Copy link

Regional Anesthesia for Ophthalmic Surgery

Last updated: 09/09/2025

Key Points

- Ophthalmic surgery can be performed under local, regional, or general anesthesia.

- Regional anesthesia is often the standard for most of these procedures, with the selection of the type of block performed often depending on the degree of akinesia required to perform the procedure safely.

- It is critical to understand the management of perioperative complications, including optic nerve perforation, globe perforation, hemorrhage, local anesthetic toxicity, and systemic complications.

Introduction

- Ophthalmic surgeries are among the most frequently performed procedures in the elderly, ranging from simple cataract extractions to complex retinal or orbital surgeries.

- Although these are typically considered low-risk procedures, they are often performed on patients with significant comorbidities such as diabetes, hypertension, coronary artery disease, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.3

- Intraoperative patient movement – whether under general anesthesia or monitored anesthesia care- is the leading cause of complications, often resulting in needle trauma during orbital blocks.3

- Despite the overall low incidence of anesthesia-related complications, careful patient selection, anesthetic planning, and technique are critical to minimizing risk.

Ocular Anatomy

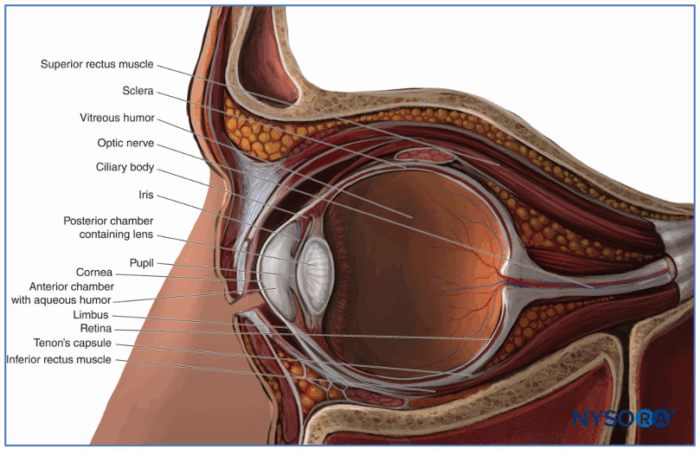

- The eye is a spherical structure measuring approximately 24 mm in diameter, composed of three distinct layers:

- Sclera – the outermost fibrous layer that forms the white of the eye, which is continuous with the transparent cornea at the front.

- Uveal tract – includes the choroid (rich in blood vessels), the ciliary body (responsible for producing aqueous humor), and the iris (which regulates the amount of light entering the eye).

- Retina – the innermost layer containing highly specialized neural tissue, continuous with the optic nerve, and is prone to detachment due to its lack of direct capillary supply.

- The pars plana, a region between the limbus and retina, is commonly used as a safe access point for vitrectomy procedures.3

Figure 1. Illustration of the globe (sagittal section). Used with permission from Local and regional anesthesia for ophthalmic surgery. NYSORA.4

- Vascular Supply:

- The ophthalmic artery, a branch of the internal carotid artery, supplies most of the blood to the eye.

- Venous drainage occurs via the superior and inferior ophthalmic veins, which empty directly into the cavernous sinus.

- Innervation:

- The eye and surrounding structures receive sensory and motor innervation primarily from cranial nerves II through VII.

Preoperative Evaluation

- Evaluate the patient’s ability to lie flat and remain still, which is critical for successful surgery under regional anesthesia.

- History of anticoagulant use, previous eye surgeries, or axial eye length greater than 25 mm should be reviewed.

- Systemic effects of commonly used ophthalmic medications, such as beta blockers or muscarinic agonists, should be noted.

- Standard preoperative fasting guidelines must be followed to reduce aspiration risk.

Intraoperative Considerations

Sedation and Positioning

- Sedation should be minimal and typically involves short-acting agents like midazolam or remifentanil to reduce movement during block placement.

- The head and arms should be secured, and the head should be slightly elevated to minimize venous congestion.

- To avoid fire hazards, low oxygen concentrations should be used near the surgical field, and any increase should be communicated to the surgeon.

- Anesthesia can be done under regional or general anesthesia. Avoid nitrous oxide in patients with recent intraocular gas bubble injections due to the risk of vision-threatening expansion.

- General anesthesia is typically reserved for children or patients unable to cooperate due to cognitive impairment, anxiety, or physical limitations.

Type of Regional Anesthesia

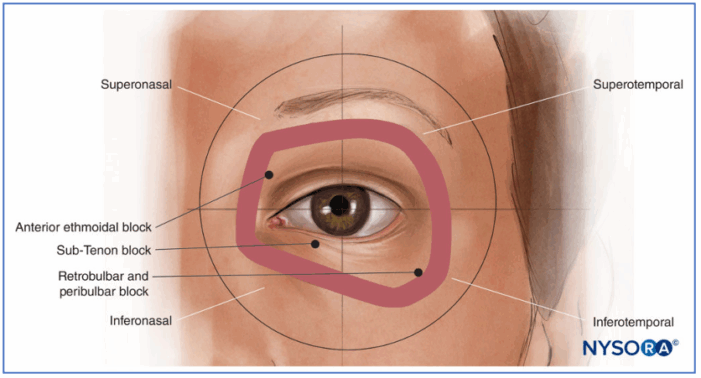

Figure 2. The globe can be divided into quadrants. The figure demonstrates the preferred quadrant of approach for the respective blocks listed above. Used with permission from Local and regional anesthesia for ophthalmic surgery. NYSORA.4

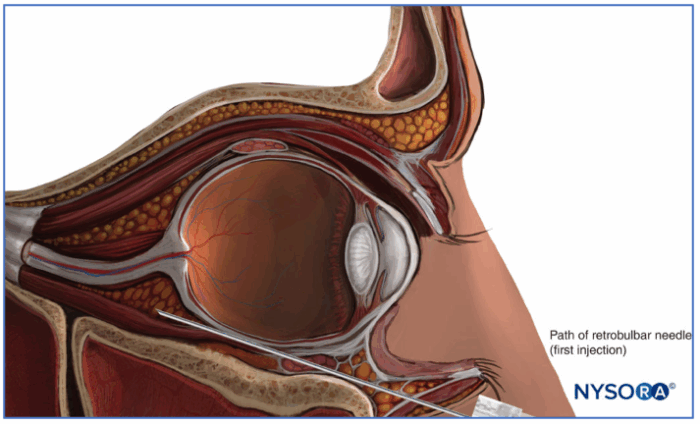

Retrobulbar Block (Intraconal)

- Local anesthetic is injected into the intraconal space formed by the extraocular muscles.

- It provides rapid onset and profound akinesia but carries higher risks such as globe perforation and brainstem anesthesia.

- This technique is relatively contraindicated in patients with elongated axial length due to increased risk of posterior globe injury.

- Insert the needle close to the orbital floor until the globe equator is passed, after which the needle angle is then adjusted upwards and medially to advance into the intraconal space.

Figure 3. Path of retrobulbar needle. Used with permission from Local and regional anesthesia for ophthalmic surgery. NYSORA.4

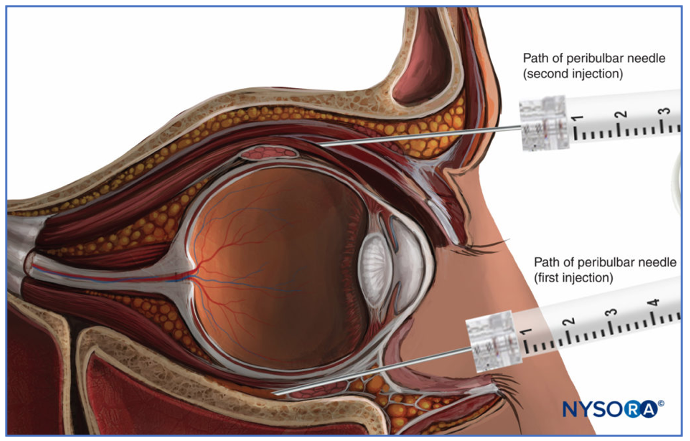

Peribulbar Block (Extraconal)

- The anesthetic is deposited outside the muscle cone, resulting in what is commonly considered to be a safer profile, though some studies show no difference in complications.1

- The classical technique involves two injections.

Figure 4. Path of the first and second injection of the classical technique for the peribulbar nerve block. Used with permission from Local and regional anesthesia for ophthalmic surgery. NYSORA.3

- Onset is slower than the retrobulbar block (around 5 minutes), but it effectively immobilizes the eye, including the eyelids.

- It requires a larger volume of anesthetic (typically 6-12 mL) and is associated with a lower risk of serious complications as compared to the retrobulbar block.

- Please see a video from the University of Iowa Ophthalmology.5 Link

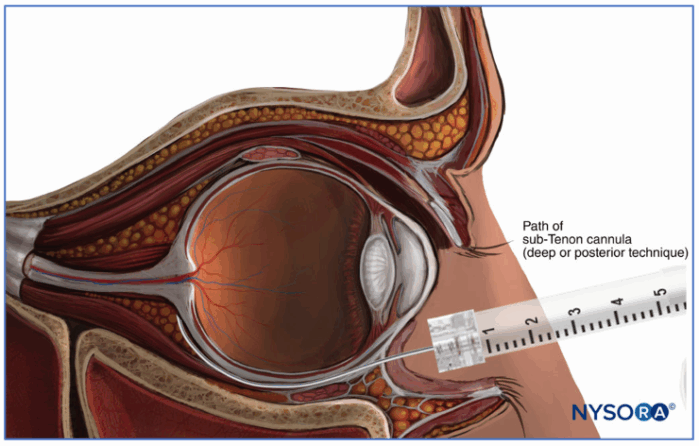

Sub-Tenon Block

- A blunt cannula is used to introduce anesthetic beneath Tenon’s capsule, avoiding sharp needles. Please see a video from the University of Iowa Ophthalmology.5 Link

Figure 5. Needle path for a sub-tenon nerve block. Used with permission from Local and regional anesthesia for ophthalmic surgery. NYSORA.4

- This technique minimizes the risk of globe perforation and is ideal for patients on anticoagulants.

- It is widely used in the UK and provides rapid onset but variable akinesia, depending on the volume injected.

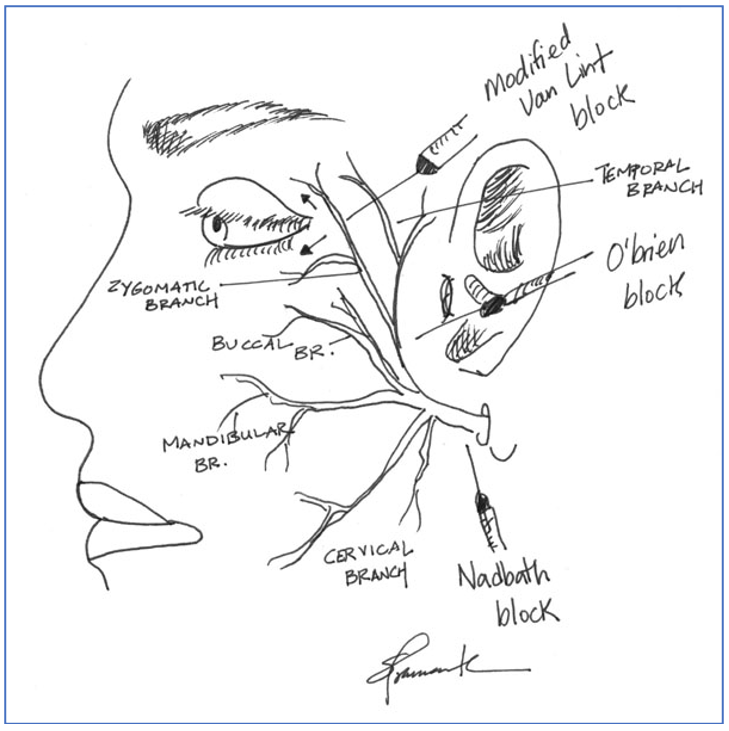

Facial Nerve Block

- This block inhibits involuntary eyelid movement, preventing spikes in intraocular pressure and surgical interference. Often used in conjunction with retrobulbar blocks with eyelid akinesia is insufficiency.

- There are multiple techniques used to block the facial nerve, including the following, listed from more peripheral to most proximal.

- Van Lint Block

- Targets the terminal branches of the facial nerve

- Inject 2-4 mL of local anesthetic 1 cm lateral to the orbital rim.

- A modified approach moves the injection 1 cm further lateral to reduce lid edema.

- O’Brien Block

- Blocks the proximal trunk near the mandibular condyle

- Inject 3 mL after coming into contact with the periosteum.

- Nadbath-Rehman Block

- Inject 3 mL between the mastoid process and mandible to block the full facial nerve trunk.

- It often causes transient facial droop and carries a risk due to its proximity to major vessels and nerves.

Figure 6. Common facial nerve blocks. Used with permission from Pramanik S, Doan A. Retrobulbar block, peribulbar block, and common nerve blocks used by Ophthalmologists. University of Iowa Department of Ophthalmology and Visual Sciences. February 27, 2005.5

Local Anesthetic Solutions

- A mixture of lidocaine 2% and bupivacaine 0.75% is commonly diluted for a balanced onset and duration.2

- Ropivacaine 0.75% is an alternative with less injection pain and a good analgesic profile.2

- Hyaluronidase is often added to facilitate diffusion, reduce orbital pressure, and improve block quality.2

Topical Anesthesia

- Suitable for brief, low-risk procedures like cataract extraction using phacoemulsification.

- Anesthetic gels or drops are applied to the eye surface, preserving vision and avoiding needle-related complications.

- The absence of akinesia requires the patient to remain completely still, making it unsuitable for anxious or uncooperative individuals.

Management of Perioperative Complications

- Complications Mnemonic: OPHTS

- O: Optic nerve perforation

- P: Globe perforation

- H: Hemorrhage

- T: Toxic reactions from local anesthetics

- S: Systemic effects

- Optic Nerve Perforation

- Extremely rare, but it can lead to permanent vision loss.

- Globe Perforation:

- Serious risk, particularly in patients with high myopia.

- It should be suspected with sudden pain, vision loss, or hypotony during block placement.

- Immediate ophthalmologic assessment with ophthalmoscopy or ultrasound is required.

- Surgery is usually postponed, and further injections should be avoided to prevent ocular explosion.

- Retrobulbar Hemorrhage:

- Serious risk, especially with retrobulbar blocks

- Characterized by increased intraocular pressure, resulting in sudden eye protrusion and vision loss.

- This is a medical emergency; a lateral canthotomy may be needed to relieve pressure.

- Depending on severity, the procedure may need to be rescheduled.

- Brainstem Anesthesia:

- Occurs due to anesthetic spreading through the optic nerve sheath into the brainstem.

- Presents with symptoms like apnea and cardiac instability, requiring immediate airway and hemodynamic support.

- Lipid emulsion therapy should be initiated if systemic local anesthetic toxicity is suspected.

- Systemic Local Anesthetic Toxicity:

- Manifests as seizures, arrhythmias, or cardiovascular collapse leading to cardiac arrest.

- Treatment includes lipid emulsion bolus (1.5 mL/kg) followed by continuous infusion and supportive care.

- Avoid calcium channel blockers, beta-blockers, and large epinephrine doses during resuscitation.

- Oculocardiac Reflex Link

- Mechanism:

- The afferent limb of the reflex arc originates from the ophthalmic division of the trigeminal nerve, transmitting signals to the brainstem.

- The efferent limb involves the vagus nerve, which can lead to bradycardia, atrioventricular block, ectopic beats, or even asystole.

- Triggers:

- The reflex is commonly triggered by pressure on the globe or traction on extraocular muscles, particularly the medial rectus.

- It is most frequently observed during pediatric strabismus surgeries due to muscle manipulation.

- Exacerbating Factors:

- Conditions such as hypoxia, hypercapnia, or insufficient anesthetic depth can amplify the oculocardiac reflex response.

- Management:

- The first step is to halt the surgical stimulus causing the reflex.

- Adequate oxygenation and anesthetic depth should be ensured to stabilize the patient’s condition.

- Anticholinergic agents like glycopyrrolate or atropine are administered to counteract persistent bradycardia; epinephrine is rarely required.

- Mechanism:

- Extraocular Muscle Injury:

- It can result from inadvertent intramuscular injection of an anesthetic, leading to postoperative strabismus.

- Risk increases with higher concentrations of lidocaine or repeated injections.

- Venous Air Embolism:

- A rare but potentially fatal event associated with air-fluid exchange during vitrectomy.

- Clinicians should monitor for signs such as sudden hypotension or hypoxia and manage supportively.

References

- Alhassan MB, Kyari F, Ejere HOD. Peribulbar versus retrobulbar anaesthesia for cataract surgery. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;2015(2):CD00408. PubMed

- Anesthesia for elective eye surgery. UpToDate. Accessed August 4, 2025. Link

- Gropper MA, Eriksson L, Fleisher LA, Cohen NH, Leslie K, Johnson Akeju O, eds. Anesthesia for Ophthalmic Surgery. In: Miller’s Anesthesia. 2 Volume Set. 10th ed. Elsevier; 2024: Chapter 69.

- Local and regional anesthesia for ophthalmic surgery. NYSORA. Accessed August 4, 2025. Link

- Pramanik S, Doan A. Retrobulbar Block, Peribulbar Block, and Common Nerve Blocks Used by Ophthalmologists. University of Iowa Department of Ophthalmology and Visual Sciences. February 27, 2005. Accessed August 6, 2025. Link

Other References

- Pramanik S, Doan A, Pramanik S, Oetting T, Weingeist T. Retrobulbar Block, Peribulbar Block, and Common Nerve Blocks Used by Ophthalmologists. University of Iowa. Ophthalmology and Visual Sciences. Created: February 27, 2005. Accessed: September 9, 2025. Link

Copyright Information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.