Copy link

Spinal Anesthesia in Neonates and Infants

Last updated: 11/17/2023

Key Points

- Spinal anesthesia can be safely performed in patients from 0 days of age to childhood. Spinal anesthesia is particularly useful in patients at high risk for airway complications, postoperative apnea, or in healthy children undergoing elective procedures.

- Procedures ideal for spinal anesthesia are those in which the surgical site is below the xiphoid process and the expected surgical time is 90 minutes or less.

- Spinal anesthesia can be combined with an indwelling epidural catheter (e.g., threaded via caudal approach) for longer procedures when avoidance of general anesthesia is desired.

Introduction

- Spinal anesthesia in neonates, infants, and children reduces exposure to systemic anesthetics and opioids while providing excellent surgical conditions and maintaining respiratory and cardiovascular homeostasis.

- Examples of common surgeries performed under spinal anesthesia are lower extremity orthopedic procedures, spica casting, femoral central line placement, inguinal or umbilical hernia repair, orchiopexy, hypospadias repair, circumcision and open pyloromyotomy.1

- Patient selection typically includes infants younger than 6 months old and weighing less than 5 kg. However, it is not uncommon to use spinal anesthesia for infants up to 2 years old and less than 15 kg when avoidance of general anesthesia is desired.

- Patients should not have spinal pathology and should not be taking anticoagulants. Spinal anesthesia is safe in patients at risk of malignant hyperthermia or rhabdomyolysis from inhalational anesthetics.

- The Vermont Infant Spinal Registry consisted of 1554 patients undergoing spinal anesthesia with 95.4% success in spinal placement adequate for surgery. These patients ranged in weight from 540 g to 7800 g with a mean of 4379 g.2

- Of these 1554 patients, the following anesthetic-related complications were noted:

- Need for intravenous (IV) sedation (360 patients, 24%)

- Desaturation to less than 90% SpO2 (10 patients, 6%)

- 5 requiring mask ventilation and 5 requiring intubation.

- Heart rate less than 100 (24 patients, 1.6%)

- High spinal and bradycardia (3 patients, 0.2%)

- In comparative trials, these complications are lower in spinal anesthesia groups than general anesthesia groups.

- Spinal anesthesia reduces the incidence of intraoperative hypotension in infants. In a randomized clinical trial of 722 infants undergoing inguinal hernia repair via inhalational versus spinal anesthesia, hypotension defined as a mean arterial pressure less than 35 mmHg from baseline occurred more frequently in the inhalational group, with a relative risk of 2.8.3

Procedure

- Parents are often not familiar with infant spinal anesthesia and will need an informed consent discussion prior to proceeding. Standard fasting guidelines should be used in the event that general anesthesia is required.

- Eutectic mixture of local anesthesia (EMLA) or similar topical local anesthetic is placed on the patient’s back for at least 30 minutes prior to the procedure. The local anesthetic should be placed under an occlusive dressing (e.g. Tegaderm) to cover the L4-5, L5-S1 levels. This increases patient comfort and improves first-pass success rates.

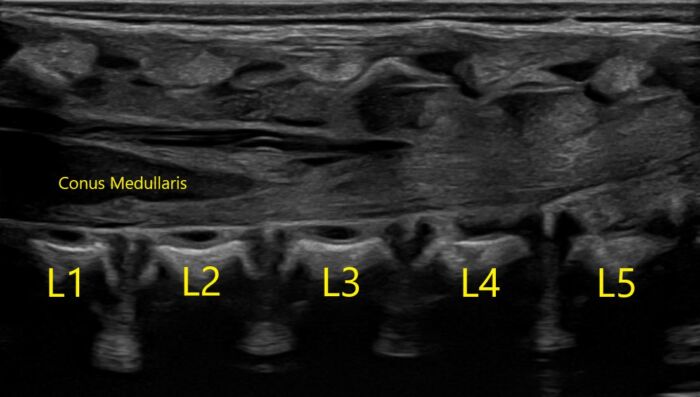

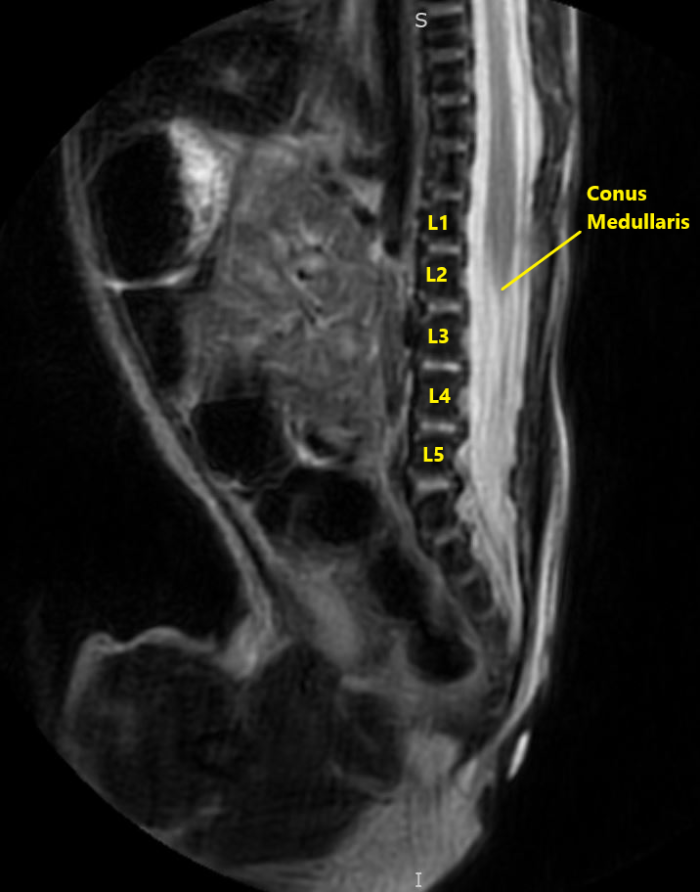

- Familiarity with infant neuraxial anatomy is crucial in placing a safe and effective block. The conus medullaris is further caudad than in adult anatomy. The infant conus medullaris is most commonly at the L2-L3 level (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Normal longitudinal ultrasound of a one-day-old infant of 39w5d gestation. Image courtesy of Timothy Higgins, MD, University of Vermont Department of Radiology.

Figure 2. Sagittal view of normal T2 MRI anatomy of the same infant. Image courtesy of Timothy Higgins, MD, University of Vermont Department of Radiology.

- If needed, oral midazolam 0.5 mg/kg or intranasal dexmedetomidine 3 mcg/kg may be necessary to sedate the patient for positioning and block placement. An IV catheter may be placed prior to block placement, but in most patients, it is not required. Unlike adults, spinal anesthesia in children less than 5 years of age is extremely unlikely to cause respiratory or cardiovascular instability. More commonly, the IV catheter is placed in a lower extremity once the spinal anesthetic begins to take effect.

- Patient positioning may be sitting or lateral. The sitting position is often preferred by anesthesiologists as identification of midline is often easier and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) return is usually faster once the intrathecal space is entered. An experienced assistant is crucial for optimal positioning of the patient in a sitting position with adequate lumbar vertebral flexion and neck stabilization to ensure airway patency.

- After sterile preparation, a midline approach is commonly used to obtain CSF at the L3-4, L4-5, or L5-S1 level. The most commonly used needles are 1-inch, 25-gauge or 1.5-inch, 22-gauge Quincke needles.

- The thecal sac may be entered within less than 0.5cm of needle penetration from skin.

- Local anesthetic should be administered after obtaining CSF. The recommended medication and dosage is 0.5% isobaric bupivacaine, 1 mg/kg to a maximum dose of 5 mg (1 mL).4 This dosage, in children up to 12 months of age, is usually adequate for surgeries lasting 60-90 minutes.

- Clonidine 1 mcg/kg may be added to the local anesthetic to extend the duration of the block to approximately 90-120 minutes. This dosage has been shown to be safe without increasing the incidence of side effects (e.g., excessive sedation, bradycardia, or hypotension).5

- After injection of local anesthetic, care must be taken to not lift the patient’s legs above the head to reduce the risk of a high spinal.

- An IV catheter is usually placed in a lower extremity once sensory anesthesia has been obtained. A blood pressure cuff is placed on the lower extremity opposite of the IV.

Intraoperative Care

- After the neuraxial anesthetic reaches peak effect, the patient will usually fall into natural sleep without additional sedation. Supplementary oxygen should be available, but is usually not needed.

- If the child is moving or fussy, block efficacy should be assessed. If the block has failed to set up within approximately 10 minutes, conversion to general anesthesia should be considered.

- If the block is adequate, but the patient is moving enough to disturb the surgical field, a pacifier and 24% sucrose solution (e.g. Sweet-ease or TootSweet) with a calming voice can be enough to soothe the child to sleep. Intravenous dexmedetomidine or other sedation may be administered if nonpharmacologic methods are ineffective.

- The first sign of a high spinal may be apnea. If a high spinal is suspected, temporary assisted ventilation or conversion to general anesthesia with an endotracheal tube may be required, though this is rare.

Postoperative Care

- There is no “wake-up” time needed after spinal anesthesia. Patients may be transported to the postanesthesia care unit phase 1 or 2, if available, or intensive care unit immediately after the completion of surgery and may take food by mouth immediately, if appropriate.

- Preterm neonates and young term neonates are at risk for apnea in the recovery period, and spinal anesthesia decreases the incidence of early, but not late apnea when compared to general anesthesia. As such, discharge criteria for ex-preterm infants who receive spinal anesthesia are the same as for general anesthesia.6

References

- Whitaker EE, Williams RK. Epidural and spinal anesthesia for newborn surgery. Clin Perinatol. 2019;46(4):731-43. PubMed

- Williams RK, Adams DC, Aladjem EV, et al. The safety and efficacy of spinal anesthesia for surgery in infants: the Vermont Infant Spinal Registry. Anesth Analg. 2006;102(1):67-71. PubMed

- McCann ME, Withington DE, Arnup SJ, et al. GAS Consortium. Differences in blood pressure in infants after general anesthesia compared to awake regional anesthesia (GAS study)-A prospective randomized trial). Anesth Analg. 2017;125(3):837-45. PubMed

- Suresh S, Ecoffey C, Bosenberg A, et al. The European society of regional anaesthesia and pain Therapy/American society of regional anesthesia and pain medicine recommendations on local anesthetics and adjuvants dosage in pediatric regional anesthesia. Reg Anesth and Pain Med. 2018;43(2):211-6. PubMed

- Trifa M, Tumin D, Whitaker EE, et al. Spinal anesthesia for surgery longer than 60 min in infants: experience from the first 2 years of a spinal anesthesia program. J Anesth. 2018;32(4):637-40. PubMed

- Davidson AJ, Morton NS, Arnup SJ, et al. Apnea after awake regional and general anesthesia in infants: The general anesthesia compared to spinal anesthesia study--comparing apnea and neurodevelopmental outcomes, a randomized controlled trial. Anesthesiology. 2015;123(1):38-54. PubMed

Other References

- Whittaker E, Sinskey J. Spinal anesthesia in neonates and infants. OA-SPA Ask the Expert Podcast. November 2020. Link

Copyright Information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.