Copy link

Substance Use Disorder in Pregnancy

Last updated: 09/25/2025

Key Points

- Substance use disorder (SUD) in pregnancy is common and underreported, with rising rates of opioid use disorder (OUD). Universal screening at the first prenatal visit using validated tools (e.g., 4Ps, CRAFFT, NIDA Quick Screen) is essential to avoid missed diagnoses and reduce stigma.

- Medication for opioid use disorder with methadone or buprenorphine is the standard of care for OUD during pregnancy and should be continued through labor and postpartum.

- Neuraxial and regional anesthesia are preferred due to opioid tolerance and the need for multimodal pain control strategies that minimize relapse risk.

- Regional techniques, such as the transversus abdominis plane (TAP), quadratus lumborum (QL), and erector spinae plane (ESP) blocks, offer safe and effective adjuncts or alternatives for cesarean delivery pain management, particularly when neuraxial opioids are not used.

Introduction

- According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, overdose is one of the leading contributors to maternal mortality in the United States.

- SUD in pregnancy is a chronic, relapsing condition with potential harm to both mother and fetus.

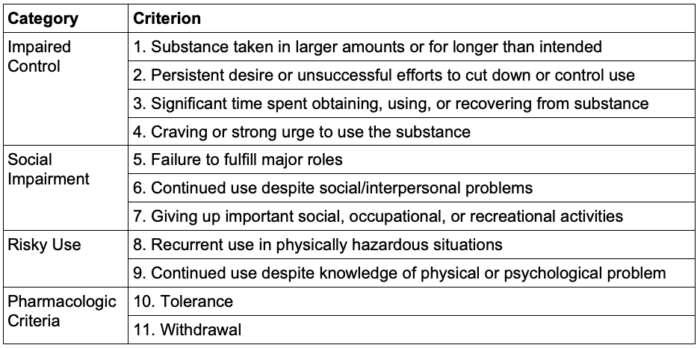

- Per the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th edition (DSM-5), a diagnosis of SUD requires at least 2 of the following symptoms in 12 months:1

- Severity

- Mild: 2–3 criteria

- Moderate: 4–5 criteria

- Severe: 6 or more criteria

- Severity

DSM-5 Criteria for SUD

Table 1. DSM-5 Criteria for substance use disorder

- SUD in pregnancy is often underreported because of stigma, fear of legal repercussions, or losing child custody.

- The rate of OUD in parturients rose by 131% from 2010 to 2017.2

- Screening for SUD should be performed universally, starting at the first prenatal visit. Relying only on risk factors such as inconsistent prenatal care or a history of adverse pregnancy outcomes can lead to missed diagnoses and increase bias and stigma.

- To ensure equitable and effective identification, routine screening should use validated tools, such as the 4Ps, NIDA Quick Screen, and CRAFFT (for patients 26 years or younger).3

Substance Use Disorders

OUD

- For pregnant individuals with OUD, treatment with opioid agonist therapy is recommended, as it is associated with better outcomes compared to medically supervised withdrawal.3

- Withdrawal during pregnancy carries a high risk of relapse, which can result in adverse maternal and fetal outcomes. While medically supervised withdrawal may be considered in select cases, further research is needed to evaluate its safety.3

- Obstetric Complications

- Opioid use increases the risk of preterm birth, low birth weight, and maternal complications, especially when accompanied by poor prenatal care or polysubstance use.

- Neonatal abstinence syndrome: Chronic opioid use during pregnancy can lead to postnatal withdrawal in the newborn. Symptoms can include irritability, feeding difficulties, and seizures.

- Medication for Opioid Use Disorder

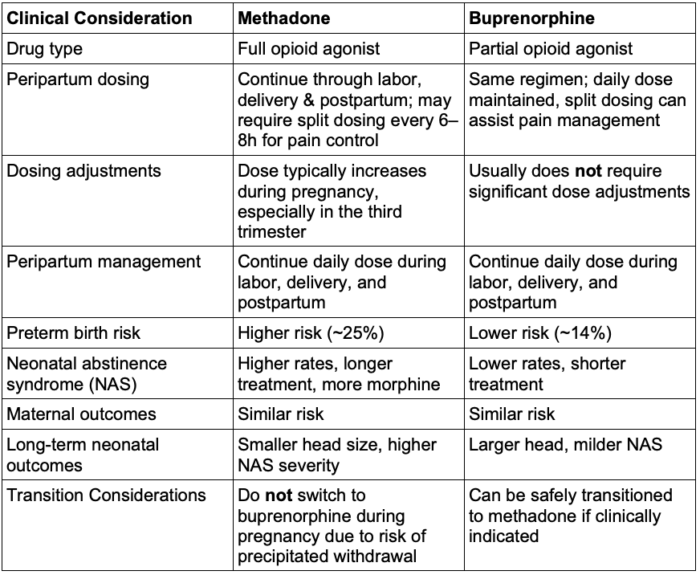

- Methadone and buprenorphine are both commonly used treatments for OUD.

- The patient’s daily dose should be continued through labor & delivery as well as postpartum to avoid the risk of withdrawal.3

- Buprenorphine is associated with a lower risk of adverse fetal outcomes, though the risk of adverse maternal outcomes is the same between buprenorphine and methadone.4

- If a pregnant individual is already being treated with methadone, switching to buprenorphine is not recommended due to the high risk of precipitated withdrawal. In contrast, transitioning from buprenorphine to methadone does not carry the same risk and can be done more safely if clinically indicated.3

- If the patient is taking opioid agonist therapy, opioid antagonists such as nalbuphine or butorphanol should be avoided.

Comparison of Methadone vs Buprenorphine in Pregnancy

Table 2. Comparison of methadone vs buprenorphine in pregnancy

- Pain management can be challenging, especially in patients with OUD, due to tolerance and hyperalgesia.

- Patients taking methadone or buprenorphine will require a higher dose of opioid for sufficient analgesia.

- Management of acute withdrawal

- Promptly evaluate signs of opioid withdrawal (e.g., agitation, sweating, tachycardia, nausea). Stabilize maternal vital signs and provide supportive care, including intravenous fluids, oxygen, and symptomatic treatment as needed.

- Maintain or reinstate methadone or buprenorphine dosing to prevent worsening withdrawal symptoms. Avoid abrupt discontinuation of opioid agonists during labor.

- Use non-opioid adjuncts such as clonidine or antiemetics cautiously to control withdrawal symptoms.

- Neuraxial analgesia is preferred and effective for labor pain. Consider multimodal analgesia while monitoring closely for increased opioid tolerance.

- Prepare for possible neonatal abstinence syndrome. Notify pediatric/neonatal teams early for post-delivery monitoring and support.

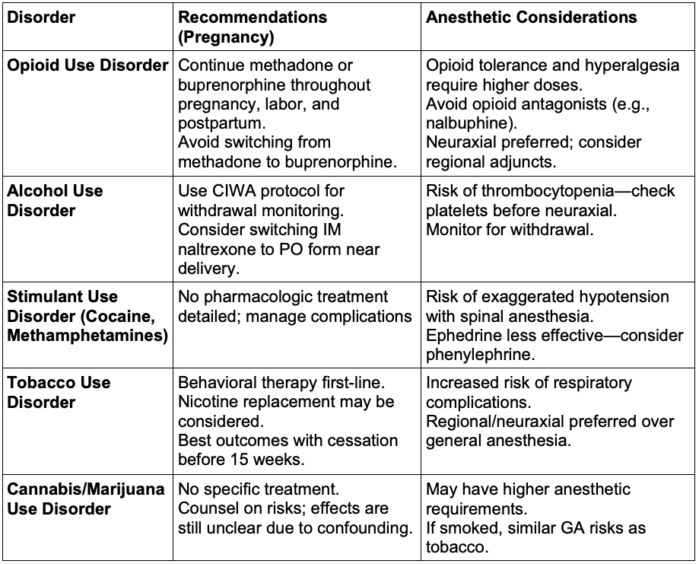

Alcohol Use Disorder (AUD)

- In the United States, 8.4% of pregnant people ages 15 to 44 have used alcohol in the past month.5

- The management of patients with AUD partially depends on whether they are acutely intoxicated or taking pharmacologic therapy.

- Acute intoxication: Patients who are acutely intoxicated may be at risk of withdrawal over their labor course. Patients should be placed on a monitoring protocol, such as the Clinical Institute Withdrawal Assessment protocol, to look out for symptoms of withdrawal.

- Patients who have a history of AUD may be prescribed naltrexone as part of their treatment.6

- As patients taking IM naltrexone near the delivery date, a discussion should be had about switching to the PO formulation, as it has a shorter half-life. It may interfere less with intrapartum pain management.

- Chronic alcohol use can be associated with thrombocytopenia and should be evaluated prior to neuraxial placement.

Stimulant Use Disorder (Cocaine, Methamphetamine)

- Cocaine and amphetamines increase maternal sympathetic activity by inhibiting the reuptake of neurotransmitters. In patients using these stimulants, intrathecal local anesthetics can cause a pronounced sympathectomy and lead to significant hypotension.7

- Chronic use often results in catecholamine depletion, rendering ephedrine less effective for treating hypotension.

- Obstetric complications

- Cocaine use increases the risk of placental abruption.

- Cocaine is associated with intrauterine growth restriction, preterm birth, and neurodevelopmental delays due to its vasoconstrictive effects and interference with oxygen and nutrient delivery to the fetus.

Tobacco Use Disorder

- The greatest benefit of smoking cessation is seen when the patient quits before 15 weeks’ gestation.

- From an anesthetic perspective, the primary concern is an increased risk of respiratory complications, such as reactive airway disease and bronchospasm. Since obstetric anesthesia typically relies on regional or neuraxial techniques, the risks of airway manipulation and respiratory complications are minimized.7

- However, when general anesthesia is necessary, airway management and postoperative respiratory monitoring require heightened attention.

- Behavioral therapy is the first-line treatment. Nicotine replacement can also be considered.

- Obstetric Complications

- Tobacco use in pregnancy is associated with a myriad of complications, including placental abruption, placenta previa, fetal growth restriction, preterm premature rupture of membranes, and increased perinatal mortality.

Cannabis/Marijuana Use Disorder

- There may be an association between marijuana use in pregnancy and low birth weight and an increased risk of stillbirth. The exact effects are still uncertain due to the prevalence of confounding variables in studies.8

- If the primary route of use is smoking, the risks of general anesthesia are similar to those detailed above.

- Patients with marijuana use disorder may exhibit higher anesthetic requirements.

Table 3. Review of substance use disorder in pregnancy. Abbreviations: CIWA, Clinical Institute Withdrawal Assessment; IM, intramuscular; PO, per os; GA, general anesthesia

Anesthetic Considerations

- Neuraxial and regional anesthesia are preferred in patients with SUD because they provide effective pain control while minimizing the need for systemic opioids.

- Patients may benefit from a consultation with the anesthesiologists before delivery to formulate a pain management plan that aligns with their personal goals. For example, some patients with OUD may wish to avoid opioids altogether in their labor course.

Neuraxial

- Neuraxial anesthesia is the mainstay treatment for intrapartum pain management – whether an epidural for labor or neuraxial for cesarean delivery.

- The epidural may be continued into the postpartum period for ongoing pain management if clinically appropriate. In order to allow for ambulation, the anesthesia team can consider either a low thoracic epidural or an opioid-only infusion.

Regional

- In the event of general anesthesia and no neuraxial, regional anesthesia is a valuable pain management tool in patients with SUD.

- TAP blocks have demonstrated significant improvement in postoperative pain control for cesarean deliveries performed without neuraxial opioid administration.

- The additional benefit of a TAP block is lost when neuraxial morphine is also administered.9

- QL and ESP blocks have also been used to provide effective analgesia after cesarean delivery.

- TAP blocks have demonstrated significant improvement in postoperative pain control for cesarean deliveries performed without neuraxial opioid administration.

General

- If general anesthesia is required, depending on the substance and acuity of intoxication, patients may have altered anesthetic requirements.

- For example, patients who are acutely intoxicated with alcohol may have a lowered anesthetic requirement.

- Patients with OUD may require higher doses of opioids for adequate analgesia.

References

- American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.).

- Hirai AH, Ko JY, Owens PL, et al. Neonatal abstinence syndrome and maternal opioid-related diagnoses in the US, 2010-2017. JAMA. 2021;325(2):146-155. PubMed

- Committee Opinion No. 711: Opioid use and opioid use disorder in pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;130(2):e81-e94. PubMed

- Suarez EA, Huybrechts KF, Straub L, et al. Buprenorphine versus methadone for opioid use disorder in pregnancy. N Engl J Med. 2022;387(22):2033-2044. PubMed

- SAMHSA, Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality. 2023 National Survey on Drug Use and Health. Table 8.26B—Substance use in past month: among females aged 15 to 44; by pregnancy status, percentages, 2022 and 2023. Link

- Kelty E, Terplan M, Greenland M, Preen D. Pharmacotherapies for the treatment of alcohol use disorders during pregnancy: Time to reconsider? Drugs. 2021;81(7):739-748. PubMed

- Stahl DL, Matthews LJ. Caring for parturients with substance use disorders. Anesthesiol Clin. 2021;39(4):761-777. PubMed

- Committee Opinion No. 722: Marijuana use during pregnancy and lactation. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;130(4):e205-e209. PubMed

- Champaneria R, Shah L, Wilson MJ, Daniels JP. Clinical effectiveness of transversus abdominis plane (TAP) blocks for pain relief after caesarean section: a meta-analysis. Int J Obstet Anesth. 2016;28:45-60. PubMed

Other References

- Webinar: “The Management of Care for Pregnant Women with Opioid and Other Substance Use Disorders.” SAMHSA. Posted 2021. Accessed: September 25, 2025. Link

Copyright Information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.