Copy link

Subacute Bacterial Endocarditis Prophylaxis

Last updated: 06/30/2025

Key Points

- Subacute bacterial endocarditis (SBE) is a rare, potentially life-threatening disease caused by infection of the heart valves.

- SBE is most often caused by viridans streptococci, the predominant commensal bacteria of the mouth. Thus, a connection is believed to exist between SBE, oral hygiene, and dental procedures.

- Antimicrobial prophylaxis against SBE is recommended only for a small subset of patients with predisposing conditions, who are undergoing specific procedures likely to cause bacteremia with viridans streptococci.

Introduction

- Infective endocarditis (IE) refers to an infection of the lining of the heart, but it usually affects the heart valves and surrounding structures.1

- There are two forms of IE: acute IE and SBE.

- Acute IE develops suddenly and may become life-threatening within days.

- SBE is a rare type of IE that primarily involves valvular tissues, although the endocardium or implanted devices may also be infected.1

- SBE progresses over a period of weeks to months and places the patient at risk for significant local and systemic complications. In this summary, we will review the pathophysiology, risk factors, and management of SBE.

Microbiology/Pathophysiology

- SBE is most commonly caused by streptococcal species, especially viridans group streptococci (VGS).1 Studies have shown that bacteremia with S. mutans, S. sanguinis, and S. gallolyticus is significantly associated with IE.

- IE can be caused by other species, especially Staphylococcus aureus; however, infection with S. aureus causes an acute form of endocarditis, as opposed to SBE. S. aureus is strongly associated with acute endocarditis of the tricuspid valve in intravenous (IV) drug users.

- Because VGS species are the most common organisms in the mouth, these infections have been associated with poor dental hygiene and invasive dental procedures. However, routine activities such as chewing food and brushing teeth can cause the same levels of bacteremia as seen in dental procedures, and recent evidence has challenged the purported relationship between IE and dental procedures.2

- The HACEK group (Hemophilus spp., Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans, Cardiobacterium hominis, Eikenella corrodens, Kingella spp.) includes a group of fastidious, gram-negative bacilli that are difficult to detect via blood culture. These HACEK species are responsible for less than 5% of all IE cases.1

Clinical Risk Factors for the Development of SBE - SBE normally infects the valves of the heart, most commonly the mitral valve. IE is strongly associated with damage to the endocardium. Therefore, any pre-existing lesion can promote SBE.3 Congenital heart disease, chronic rheumatic heart disease, degenerative valve lesions, artificial valves, and previous SBE are all risk factors for SBE.

Local and Systemic Complications of SBE

- IE may result in multiple local consequences, primarily related to the deposition of infected material or the spread to adjacent tissue.4 Local consequences include:

- Valvular regurgitation due to improper apposition of infected valve leaflets.

- Abscesses in the myocardium with tissue destruction and possible conduction system abnormalities.

- Aortitis due to spread of the infection.

- Patients with prosthetic valves experience additional complications in the setting of IE.5 Consequences of IE in patients with prosthetic valves (in addition to those listed above) include:

- valve ring abscesses;

- obstructing vegetations; and

- mycotic aneurysms, which are manifested by valve obstruction, dehiscence, and conduction disturbances.

- Systemic consequences of endocarditis are most often secondary to embolization of infected material or chronic inflammation.6 These include:

- Infectious emboli which may cause stroke, paralysis, blindness, ischemia of the extremities, splenic or renal infarction, pulmonary embolism, and acute myocardial infarction

- Metastatic abscesses, especially in the spleen, kidneys, brain, and/or soft tissues

- Renal infarction or abscess, or glomerulonephritis

- Vertebral osteomyelitis and septic arthritis

- Roth spots: round, white spots on the retina surrounded by hemorrhage

- Osler nodes: tender raised lesions on the finger or toe pads

- Janeway lesions: small, nontender erythematous lesions on the palm or sole

- Anemia secondary to chronic inflammation

- Nail bed splinter hemorrhage

- In-hospital mortality rate for patients with IE is 18 to 23 percent.3

Prophylactic Measures Against the Development of SBE

- Maintaining oral hygiene is crucial in reducing the risk of gingivitis and periodontitis, as well as the risk of bacteremia. Individuals at risk for IE should make regular visits to a dental professional, brush their teeth regularly, and use dental floss.7

- The American Heart Association (AHA) updated their guidelines for antibiotic prophylaxis in 2007, based on the conclusion that bacteremia resulting from activities of daily living is much more likely to cause IE than bacteremia following a dental procedure, and that routine antibiotic prophylaxis would prevent a very small number of cases, ultimately doing more harm than good. Therefore, the AHA only recommends IE antibiotic prophylaxis for a small subset of patients undergoing certain procedures, listed below.8 Follow-up studies since 2007 have not led to any suggested changes in the guidelines.

- Antimicrobial prophylaxis for the prevention of IE is recommended only for patients with the following cardiac conditions:

- Prosthetic heart valve or prosthetic valve repair material, including:

- Prosthetic valve (surgical or transcatheter)

- Valve repair with prosthetic material (including annuloplasty rings or clips)

- Previous, relapsed, or recurrent IE

- Certain types of congenital heart defects (CHD), including:

- Unrepaired cyanotic CHD (patients with palliative shunts and conduits are still considered unrepaired)

- Completely repaired CHD with prosthetic material or device, during the first dix months after repair

- Repaired CHD with residual defect at the site or adjacent to the site of a prosthetic patch or prosthetic device

- Prosthetic pulmonary artery valve or conduit

- Cardiac transplant recipients who develop cardiac valvulopathy

- Prosthetic heart valve or prosthetic valve repair material, including:

- Antimicrobial prophylaxis for the prevention of IE is recommended in patients with the conditions listed above who are undergoing a procedure that involves1:

- Manipulation of gingival tissues or the periapical region of a tooth, and procedures that penetrate the oral mucosa (e.g., dental extraction, dental implant placement, root canal, periodontal procedures such as scaling, root planning, and probing).

- Incision or biopsy of the respiratory mucosa (e.g., bronchoscopy with biopsy, tonsillectomy, and/or adenoidectomy)

- Established infection of the skin, muscle, genitourinary tract, or gastrointestinal tract

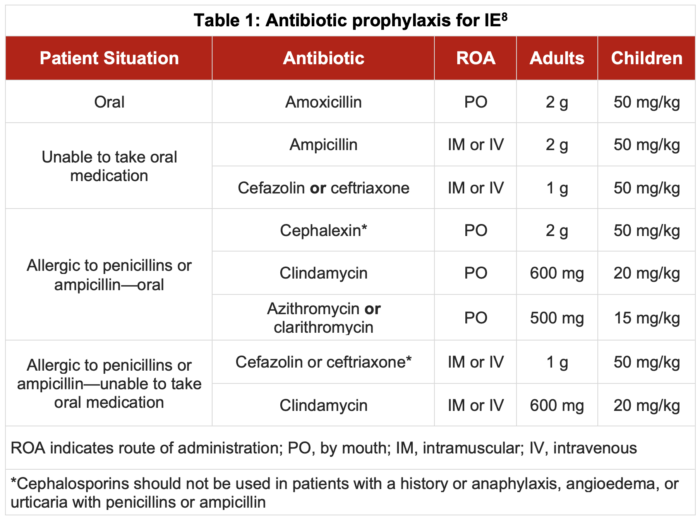

- Antibiotic prophylaxis should be administered 30-60 minutes before the procedure. Table 1 outlines the antibiotic regimens suggested by the AHA:

- For patients with a history of IE and patent ductus arteriosus (PDA) without severe pulmonary hypertension or ventricular septal defect (VSD), closure of the PDA or VSD is warranted to prevent recurrent IE.9

- Antibiotic prophylaxis is not recommended for routine gastrointestinal or urologic procedures.

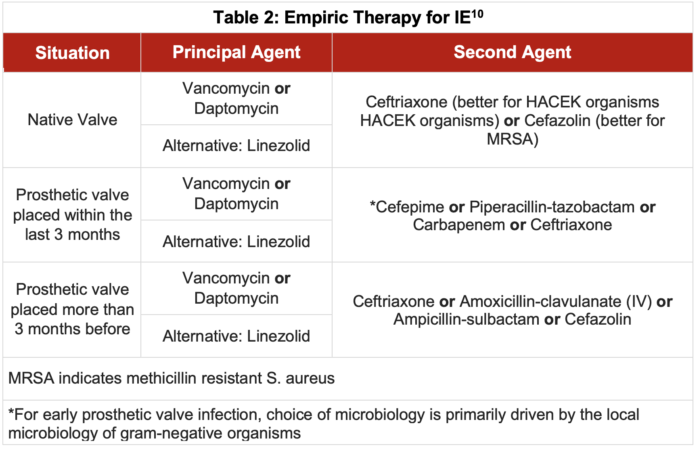

Treatment of Diagnosed SBE - Multiple blood cultures should be taken before initiation of antibiotics. There is scant high-quality evidence comparing the use of different antimicrobials in the empiric treatment of IE.10 Generally, vancomycin or daptomycin is used as a principal agent to empirically treat IE due to their action against S. aureus (including methicillin-resistant S. aureus), streptococcal species, and most enterococci. A β-lactam, such as ceftriaxone or cephazolin, is a reasonable second-line agent, and may be adequate by itself if there is minimal concern for staphylococci or enterococci.

- Table 2 outlines the antibiotic regimens recommended for empiric treatment of IE.

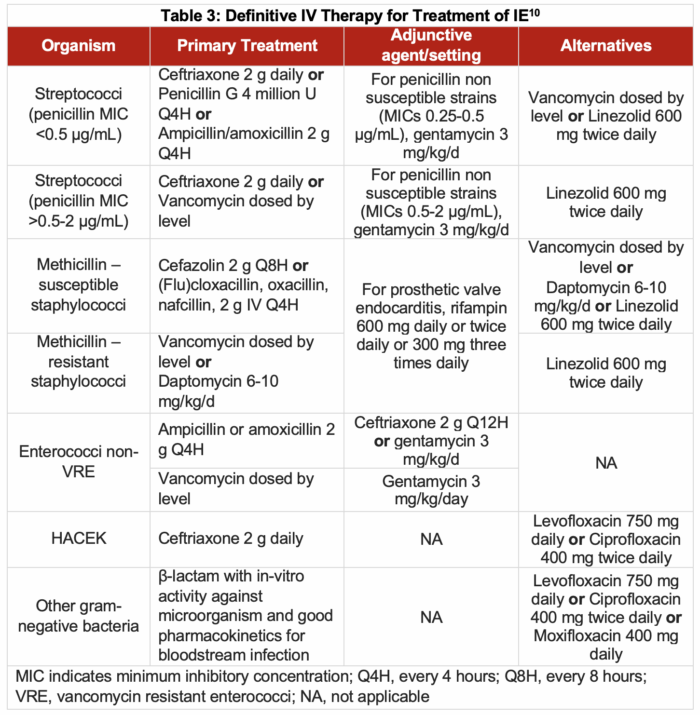

- Unfortunately, little clinical data is available to evaluate the relative effectiveness of different regimens for definitive therapy. Therefore, suggestions are based on historical practice.

- Table 3 outlines the IV antibiotic regimens recommended for definitive treatment of IE.

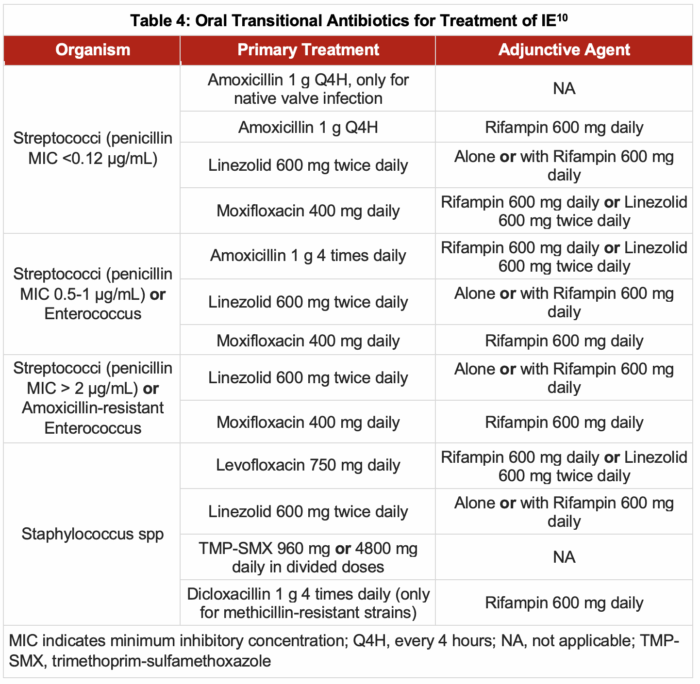

- Transition to oral therapy from initial IV therapy is an option for treating patients with IE who can tolerate it. Patients eligible for switching to oral antibiotics include the following:

- Clinically stable without immediate indication for procedural source control or cardiac surgery

- Have cleared or are clearing their bacteremia without the need for source control

- Have an oral antibiotic regimen available to which their etiologic organism is susceptible

- Are likely to absorb the antibiotic from the gastrointestinal tract

- Have no socioeconomic determinants of health, rendering IV therapy the preferred route

- Table 4 outlines the antibiotic regimens recommended for transitioning to an oral course of antibiotics.

- Valvular surgery also plays an important role in the treatment of IE.11

- For left-sided native valve endocarditis (NVE), early valve surgery is indicated for cases of valve dysfunction complicated by heart failure, intracardiac abscess, difficult-to-treat pathogen, and/or persistent infection.

- For right-sided NVE, valve surgery is indicated for cases of large vegetations of over 20 mm, recurrent septic pulmonary emboli, highly resistant organisms, or persistent bacteremia. Severe tricuspid regurgitation causing right heart failure is a rare complication requiring surgical intervention.

- For patients with a prosthetic valve, early surgery is recommended for complications similar to left and right NVE.

- Emboli in patients with IE can cause a variety of complications. The limited data that exists suggest that neither aspirin nor anticoagulant therapy reduces the risk of embolism in patients with IE. Therefore, neither antiplatelet nor anticoagulant therapy is recommended in patients with IE, except for those with conditions that also pose a risk of thrombosis.

- Patients for whom anticoagulant therapy may be recommended are those with prosthetic valves, atrial fibrillation, or venous thromboembolism. However, the benefit of giving anticoagulants must be balanced by the risk of bleeding.

- Patients for whom antiplatelet therapy may be recommended are those with coronary stents and some patients with coronary artery disease. Patients taking aspirin for secondary prevention of an ischemic stroke or primary prevention of cardiovascular disease and cancer should have their aspirin suspended during treatment of IE due to the major risk of bleeding.

References

- Armstrong GP. Infective endocarditis. Merck Manual. Updated 2024/07. 2024. Link

- Chen PC, Tung YC, Wu PW, et al. Dental procedures and the risk of infective endocarditis. Medicine (Baltimore). 2015;94(43):e1826. PubMed

- Sebastian SA, Co EL, Mehendale M, Sudan S, Manchanda K, Khan S. Challenges and updates in the diagnosis and treatment of infective endocarditis. Curr Probl Cardiol. 2022;47(9):101267. PubMed

- Kelley RE, Kelley BP. Heart-brain relationship in stroke. Biomedicines. 2021;9(12):1835. PubMed

- Cuervo G, Quintana E, Regueiro A, et al. The clinical challenge of prosthetic valve Eendocarditis: JACC focus seminar 3/4. J Am Coll Cardiol. Apr 16 2024;83(15):1418-30. PubMed

- Butler NR, Courtney PA, Swegle J. Endocarditis. Prim Care. Mar 2024;51(1):155-69. PubMed

- Coll PP, Lindsay A, Meng J, et al. The prevention of infections in older adults: Oral health. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2020;68(2):411-6. PubMed

- Wilson WR, Gewitz M, Lockhart PB, et al. Prevention of Viridans group streptococcal infective endocarditis: A scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2021;143(20):e963-e978. PubMed

- Long B, Koyfman A. Infectious endocarditis: An update for emergency clinicians. Am J Emerg Med. 2018;36(9):1686-92. PubMed

- McDonald EG, Aggrey G, Aslan AT, et al. Guidelines for diagnosis and management of infective endocarditis in adults: A wikiguidelines group consensus statement. JAMA Netw Open. 2023;6(7):e2326366. PubMed

- El-Dalati S, Cronin D, Shea M, et al. Clinical practice update on infectious endocarditis. Am J Med. 2020;133(1):44-49. PubMed

Copyright Information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.