Copy link

Preparation and Preoperative Considerations for Neurodiverse Patients

Last updated: 04/03/2024

Key Points

- Neurodiverse patients thrive on routine and may find new changes stressful. Therefore, the aim of the perioperative care of neurodiverse patients is to provide a structured and consistent environment to decrease the risk of adverse events.

- Through discussion with parents/caregivers, recognizing and addressing potential stressors is essential to supporting children with autism spectrum disorder during their perioperative visit.

- An individualized coping plan is imperative to ensure their comfort and well-being.

Introduction

Neurodiversity

- Neurodiversity is a nonmedical term that describes people whose brain develops or works differently for some reason. It includes autism spectrum disorder (ASD), attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), dyslexia, intellectual disabilities, sensory processing disorders (SPD), and social anxiety.

Autism Spectrum Disorder

- ASD is a neurodevelopmental disorder that is manifested by qualitative impairment in social interactions, qualitative impairment in verbal and nonverbal communication, and restricted repetitive and stereotypical patterns of behavior, interests, and activities.

- ASD is an umbrella term that includes:1

- Autistic disorder

- Asperger syndrome (no longer used as a diagnostic term, rather diagnosed as autism with low support needs)

- Pervasive developmental disorder – not otherwise specified

- The severity of ASD is based on social communication impairments and restricted, repetitive patterns of behavior.

- The prevalence of ASD has increased over time to 1 in 36 due to better ascertainment and broadening of the diagnostic criteria.

- Children with autism often exhibit distinct behaviors categorized into two primary types:

- Stimming is a self-stimulatory behavior characterized by involuntary repetitive movements like rocking or tapping. Patients with ASD often stim to obtain sensory stimulation from outside and as a coping mechanism for sensory regulation and anxiety.

- Meltdowns are characterized by verbal or physical outbursts.

- Coexisting medical issues include:

- Intellectual disability: 55% of children with ASD have an intellectual disability (IQ less than 70), and 16% have moderate to severe intellectual disability.2

- Mental health diagnoses, including anxiety, ADHD, oppositional defiant disorder, and self-injury and/or aggression are common.1

- Epilepsy:- 30% of children with ASD are diagnosed with seizures.1

- Sleep problems: 40-80% of patients with ASD have insomnia.1

- It is essential to know the specific sedatives and antipsychotics the patient is taking for the above comorbidities.

- Patients with ASD have difficulty in understanding nonverbal cues, have difficulty in changes in routines, and therefore, may have difficulty with medical visits.

- Regardless of the level of intelligence, individuals with ASD are better at processing visual rather than spoken information.3

- They prefer predictability and routine. Therefore, any healthcare encounter increases their anxiety levels.

- Children with ASD have an increased rate of hospital contact.4

- They are 2-3 times more likely to experience an injury that needs medical attention.

- They have an increased risk of adverse events occurring during hospitalizations, which is more likely to occur if there is a failure to consider a child’s routine, special interests, sensory sensitivities, and level of understanding.

Sensory Processing Disorder (SPD)

- SPD occurs when the multisensory input is not adequately processed to provide appropriate responses to the demands of the environment.

- 95% of children with autism also have sensory processing differences, and may experience hypersensitivity or hyposensitivity to a wide range of stimuli.

- This may manifest as input-related challenges, which then results in patients displaying sensory-seeking behaviors (stimming) to compensate for low levels of tactile or proprioceptive input.

Preoperative Preparation

Early Identification

- Early identification allows for adequate patient, family, and staff preparation to ensure a successful perioperative course while minimizing possible adverse events.

- If possible, the nursing team for the preoperative and postoperative care unit should be preassigned to provide consistency throughout the process.

- Ideally, a “day of surgery plan” should be circulated to all team members, including the behavioral pathway team, to ensure that everyone involved is well-prepared and informed.

Preoperative Phone Call & Evaluation

- Patient families/caregivers are the child’s best experts and should be consulted regarding how best to take care of the patient in the perioperative environment by providing family-centered care. Therefore, assessing the severity of the patient’s symptoms and behaviors is important.

- It is important to ask the parent standardized questions about their child’s cognitive level, methods of communication, interests, stressors/triggers for maladaptive behavior, sensory challenges, as well as previous medical encounters and how they do with transitions to develop an individualized coping plan.5

- This information can be obtained during preoperative phone calls by child life specialists, nursing staff, and/or anesthesia personnel as designated by organizational policy.

- As they seek comfort in predictability, hospital visits disrupt their routines, making detailed knowledge of their preferences and aversions from the coping plan invaluable. Individualized coping plans allow accommodations for these unique challenges.

- Children with ASD exhibit a spectrum of sensitivity to stimuli, extending from hypersensitivity, where minor sensations can be overpowering, to hyposensitivity, where additional sensory input is sought for comfort.

- Due to their routines, the timing of surgery is an important consideration.

- Consider giving priority times, such as first case starts or preferential times, based on their usual routine.

- Decrease the wait time prior to the start of surgery and consider allowing them to wait in a more familiar space (for example, in their car in the parking lot).

- Providers should attempt to bundle care. For example, determine if there are other imaging studies, lab work, and/or tests to be accomplished during the same anesthetic.

- Social stories may be provided to families prior to arrival to help facilitate a successful experience by decreasing surprises through visual desensitization. These include simple, reassuring descriptions and photos of different places the patient may visit while at the hospital, whom they might meet, and what might happen.

Day of Surgery Preparation

- Admission to the surgical unit

- A specific entrance and parking area should be designated to minimize sensory overload and ensure a smooth arrival.

- A swift and calm entry directly into the preoperative area should be ensured without waiting in the waiting area. This may require changing typical registration pathways.

- For patients who resist leaving their vehicle, it is important have a plan in place for the administration of intramuscular ketamine. Ideally, a trained team should consist of a nurse, child life specialist, and anesthesiologist. Provisions such as a stretcher or wheelchair for transport from the vehicle to the preoperative area, portable pulse oximeter, oxygen cylinder, mask and back-up airway if needed should be available.

- Preoperative Holding Area

- Environmental Considerations6

- Easy identification and notification for staff should be considered. For example, a placard can be placed on the door or a special symbol can be added to on an electronic operating room (OR) board to indicate the presence of a special needs patient. This helps remind staff of the specific considerations needed for the patient’s care.

- Individual sensitivities should be decreased. For example, the environment should be modified to remove potential noxious stimuli, such as bright lights, loud sounds, etc. Sensory adaptive environments are often used in the dental setting to support positive coping and reduce pain and sensory discomfort, allowing for successful outcomes during dental visits.6

- Foot traffic in and out of the room should be limited to maintain a calm and controlled environment.

- Patient Considerations

- Vitals and Measurements: If the patient declines to have vitals taken during the preoperative assessment, the initial set of vital signs can be obtained in the OR. Similarly, if height and weight measurements are refused, these can be retrieved from a recent medical visit or estimated with input from the parents.1

- Patients should be allowed to remain in street clothes if they refuse to change into a hospital gown. Changing clothes may be distressing due to changes in routine and texture of new clothing, which may trigger anxiety-provoking behaviors.

- Instead of placing the identification band on the arm, it can be secured with the staff or another organizational appropriate mechanism.

- Communication: Regardless of level of intelligence, individuals with ASD are better at processing visual rather than spoken information. Visual cues or social stories should be used, if possible. Patients with ASD may require a longer time to make decisions, respond to questions, or accept suggestions. It might appear as if those with autism are answering or did not understand, and so the temptation is to repeat or rephrase the question, both of which can restart the processing time.3

- Patient comfort items should be allowed to be brought into the OR.

- Physical restraint, anger, raising voices, and being emotional can be counterproductive in patients with ASD. If restraint is necessary, it should be used as a last resort. Depending on organizational policies, consent should be obtained by guardians, and public safety should be notified and possibly involved depending prior to restraining a patient.1

- Guardian Considerations

- The anesthetic plan should be discussed with the parent or guardian outside the preoperative room to address any concerns or questions.

- Often, a discussion with guardians if the patient would benefit from a premedication vs. parent-present induction (if allowable at the facility) is very useful.

- Child Life Specialists

- Child life specialists are certified professionals who provide psychosocial support to help children and families cope in the hospital setting.

- Through developmentally appropriate preparation and medical play, child life specialists use play to support positive coping during procedures and other medical experiences in the hospital setting.

- Mask prep: Patients with ASD are better at processing visual rather than spoken, information. A thorough mask preparation session utilizing visuals, such as social stories, may be beneficial.3 Additionally, the use of technology using table-based apps may be considered. An example is the EZ induction app from Little Seed. Link

- Environmental Considerations6

Premedication

- Children experience higher preoperative anxiety if they have a diagnosis of ASD.7

- The parents of ASD children are more likely to say their child would need a premedication as compared to parents of typically developing youth.

- By utilizing a patient’s coping plan, premedication may be avoided in a significant number of patients (up to 60%).

- Patients with ASD are less likely to receive a standard premedication; they are significantly more likely to receive a nonstandard premedication – most commonly intramuscular ketamine.8

- Sometimes, a combination of medications may be necessary in rapidly escalating maladaptive behaviors for the safety of the patient and staff.

- Premedication at home:

- Some patients may need to take premedication at home before leaving. The patient’s medication list should be reviewed for sedatives like clonidine or melatonin. Consider suggesting doubling the morning dose or taking it both morning and night if usually taken only at night.

- Others without sedatives or with severe anxiety may require additional premedication, such as Ativan 1-2 mg or valium 5-10 mg. For patients who have never taken these, if possible, it is a good idea to have them trial it at home a day prior to the hospital visit to avoid paradoxical reactions.

- Premedication in the hospital:

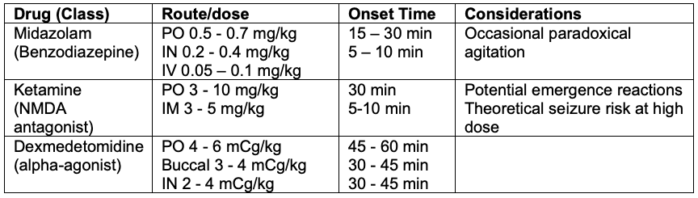

- It is important to discuss the route of premedications with the patient’s guardian or caretaker (Table 1). Depending on the patient’s sensory sensitives they may not tolerate per oral or per nasal routes.

- Per oral (PO) route: One can administer ketamine (2-3 mg/kg) and midazolam (0.3 – 0.5 mg/kg) orally, mixed into their preferred drink to mask bitterness. Alternatively, emptying their favorite juice box and pouring the mixture inside can also disguise it effectively.1

- Intramuscular (IM) route: IM ketamine is a last resort for patients who refuse to drink the premedication, refuse to exit from the car in the parking lot or exhibit rapid escalation in preoperative areas. The patient’s family should be consulted to determine the optimal site for IM ketamine (100mg/ml) administration: deltoid or thigh. Patients with ASD may have varying responses to painful stimuli from sharp needles. Use a long enough needle to ensure intramuscular delivery while prioritizing safety. Administration may be necessary in the parking lot, over clothing if required. Wearing dangling lanyards should be avoided to prevent choking hazards. The patient should be approached slowly to avoid startling them. A distraction technique, such as applying an alcohol wipe on one extremity before quickly injecting on the other side, should be considered.

Table 1. Commonly used preoperative medications for patients with ASD

Induction Techniques

- Speak with “one voice”

- Throughout the induction process, a single individual should be designated to speak, whether it’s the parent, nurse, or anesthesiologist, as the sole communicator. All other participants must be quiet until the child falls asleep.

- Additional help should be available right outside the OR.

- Mask vs. IV Induction: After discussion with family/caregiver, a plan can be developed of the best way to induce general anesthesia. Some patients may benefit from a parental presence during induction, due to the comfort from their parent/caregiver in an unfamiliar environment. Preoperatively, it’s possible to have a conversation with older children who may prefer a preoperatively placed IV after proper education. Distraction technologies and child life specialists may aid in this process.

- Environmental Considerations3

- Allow patient comfort items to be brought with them to the OR

- Decrease light sensitivities by dimming the OR lights

- Utilize a weighted blanket for calm pressure

- To minimize transfers, inducing anesthesia either in the wheelchair or on the transport bed should be considered. Placing a cloth sheet under the patient before induction facilitates smooth transfer to the operating room bed, especially for older, obese children.

- Consider using technology for patients who are cooperative enough to undergo mask induction. PediPop Anesthesia is an example of a free, web-based app that facilitates mask induction in anxious children. Link

References

- Taghizadeh N, Davidson A, Williams K. et al. Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) and its perioperative management. Paediatr Anaesth. 2015; 25: 1076-84. PubMed

- Charman T, Pickles A, Simonoff E, et al. IQ in children with autism spectrum disorders: data from the Special Needs and Autism Project (SNAP). Psychol Med. 2011;41(3):619-27. PubMed

- Doherty M, McCowan S, Shaw SCK. Autistic SPACE: a novel framework for meeting the needs of autistic people in healthcare settings. Br J Hosp Med. 2023;84(4):1-9. PubMed

- Lee L, Harrington RA, Chang JJ, et al. Increased risk of injury in children with developmental disabilities. Res Develop Disabil. 2008; 29(3):247-255. PubMed

- Swartz JS, Amos KE, Brindas M, et al. Benefits of an individualized perioperative plan for children with autism spectrum disorder. Pediatr Anesth. 2017; 27: 856– 62. PubMed

- Cermak SA, Duker LIS, Williams ME, et al. Sensory adapted dental environments to enhance oral care for children with autism spectrum disorders: A randomized controlled pilot study. J Autism Dev Disord. 2015; 45(9): 2876–88. PubMed

- Elliott AB, Holley AL, Ross AC, et al. A prospective study comparing perioperative anxiety and posthospital behavior in children with autism spectrum disorder vs typically developing children undergoing outpatient surgery. Pediatr Anesth. 2018; 28: 142–8. PubMed

- Arnold B, Elliott A, Laohamroonvorapongse D, et al. Autistic children and anesthesia: is their perioperative experience different? Paediatr Anaesth. 2015;25:1103-10. PubMed

- Hazen EP, Ravichandran C, Rao HA, et al. Agitation in patients with autism spectrum disorder admitted to inpatient pediatric medical units. Pediatrics. 2020;145(suppl 1): S108–S116. PubMed

- Vlassakova BG, Emmanouil DE. Perioperative considerations in children with autism spectrum disorder. Curr Opin Anaesthesiol. 2016;29(3):359-66. PubMed

Other References

Copyright Information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.