Copy link

Treacher Collins Syndrome

Last updated: 02/16/2023

Key Points

- Treacher Collins syndrome (TCS) is a congenital disorder characterized by distinctive craniofacial malformations that can lead to both difficult mask ventilation and laryngoscopy, requiring specialized intubation techniques.

- Direct laryngoscopy becomes more difficult with increasing age secondary to dysmorphic facial growth.

- A supraglottic airway usually works well as a rescue airway management strategy.

Introduction

- TCS, also called mandibulofacial dysostosis or zygotemporoauromandibular dysplasia, is a congenital disorder characterized by a constellation of several craniofacial malformations.1

- It is named after the British ophthalmologist Edward Treacher Collins.

- TCS is an autosomal-dominant disorder with variable penetrance and no gender predilection. The incidence of TCS is estimated at 1 in 50,000 live births.1

- About 60% of cases are spontaneous or de novo mutations, while 40% are family-specific mutations.

- The definitive method of diagnosis is genetic analysis, either prenatally or postnatally.

- TCS is a disorder of neural crest cell proliferation involving the development of the first and second branchial arches. Abnormalities are bilateral, symmetrical, and restricted to the head and neck.1,3

- TCS patients usually have normal cognition and intelligence.2

Clinical Presentation and Anatomical Characteristics

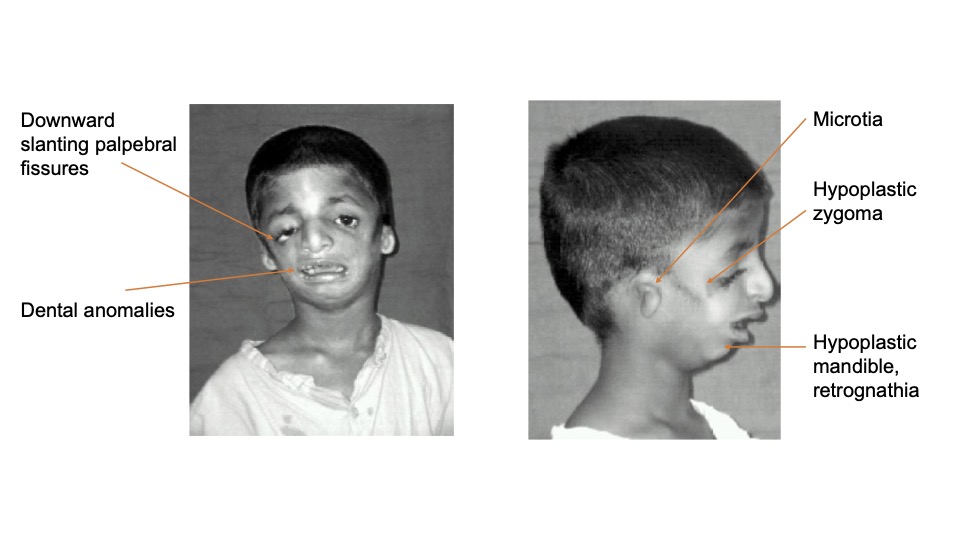

There is wide variability in the phenotypical presentation and the severity of facial dysmorphism in TCS patients (Figure 1).1,2

Eyes

- Periorbital anomalies (lateral orbital wall hypoplasia/aplasia contributing to canthal malposition, downward slanting palpebral fissures, canthal dystopia), colobomata of lower eyelids and iris, ectropion, absence of eyelashes in the medial aspect of the lid

- Lacrimal system dysfunction or aplasia with resultant epiphora

- Strabismus

- Amblyopia

- Congenital cataracts

- Refractive errors and/or vision loss

Ears

- Microtia with associated conductive hearing loss (can result in speech delay)

- Sometimes anotia (absence of external ears)

- External auricular deformity is commonly associated with a stenotic or atretic external auditory meatus and a malformed or absent middle ear.1

Midface

- Hypoplastic zygomas

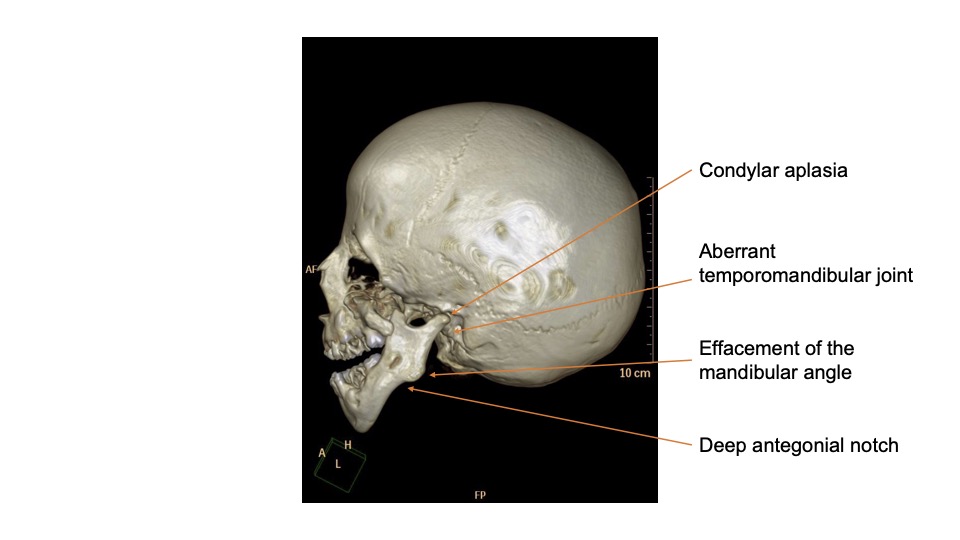

- Mandible: presence of Pierre Robin sequence (PRS) triad (TCS hence falls into the category of syndromic PRS) – micrognathia, glossoptosis, airway obstruction – because of pronounced retrognathia (posteriorly displaced mandible in relation to the upper jaw). The mandible, however, is not only hypoplastic but also malformed (Figure 2). Note the contrast to syndromes with predominantly micrognathic facies such as Pierre Robin and Cri du chat.2

Associated Anomalies

- Cleft palate (in 40% of cases)1

- Dental anomalies and malocclusion2

- Choanal atresia2

- Intellectual disability and other extra-facial anomalies (e.g., cardiac malformations) have been reported in the context of the underlying genetic mutation but are rare.2

- Obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) is often present and results from multilevel airway obstruction.1

Figure 1. TCS front and side views. Source: Goel L, et al. Treacher-collins syndrome-a challenge for anaesthesiologists. Indian J Anaesth. 2009;53(4):496-500. CC BY 3.0. Link

Figure 2. Treacher Collins 3D bone window image. Source: Ibrahim, D. Treacher Collins syndrome. Case study, Radiopaedia.org. Link

Medical Management

- The management of patients with TCS requires a multidisciplinary team approach.

Initial management of the neonate with TCS is focused on maintaining airway patency, ability to feed, and establishing the presence and etiology of obstructive sleep apnea.2- Those responding to prone or lateral positions with or without a nasal airway may be amenable to outpatient management since mandibular growth can be expected.

- Those needing oxygen therapy and positive pressure ventilation with or without intubation should be considered for further evaluation with polysomnography, sleep endoscopy, and microdirect laryngoscopy. These patients have a high risk of needing an early tracheostomy.

- Ongoing assessment and therapy are critical to address feeding difficulties, speech and language development.

- Salivary gland pathology results in oral dryness, and these patients have a higher prevalence of dental caries requiring early and continued dental care.1

- Ongoing eye care is often needed.

Surgical Management

- Priority is given to functional issues over aesthetics.

- The goals of airway procedures are:1

- improvement of OSA, preferably by avoidance of tracheostomy, by performing mandibular distraction osteogenesis (MDO), and tongue–lip adhesion;

- if tracheostomy is unavoidable, achievement of decannulation by creating space (adenoidectomy, tonsillectomy); and

- diagnosis and correction of associated airway anomalies such as laryngotracheomalacia, subglottic stenosis, vocal cord paralysis, septal deviation, choanal atresia.

- Procedures to alleviate feeding difficulties are:1

- cleft palate repair;

- oronasal fistula repair (occurs more often after cleft palate repair in TCS patients than in non-TCS patients);1

- correction of malocclusion; and

- gastrostomy tube placement.

- Ophthalmological procedures to minimize the risk of corneal desiccation and scarring1

- Procedures to promote speech development, such as a bone-anchored hearing aid1

- Cosmetic interventions such as microtia repair and the building of zygomas with bone grafts may occur later in life.1

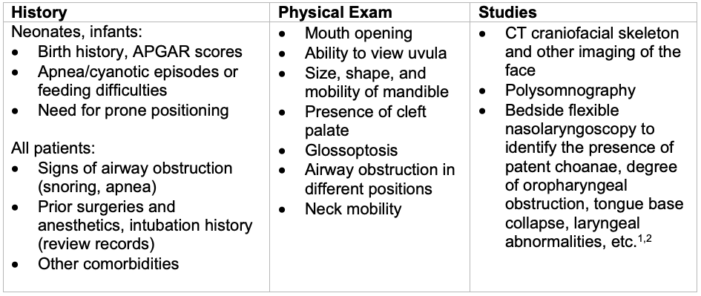

Anesthetic Considerations, Preparation and Management

- TCS patients are commonly scheduled for craniofacial surgery (33%), ENT surgery (21%), computed tomography (CT) scan (18%), dental (9%), and less commonly vascular access, general surgery, and neurosurgical procedures.3

- The main consideration for the anesthesiologist is the expectation of and preparation for difficult airway (DA) management. Many features of TCS are predictors of DA, including limited mouth opening, mandibular hypoplasia (contributing to reduced jaw protrusion), and OSA.4

- Direct laryngoscopy becomes more difficult with increasing age secondary to dysmorphic facial growth.4 This contrasts with children with Pierre Robin sequence who get easier to intubate as they grow older.

Table 1. Preoperative Evaluation

Preoperative Set-Uup

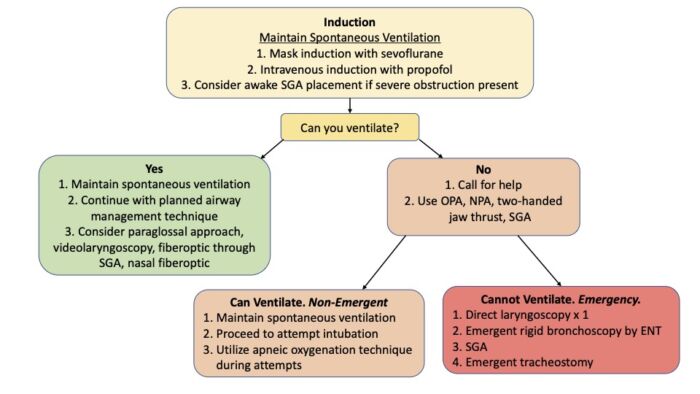

- Anticipate difficult mask ventilation due to multilevel upper airway obstruction

- Nasopharyngeal airways (NPA), oropharyngeal airways (OPA)

- Supraglottic airways (SGA)

- Two experienced providers for bag-mask ventilation

- Anticipate difficult direct laryngoscopic view

- Fiberoptic bronchoscope

- Videolaryngoscope

- SGA designed to facilitate tracheal intubation (“intubating SGA”)

- Anticipate cannot-intubate, cannot-ventilate scenario

- Discuss with ENT surgeons as appropriate

- Confirm the availability of an emergency tracheostomy kit

Intubation

- Apply the pediatric difficult airway algorithm (Figure 3).

- Administer supplemental oxygen throughout the intubation attempt

- Limit the number of intubation attempts

- Ensure eye protection during a possibly lengthy intubation process and throughout the surgical procedure

- Develop an extubation plan

Figure 3. Algorithm for airway management in patients with TCS. Abbreviations: OPA = oropharyngeal airway, NPA = nasopharyngeal airway, SGA = supraglottic airway. Adapted from Cladis F, et al. Pierre Robin sequence: a perioperative review. Anesth Analg. 2014;119(2):400-412. Same algorithm applied in Snyder H, Hunyady A. Pierre Robin sequence. OpenAnesthesia. Published January 12, 2023. Accessed February 16, 2023. Link

References

- Aljerian A, Gilardino MS. Treacher Collins syndrome. Clin Plastic Surg. 2019; 46:197–205. PubMed

- Chang CC, Steinbacher DM. Treacher Collins syndrome. Semin Plast Surg. 2012;26(2):83-90. PubMed

- Lerman J, Cote C, Steward D. Techniques and Procedures. In: Manual of Pediatric Anesthesia. Seventh Edition. Switzerland; Springer; 2016: 103-5.

- Hosking J, Zoanetti D, Carlyle A, et al. Anesthesia for Treacher Collins syndrome: a review of airway management in 240 pediatric cases. Paediatr Anaesth. 2012;22(8):752-8. PubMed

Copyright Information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.