Copy link

Venovenous Bypass During Liver Transplantation

Last updated: 02/21/2023

Key Points

- Venovenous bypass (VVB) allows for greater hemodynamic stability and decompression of the splanchnic circulation in patients undergoing liver transplantation (LT).

- In the early days of LT, VVB was extensively used for the classic liver transplantation (cLT) approach, but as the piggy-back LT (pbLT) technique has developed, the use of VVB has fallen away. Even so, some surgical programs routinely use VVB.

- There are no studies reporting better overall outcomes with the use of VVB.

Introduction

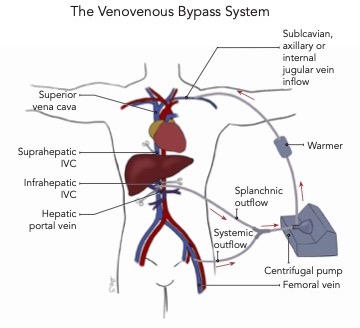

- VVB in LT is the process during which blood is diverted from major vessels below the level of the liver and returned to a vein above the level of the heart via an extracorporeal circuit and pump.

- VVB is undertaken during the hepatectomy stage of LT to mitigate the adverse hemodynamic effects related to the surgical clamping of the inferior vena cava (IVC) and portal vein (PV).

- Although the need for bypass was recognized by Starzl in the 1960s, the first successful use of VVB by Shaw was not until 1984.

- Improvements in anesthesia and surgical techniques have rendered the use of VVB in LT controversial.

Technique1-3

Catheter Placement

- Systemic bypass is the drainage, via a cannula, of the patient’s blood from below the level of the infrahepatic IVC, and its return to the venous system above the heart through a bypass circuit and pump (Figures 1).

- Portal bypass is the drainage of the splanchnic system and its diversion to the systemic bypass circuit.

- Both require the placement of high-volume, low-pressure inflow and outflow catheters. The femoral vein is frequently used to capture the systemic outflow, and the PV or superior mesenteric vein (SMV) is used for the portal outflow. The inflow catheter is usually placed in the axillary, subclavian, or internal jugular veins (Figures 1 and 2).

- Catheter access is percutaneous or through surgical cutdown. Percutaneous internal jugular venous catheters are often placed by the anesthesiologist.

Figure 1. The venovenous bypass (VVB) circuit

Figure 2. Blood outflow and return in VVB. Blood from the femoral vein is drawn into the bypass circuit (cannula A), where it is warmed before returning to the patient via the subclavian vein (cannula B). Image courtesy: Jennifer Cutler, MD.

Bypass Circuit

- The circuit consists of the heparin-bonded access catheters, a nonheparinized circuit, a centrifugal pump, and blood warmer.

- Bypass tubing connects the patient to the bypass pump.

- A perfusionist is required to operate the bypass machine.

- There are options for extra oxygenation and renal support

Figure 3. The bypass machine showing the centrifugal pump and blood warmer. Image courtesy: Jennifer Cutler, MD.

Indications and Contraindications2,3

- The choice to use VVB is based on the preferences and experience of the transplant surgical and anesthesiology teams.

- Indications to use or avoid the use of VVB are all relative.

- During the hepatectomy phase:

- Decompression of varices in patients with severe portal hypertension can be beneficial to optimize surgical conditions, diminish surgical bleeding and reduce the need for transfusion.

- The portal bypass after PV clamping will reduce splanchnic congestion and intestinal edema, thus improving gut perfusion and minimizing gut bacteria translocation.

- During the anhepatic phase:

- Cross-clamping the IVC decreases the cardiac output by up to 50%, which may not be tolerated by some patients. Returning bypass blood may help in the preservation of circulation hemodynamics. Test clamping the IVC may help in the decision to use VVB. If the hemodynamics (especially MAPs) cannot be maintained adequately, then VVB may be useful.

- In pbLT, where some IVC flow is preserved, surgeons may employ a temporary portosystemic shunt alone to decompress the splanchnic circulation.

- During reperfusion:

- Careful volume resuscitation is required, and VVB can provide more stability.

- Patients with portopulmonary hypertension are at risk of severe pulmonary hypertension and right heart failure if reperfusion occurs with excess cardiac preload.

- Patients in fulminant liver failure often present with intracranial hypertension and cerebral edema. Both conditions can worsen dramatically with uncontrolled hypo- or hypervolemia.

- The only absolute contraindication for VVB is its use in patients with acute Budd Chiari Syndrome, who have an increased risk of throwing off pulmonary emboli when placed on VVB.

- Complete portal vein occlusion due to thrombosis is a relative contraindication to VVB. For these patients, surgeons can opt to cannulate the mesenteric vein (superior or inferior) to decompress the splanchnic bed and/or use systemic bypass alone.

Benefits and Complications1-3

- VVB provides hemodynamic stability and allows for longer surgical time when the surgery is difficult.

- VVB has been linked to better outcomes for patients with existing renal disease by providing better kidney perfusion during PV clamping.4

- Complication rates from the use of VVB have been described as ranging from 10%-30%.

- With the use of percutaneous catheters, this risk has decreased, but complications still occur with the circuit and vascular access.

- Complications due to the circuit include:

- air/clot emboli occurring within the bypass circuit; and

- hemorrhage due to accidental disconnection from the bypass circuit.

- Complications due to vascular access include:

- seroma and lymphocele formation;

- wound infection;

- vessel damage and thrombosis;

- hemothorax;

- pneumothorax; and

- nerve injury.

References

- Lapisatepun W, Lapisatepun W, Agopian V, et al. Venovenous bypass during liver transplantation: A new look at an old technique. Transplant Proc. 2020;52(3):905-9. PubMed

- Reddy K, Mallett S, Peachey T. Venovenous bypass in orthotopic liver transplantation: time for a rethink? Liver Transpl. 2005;11(7):741-9. PubMed

- Fonouni H, Mehrabi A, Soleimani M, et al. The need for venovenous bypass in liver transplantation. HPB (Oxford). 2008;10(3):196-203. PubMed

- Sun K, Hong F, Wang Y, et al. Venovenous bypass is associated with a lower incidence of acute kidney injury after liver transplantation in patients with compromised pretransplant renal function. Anesth Analg. 2017;125(5):1463-70. PubMed

- Chari RS, Gan TJ, Robertson KM, et al. Venovenous bypass in adult orthotopic liver transplantation: routine or selective use? J Am Coll Surg. 1998;186(6):683-90. PubMed

Copyright Information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.