Copy link

Postpartum Tubal Ligation

Last updated: 06/03/2025

Key Points

- Postpartum ligation (PPTL) is considered a safe and effective form of permanent contraception.

- The procedure exhibits a low complication rate, indicating its suitability for patients during their postpartum hospitalization.

- The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists categorizes PPTL as an urgent procedure, ideally performed within 24 hours following delivery.

- A significant number of patients (~70%) who request PPTL do not receive the procedure, resulting in increased instances of unintended pregnancies.

Introduction

- PPTL is a safe procedure, with mortality rates for laparoscopic procedures estimated near 1-2 per 100,000 procedures (most attributed to hypoventilation and cardiopulmonary arrest during general anesthesia), and intraoperative and postoperative complication rate ranging from 0.1-3.5% related to issues such as intra-abdominal injury, hemorrhage, fever, and thromboembolic events. Anesthesia options include epidural, spinal, or general anesthesia, with the technique selected based on the patient’s needs.1

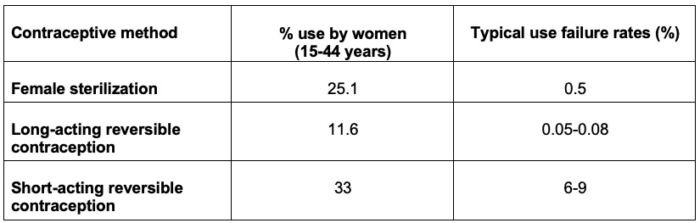

- PPTL or salpingectomy, utilized by 20% of women, is one of the most effective forms of contraception over two years, with a failure rate around 6 per 1,000 procedures over 5 years. In comparison, long-acting reversible contraception, such as intrauterine devices (IUDs), has similar failure rates (0.8% for the copper T380A, 0.2% for levonorgestrel-releasing IUD, and 0.05% for etonogestrel implant).1,2

- Around 39-57% of women who request postpartum sterilization eventually complete the procedure, with a persistently low follow-through rate when completed up to 90 days postpartum (46% of Medicaid patients and 65% of privately insured patients). Almost 50% of women with an unfulfilled request for postpartum sterilization become pregnant within 1 year, twice the rate of those who did not request the procedure.2

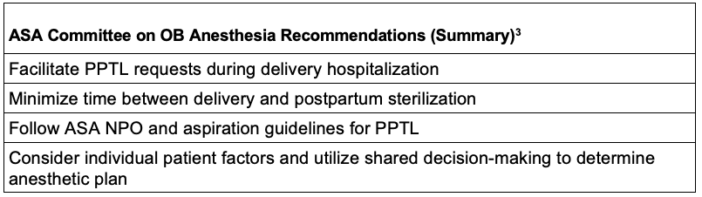

Table 1. Summary of recommendations for postpartum ligation from the ASA Committee on Obstetric Anesthesia; Abbreviation: PPTL, postpartum ligation

Anesthetic Approaches

- General recommendations

- Patients undergoing PPTL must be adequately fasted and should receive aspiration prophylaxis with an H2 blocker and a nonparticulate antacid.

- Contraindications include acutely ill patients, such as those on magnesium for severe pre-eclampsia, peripartum cardiomyopathy, ongoing postpartum hemorrhage, sepsis, coagulopathy, and/or critical care admission.

- Choice of technique: This procedure can be performed under either neuraxial or general anesthesia. Practice guidelines state that there is insufficient evidence to evaluate the benefits of general anesthesia versus neuraxial anesthesia for PPTL; instead, they recommend individualizing the choice of technique to the patient and circumstances.3

- Neuraxial anesthesia

- Risks include itching, nausea, hypotension, postdural puncture headache, and potential neurologic injury.

- Success rates for epidural reactivation may decline over time since delivery, correlated with the time since the epidural catheter was most recently used.4

- A pinprick block extending to T4 is indicated to provide surgical anesthesia.

- Sensitivity to local anesthetics can be reduced by as much as 30% within 8-24 hours postpartum.

- An in-situ, functional epidural can be utilized for anesthesia if present. Caution is recommended as reactivation of an in-situ epidural is most successful within the first 4 hours after delivery, with evidence that reactivation decreases significantly over the first 24 hours.4

- General anesthesia

- Risks include nausea, vomiting, sore throat, difficulty swallowing, hoarse voice, aspiration, injury during airway management, difficult intubation, and uterine atony.

- In the immediate postpartum period, providers should be aware that airway changes can persist or worsen, especially after pushing efforts during the second stage of labor.4 Basic and advanced airway equipment should be readily available, including various endotracheal tube sizes, supraglottic airways, video laryngoscopes, and surgical airway access equipment.3

- Volatile anesthetics are known to contribute to uterine atony during cesarean delivery, and their use in PPTL carries a theoretical risk of decreasing uterine tone.

Timing of Procedure

- PPTL is safe, with a cumulative perioperative complication rate of less than 0.5% total for intra-abdominal injury, hemorrhage, fever, and thromboembolic events.1

- PPTL is preferred to be performed within 24 hours of delivery, as the uterine fundus can be found near the umbilicus at this time and allows for easy access to the salpinges through an infraumbilical mini-laparotomy incision.

- In the immediate postpartum period, the uterine fundus remains near the umbilicus, and the salpinges can be accessed through a single small incision.

- Table tilt and/or Trendelenburg positioning may assist with complex visualization.

- The rate of regret for sterilization is low, around 6 percent for patients who were at least 30 years old at the time of the procedure and around 20 percent for those who were younger than 30. Risk factors for regret include being under 30 years old at the time of the procedure, a longer time interval between delivery and the procedure, and inadequate counseling or information before the procedure.1

Implications for Public Health

- Unintended childbirth results in increased healthcare costs, preventable maternal and fetal morbidity, and mortality.4

- Women with unmet postpartum sterilization express feelings of anger, frustration, anxiety, and dissatisfaction. Up to 57% of women resume sexual activity 6 weeks after delivery, and with the unmet PPTL, this can lead to many unintended pregnancies.4

- Not receiving a PPTL disproportionately affects minorities and the underinsured.4

- Post-Dobbs: While there had been a steady utilization of permanent sterilization in most states before this, permanent sterilization rates for women (18-49 years old) appear to have steadily increased, particularly in banned or near-banned states.6

Table 2. Rates of female contraceptive method use and failure rates7

References

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists' Committee on Practice Bulletins—Gynecology. ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 208: Benefits and risks of sterilization. Obstet Gynecol. 2019;133(3):e194-e207. PubMed

- Access to postpartum sterilization: ACOG Committee Opinion, Number 827. Obstet Gynecol. 2021;137(6):e169-e176. PubMed

- Practice guidelines for obstetric anesthesia. Anesthesiology. 2016; 124 (2): 270-300. PubMed

- Committee on Obstetric Anesthesia. Statement on anesthesia support of postpartum sterilization. American Society of Anesthesiologists. Published October 23, 2024. Accessed May 16, 2025. Link

- Mushambi MC, Kinsella SM, Popat M, Swales H, Ramaswamy KK, Winton AL, Quinn AC; Obstetric Anaesthetists' Association; Difficult Airway Society. Obstetric Anaesthetists' Association and Difficult Airway Society guidelines for the management of difficult and failed tracheal intubation in obstetrics. Anaesthesia. 2015;70(11):1286-306. PubMed

- Xu X, Chen L, Desai VB, et al. Tubal sterilization rates by state abortion laws after the Dobbs decision. JAMA. 2024;332(14): 1204-6. PubMed

- Stuart GS, Ramesh SS. Interval female sterilization. Obstet Gynecol. 2018;131(1):117-24. PubMed

Other References

Copyright Information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.