Copy link

Stellate Ganglion Block

Last updated: 05/24/2024

Key Points

- The stellate ganglion (SG) is part of the cervical sympathetic trunk. A stellate ganglion block (SGB) is used for several chronic pain conditions, including complex regional pain syndrome (CRPS).

- Due to their sympathetic input to these regions, SGBs can be useful in the diagnosis and treatment of pain syndromes in the upper limb, head, and neck.

- The ultrasound-guided technique is widely utilized and the preferred method due to the safety it provides via the visualization of surrounding anatomical structures.

- A successful block is confirmed by the presence of transient ipsilateral Horner syndrome.

- Severe complications are rare. The most common side effect is hoarseness.

Introduction

- The SG, also known as the cervicothoracic sympathetic ganglion, is a part of the cervical sympathetic trunk. This “star-shaped” ganglion is formed by the fusion of the inferior cervical ganglia and the first thoracic ganglia.1,2 The SG is present in about 80% of the general population.2

- While anatomically imprecise, it is common practice to refer to the blockade of the cervical sympathetic trunk as an SGB. Given that only traversing sympathetic fibers or middle cervical ganglia can be found at the C6 level, this procedure should more accurately be called a cervical sympathetic block.3

- In an SGB, the local anesthetic is injected at the C6 or C7 vertebral level with the anterior tubercle of the transverse process of C6 (Chassaignac’s tubercle), the cricoid cartilage, and the carotid artery serving as the anatomic landmarks to the procedure.2 The injected local anesthetic travels inferiorly anesthetizing the sympathetic nerve fibers at the SG.

- The SG provides sympathetic inputs to the ipsilateral upper limbs, chest, face, and head. Therefore, SGBs can be useful in diagnosing and treating sympathetically mediated pain in the upper limb, head, and neck regions.2

- Although the exact mechanism remains unclear, the therapeutic mechanism in pain disorders may be mediated by improving the blood supply to the head and neck, inhibiting the hyperexcitability of sympathetic nerves, and reducing the synthesis and release of vasoconstricting substances, such as nitric oxide and prostaglandin.1

Anatomy

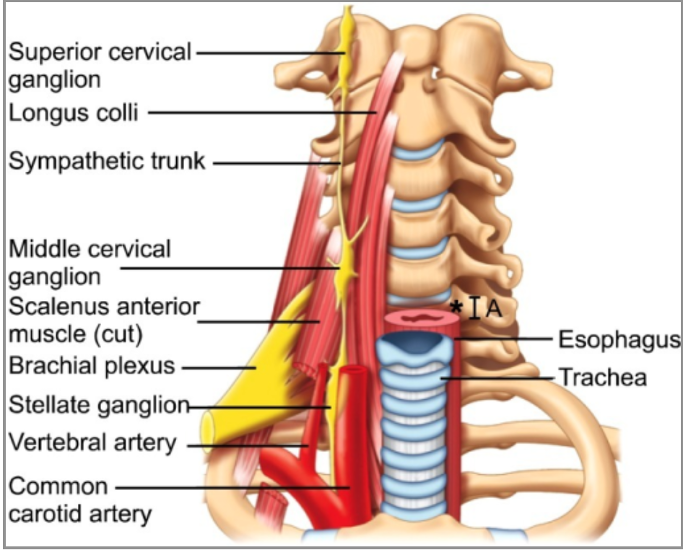

- The SG sits anterior to the neck of the first rib and extends upward to the inferior portion of the transverse process of C7. It is located on the anterior surface of the lateral border of the longus colli muscle (Figure 1).

- The SG lies posterior to the common carotid artery, anterior to the vertebral artery, and its inferior pole is located near the costocervical trunk of the subclavian artery.1,4 The ganglion is structurally separated from the posterior aspect of the cervical pleura by the suprapleural membrane.3 This explains the increased risk of pneumothorax and vertebral artery injury at the C7 level.

- The esophagus, recurrent laryngeal nerve, trachea, and vertebral column lie medially to the SG.

- The SG measures 1 to 2.5 cm in length, 1 cm wide, and 0.5 cm thick. It is referred to as the stellate ganglion due to its star shape, but can be fusiform, triangular, or globular.3

- Postganglionic fibers from this ganglion supply the C7, C8, and T1 nerve roots and the vertebral plexus.

Indications

- SGBs have been used successfully in the management of a variety of chronic pain syndromes, including CRPS type I and II, phantom limb pain, postherpetic neuralgia, migraine, facial pain syndromes, and postmastectomy pain syndromes.1,2

- In addition, this procedure can be useful for treating vascular insufficiency in the upper extremity such as vasculitis, Raynaud’s disease, obliterative arterial disease, inadvertent injection of an irritant drug, and postembolectomy vasospasm.1-3

- Other indications include chronic postsurgical pain, cancer pain, atypical chest pain, angina pectoris, and cluster or vascular headaches.1-3

- SGBs can also be used for the treatment of drug-refractory electrical storms due to ventricular arrhythmias.1,4

Techniques

- The feasibility and safety of SGB have greatly improved since the introduction of the ultrasound-guided technique. Therefore, ultrasound guidance has become the preferred method for SGB when compared to blind and fluoroscopic guidance.1 Medications used in SGB include bupivacaine, lidocaine, or mepivacaine, which are sometimes combined with a steroid medication depending on the physician’s preference.6

- Most commonly, a successful block is confirmed by the presence of a transient ipsilateral Horner’s syndrome (ptosis, miosis, and anhidrosis). These symptoms usually resolve in 4 to 6 hours after the injection. An increase in perfusion index and extremity temperature can also indicate a successful block.1,7

Landmark-Based Technique (using the C6 anterior approach)

- This technique is also termed the “blind” or paratracheal approach. The patient is placed in the supine position with a slight extension of the head. The head should be turned away from where the block will be performed.

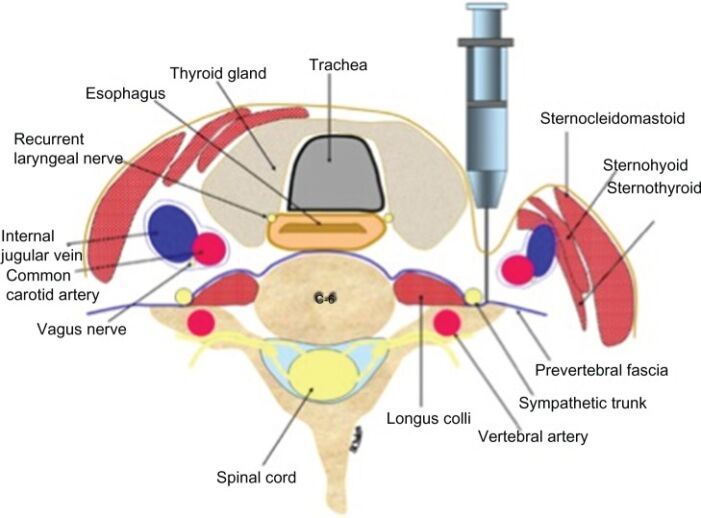

- After retracting the sternocleidomastoid muscle, carotid artery, jugular vein, and vagus nerve, the cricoid cartilage should be palpated to establish the C6 level. The anterior tubercle of the C6 transverse process (Chassaignac’s tubercle) can then be felt and used as a landmark to advance the needle.

- The needle is then inserted paratracheal until it contacts bone, presumably the lateral part of the vertebral body. The needle is then withdrawn 1 to 5 mm to withdraw from the longus colli muscle. After negative suction, a test dose of about 1 mL should be administered, and then the subsequent 8 to 10 mL of local anesthetic can be administered.7

Figure 2. Landmark-based technique for SGB using the C6 anterior approach, cross-section of relevant anatomy. Source: Amhaz HH, et al. Local and regional anesthesia. 2013. Link CC BY-NC 3.0 DEED.

Fluoroscopic Technique

- Fluoroscopy-guided SGB is often performed similar to the landmark-based technique described above but provides a better depiction of the bony anatomy.

- While the fluoroscopic technique may help to prevent complications related to intravascular, nerve root, or neuraxial injection, it does not provide visualization of the soft tissue, vessels, and cervical sympathetic ganglia.3 It involves the administration of contrast, which assures that the needle tip is in the appropriate fascial plane.7

- With the patient in a supine position, a C-arm is used to obtain an anteroposterior view to identify C6 by counting up from T1. The target is the junction of the vertebral body and the uncinate process of C6. Under an oblique view, the needle is inserted laterally and remains over the vertebral body to avoid injury to vessels, spinal nerves, and disc.2

- The position needs to be checked thoroughly using the anteroposterior and lateral views. A small amount of contrast media (0.5 to 1 mL) can be injected first to localize the needle.2 Due to the high concern for local anesthetic systemic toxicity (LAST) and seizures with intravascular administration, a test dose of lidocaine with epinephrine is administered.2 Then 10 mL of a local anesthetic is injected. This same procedure can be performed at C7, but there are higher risks of vascular puncture at this level.

Ultrasound guidance may prevent the complications and adverse outcomes associated with either blind or fluoroscopically guided techniques.

Ultrasound-Guided (C6 transverse) Technique:

- The carotid sheath and sternocleidomastoid muscles are retracted laterally using the ultrasound transducer. Gentle pressure is applied to reduce the distance between the skin and the tubercle.

- Under ultrasound guidance, the block needle is inserted towards the Chassaignac tubercle. After contacting the tubercle, the needle is withdrawn about 1 to 2 mm so that it is located in the area of the prevertebral fascia.

- The needle tip should be anterolateral to the longus colli muscle, deep to the prevertebral fascia (to avoid spread along the carotid sheath), but superficial to the fascia encasing the longus colli muscle.5 This facilitates the caudal spread of the local anesthetic to reach the stellate ganglion at the C7-T1 level.

- After negative aspiration, a small amount of local anesthetic is injected, and the subfascial spread of the anesthetic should be visualized using ultrasound.

- Once the visualization confirms subfascial drug deposition, the clinician can administer the remainder of the local anesthetic.5,7

Ultrasound-Guided (C7 anterior) Technique

- This method carries a slightly higher risk of pneumothorax and vertebral artery injury but provides a more consistent blockade as the needle lies closer to the ganglion.7 As a result, less local anesthetic can be used.

- This technique is particularly useful in cases of failed blocks at the C6 level.7

- The C7 approach always needs imaging as the C7 vertebrae have a vestigial tubercle which is not readily palpable.7

- As for all the techniques, an aspiration test must be done to avoid the suction of blood or cerebrospinal fluid, then the local anesthetic can be injected. The diffusion of the injectate is seen in real-time.

- Regardless of the technique used, a gross neurological exam should be performed following the procedure.

The fluoroscopic approach may be combined with ultrasound to confirm the intended level and further minimize the risk of complications. With fluoroscopy, the needle can be accurately directed to the anterior tubercle of the C6 transverse process. However, the location of the cervical sympathetic trunk is more accurately defined by the fascial plane of the prevertebral fascia, which cannot be visualized with fluoroscopy.5 In addition, vascular structures (such as the inferior thyroidal, cervical, vertebral, and carotid arteries) and soft tissue structures (such as the thyroid and esophagus) can be seen with ultrasound, but not with fluoroscopy. A combined imaging approach allows visualization of the bony anatomy while providing added safety via imaging of vascular and soft tissue structures.8

Adverse Effects and Complications

- Complications are rare with the use of image-guided techniques, but they can be significant due to the SG’s anatomical location near many vital structures.

- There is a higher risk for vascular puncture if the procedure is performed at C7 versus C6 level.

- SGBs are typically contraindicated in anticoagulated patients due to increased risk of hemorrhage and hematoma.6 Anticoagulation guidelines should be strictly adhered to while considering a SGB.

- Using the landmark-based approach can lead to unreliable results and severe complications, including hematoma caused by blood vessel injury, intravascular injection, esophageal injury, and recurrent laryngeal nerve injury.1,3 In a systematic review discussing complications of SGBs, the most commonly reported adverse event was hoarseness likely due to recurrent laryngeal nerve injury.6

- Injection of the local anesthetic into the wrong space, such as intravascularly, subdurally, or intrathecally, is associated with adverse events requiring mechanical ventilation and cardiopulmonary resuscitation due to the potential for LAST as well as high or total spinal block.6

- There have been case reports of pneumothorax secondary to SGB with the landmark-based approach.6,9

- It is important to note the contraindications to performing a stellate ganglion nerve block, such as recent history of a myocardial infarction, anticoagulated patients, coagulopathy, glaucoma, and patients with a preexisting cardiac conduction blockade.2

References

- Deng JJ, Zhang CL, Liu DW, et al. Treatment of stellate ganglion block in diseases: Its role and application prospect. World J Clin Cases. 2023;11(10):2160-2167. PubMed

- Piraccini E, Munakomi S, Chang KV. Stellate ganglion blocks. In: StatPearls (Internet). Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing. 2024. Link

- Gofeld M, Shankar H. Peripheral and visceral sympathetic blocks. In: Practical Management of Pain (Fifth Edition). Mosby. 2014:755-767. Link

- Tian Y, Wittwer ED, Kapa S, et al. Effective use of percutaneous stellate ganglion blockade in patients with electrical storm. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2019;12(9):e007118. PubMed

- Narouze S. Ultrasound-guided stellate ganglion block: Safety and efficacy. Curr Pain Headache Rep. 2014;18(6):424. PubMed

- Goel V, Patwardhan AM, Ibrahim M, et al. Complications associated with stellate ganglion nerve block: a systematic review. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2019. PubMed

- Mehrotra M, Reddy V, Singh P. Neuroanatomy, stellate ganglion. In: StatPearls (Internet). Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing. 2024. Link

- Shepherd J, Dua A, Martin D. (463) Dual imaging technique for stellate ganglion blockade. The Journal of Pain. 2016;17(4):s90. Link

- Karaman H. Complications and success rates of stellate ganglion blockade; blind technique vs fluoroscopic guidance. Biomed Res. 2017; 28:1677–82. Link

Other References

- Gadsden J. Ultrasound-guided stellate ganglion block. Duke Regional Anesthesiology and Acute Pain Medicine. Link

Copyright Information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.