age – Infants and young children are at greatest risk

- Asthma – up to 10-fold increased risk with active asthma

- Recent upper respiratory infection (up to 6 weeks) – up to 10-fold increased risk

- Second-hand smoke exposure – up to 10-fold increased risk in children

- Gastroesophageal reflux, obstructive sleep apnea

- Airway anomalies: subglottic stenosis, laryngeal papilloma, cleft palate, vocal cord paralysis, laryngomalacia, tracheal stenosis

Surgery-Related Risk Factors

- Shared airway: tonsillectomy and adenoidectomy (> 20% incidence), bronchoscopy

- Thyroid surgery: from superior laryngeal nerve injury or hypocalcemia

- Esophageal endoscopy: stimulation of distal afferent esophageal nerves

- Others: appendectomy, hypospadias repair, skin grafting, cervical dilatation

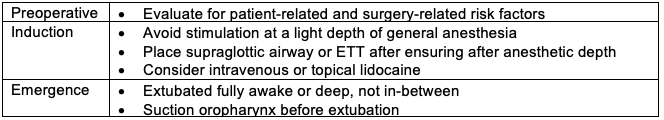

Prevention

Table 2.

Management

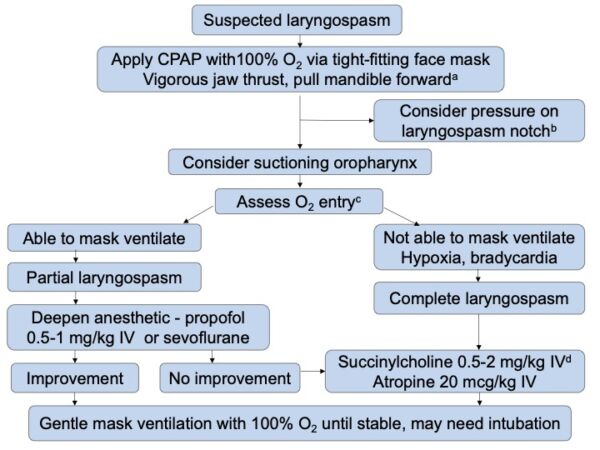

After ruling out other causes of airway obstruction, if laryngospasm is suspected, a clear plan of action and good communication is critical for improving patient outcomes (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Management of laryngospasm

- A vigorous jaw thrust lifts the epiglottis off the glottic opening, rocks the larynx forward, creates a gap between the vocal cords, and stimulates the patient since its very painful.

- Also known as Larson’s maneuver, this involves bilateral firm digital pressure on the styloid process behind the posterior ramus of the mandible. NEJM Video.

- Avoid vigorous attempts to mask ventilate as it may cause stomach insufflation.

- Consider succinylcholine 3-4 mg/kg IM if no IV access is present.

References

- Hampson-Evans D, Morgan P, Farrar M. Pediatric laryngospasm. Pediatr Anaesth. 2008:18:303-7. PubMed

- Alalami AA, Ayoub CM, Baraka AS. Laryngospasm: review of different prevention and treatment modalities. Pediatr Anaesth. 2008:18:281-88. PubMed

- Gavel G, Walker RWM. Laryngospasm in anaesthesia. Continuing Education in Anaesthesia Critical Care & Pain. 2014;14(2): 47-51. Link

- Holzki J, Laschat M. Laryngospasm. Paediatr Anaesth. 2008;18(11):1144-6. PubMed

Other References

- Chatterjee D. Laryngospasm. OpenAnesthesia. Published October 2017. Accessed January 13, 2023. Laryngospasm

- Whitten C. The Airway Jedi. 2014. Accessed March 24th, 2022. Link

- Whiten C. Laryngospasm. Accessed March 24th, 2022. Link

Copyright Information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.