Copy link

Postpartum Hemorrhage: Etiologies, Risk Factors, and Prevention

Last updated: 07/02/2025

Key Points

- Postpartum hemorrhage (PPH) continues to be the leading cause of maternal mortality globally.

- Predicting and detecting hemorrhage is challenging, as most women who experience PPH do not have risk factors, and vital signs may only change after substantial blood loss.

- Interventions to prevent morbidity secondary to PPH include administering oxytocin, controlled cord traction, and uterine massage.

Introduction

- Obstetric hemorrhage is a leading cause of maternal morbidity and mortality worldwide, particularly in developing nations, with an estimated 14 million women experiencing PPH resulting in 70,000 maternal deaths globally.1

- Although the rate of maternal mortality due to PPH has been decreasing over the last twenty years, it remains one of the leading causes of pregnancy-related mortality in the United States.2

- PPH contributes to 6.9-18.8% of intensive care unit admissions in the United States.

- Most adverse outcomes in hemorrhage are likely preventable, due to factors such as failure to recognize risk factors, inaccurate estimation of blood loss, and delays in resuscitation.

Clinical Presentation

- PPH is defined as 1000 mL of blood loss accompanied by signs or symptoms of hypovolemia within 24 hours after birth, regardless of the route of delivery.

- Primary PPH occurs within 24 hours after delivery, whereas secondary PPH occurs within 24 hours to 12 weeks postpartum.

- Deterioration of vital signs (tachycardia, hypotension) often does not manifest until over 25% of blood volume is lost.

- A careful physical exam is needed to identify the source of bleeding (uterine, cervical, vaginal, periurethral, periclitoral, perineal, perianal, or rectal).

Etiologies and Risk Factors1

- Tone (uterine atony)

- Accounts for 70-80% of PPH

- Typically, uterine contractions (mediated by endogenous oxytocin) lead to the constriction of spiral arteries, which contributes to hemostasis during delivery.

- Risk factors include prolonged labor, multiple gestation, multiple fibroids, high parity, chorioamnionitis, augmented labor, cesarean section, precipitous labor, tocolytic agents, and use of volatile anesthetics.

- Trauma (lacerations, uterine rupture)

- Risk factors for genital tract lacerations include precipitous or operative vaginal deliveries.

- A major risk factor for uterine rupture is a prior uterine incision, classical > low transverse.

- Tissue (retained or abnormally adherent placenta or products of conception)

- Retained placenta is defined as the failure of placental separation within 30 minutes of delivery.

- Placenta accreta occurs in three subtypes:

- placenta accreta, defined as adherence of the placenta to the myometrium without a decidual layer;

- placenta increta, defined as invasion into the myometrium, and;

- placenta percreta, defined as invasion through the uterine serosa.

- Risk factors for placenta accreta include a previous uterine incision or instrumentation, advanced maternal age, multiparity, assisted reproductive techniques, and a low-lying placenta or placenta previa.

- The incidence of accreta rises significantly when placenta previa is present in a patient with one or more previous uterine incisions, with an incidence of greater than 60% in women with placenta previa and three or more prior cesarean deliveries.

- Thrombin (coagulopathy, including disseminated intravascular coagulation)

- Risk factors include massive blood loss, preeclampsia, inherited coagulopathies, therapeutic anticoagulation, severe sepsis, placental abruption, and amniotic fluid embolism.

Medical Management

- Active management of the third stage of labor3

- Bimanual uterine massage

- Prophylactic administration of oxytocin (10U intravenous [IV] or intramuscular)

- Umbilical cord traction

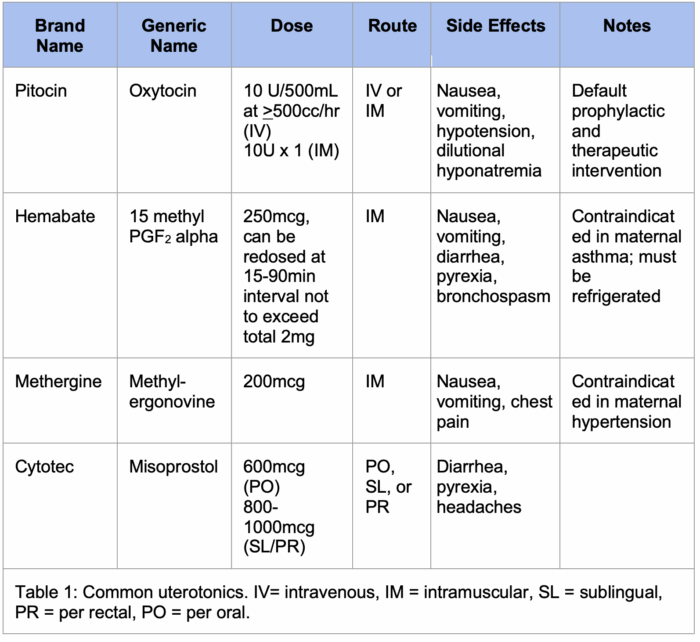

- Administration of additional uterotonics (Table 1)

- Note that no specific supplemental uterotonic has been shown to be superior, and there is considerable variability in use, including the use of multiple agents in rapid succession.

- Please see the OA summary on tocolytics and uterotonics for more details. Link

- Tranexamic acid (TXA)

- The WOMAN randomized controlled trial demonstrated that TXA reduces the risk of death due to bleeding in the setting of PPH without increasing the risk of thrombotic events (1g IV plus additional 1g IV if bleeding continues after 30 minutes.4

- Resuscitation

- Large-bore (> 18-gauge) IV access

- Baseline type and screen, complete blood cell count, coagulation studies, fibrinogen levels; frequent reassessments

- Careful estimation of cumulative blood loss

- Consider the use of rotational thromboelastometry (ROTEM) and thromboelastography (TEG) targeting higher fibrinogen levels in this population.

- Product repletion

- Traditional trauma-based resuscitation (1:1:1 product transfusion) is often employed in the peripartum population. However, this is not supported by hard evidence and may lead to overtransfusion with plasma, which carries additional risks.

- The ratio of products is likely less important than institutional comprehensive maternal hemorrhage plans, including massive transfusion protocols.

- Please see the OA summary Postpartum Hemorrhage: Management for more details. Link

Surgical Management5

- Manual removal of retained tissue +/- ultrasound guidance (if present)

- Laceration repairs (if present)

- Intrauterine tamponade devices

- Bakri balloon

- Ebb system

- Foley catheter(s)

- Packing

- Uterine artery embolization

- Usually employed after medical management and intrauterine tamponade has failed

- Median success rate of 89% (58-98%)

- Vascular ligation sutures

- Median success rate of 92% as a second-line approach to PPH

- Uterine compression (B-Lynch) sutures

- Median success rate of 60-75% as a second-line approach to PPH

- Peripartum hysterectomy

- Carries a substantial risk of bleeding and damage to surrounding structures

Prevention

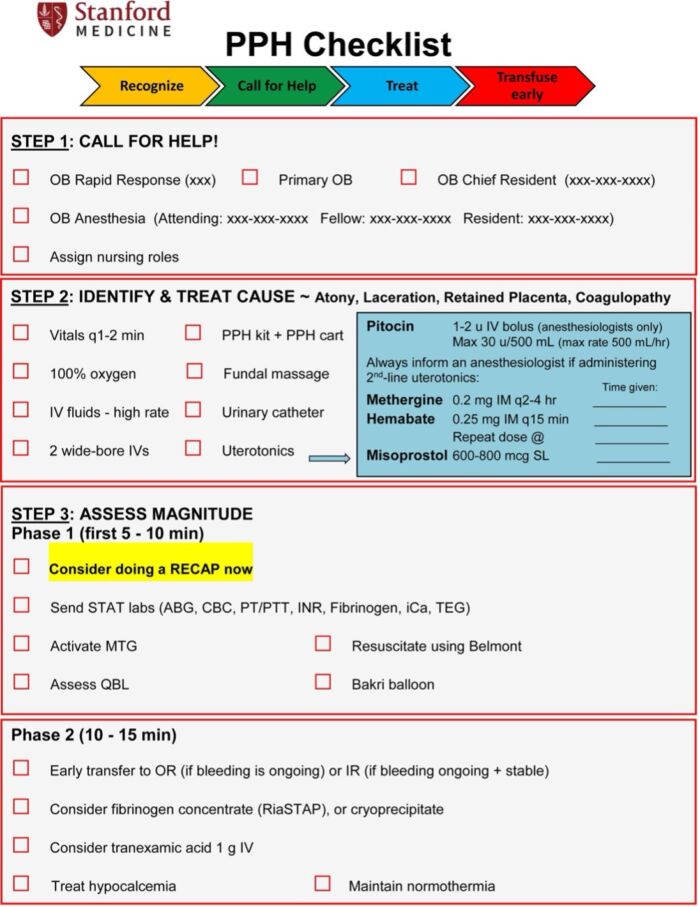

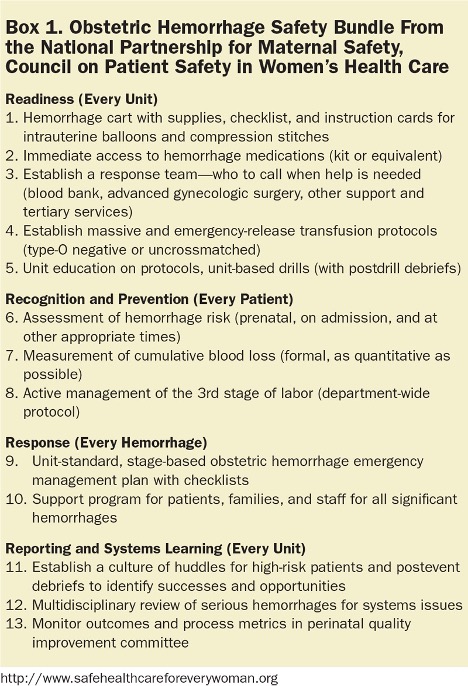

- Morbidity and mortality related to PPH may be reduced with the implementation of hemorrhage bundles, which have been shown to reduce progression of hemorrhage and transfusion needs.7

Figure 1. Example of a postpartum hemorrhage checklist from Lucile Packard Children’s Hospital, Stanford Univeristy.6 CCBY NC ND 3.0.

Figure 2. National Partnership for Maternal Safety: Consensus Bundle on Obstetric Hemorrhage. Used with permission from Anesth & Analg. 2015.7

References

- Practice Bulletin No. 183: Postpartum hemorrhage. Obstet Gynecol. 2017; 130(4):e168-e186. PubMed

- Creanga AA, Syverson C, Seed K, et. al. Pregnancy-related mortality in the United States, 2011-2013. Obstet Gynecol. 2017; 130: 366-373. PubMed

- Begley CM, Gyte GML, Devane D, et al. Active versus expectant management for women in the third stage of labour. Cochrane Database Systematic Rev. 2019;2(2): CD007412. PubMed

- WOMAN Trial Collaborators. Effect of early tranexamic acid administration on mortality, hysterectomy, and other morbidities in women with post-partum haemorrhage (WOMAN): an international, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2017;389(10084): 2105-2116. PubMed

- Sathe NA, Likis FE, Young JL, et al. Procedures and uterine-sparing surgeries for managing postpartum hemorrhage: A systematic review. Obstet Gynecol Survey. 2016; 71(2): 99-113. PubMed

- Abir G, Riley ET, Oakeson AM, et al. Automated alert system of second-line uterotonic drug administration. A & A Practice. 2023; 17(5):e01687. PubMed

- Main EK, Goffman D, Scavone BM, et al. National partnership for maternal safety: Consensus bundle on obstetric hemorrhage. Anesth Analg. 2015:121(1); 142-8. PubMed

Other References

- CMQCC (California Maternal Quality Care Collaborative) OB Hemorrhage Toolkit, v3.0. Link

- ACOG (American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists) Safe Motherhood Initiative for Obstetric Hemorrhage. Link

- OA-SOAP Fellows Webinar Series. Massive Transfusion in Obstetric Hemorrhage. 2023. Link

- OA-SOAP Fellows Webinar Series. Hemorrhage, Coagulopathy, and Transfusion Medicine. 2021 Link

- OA-SOAP Fellows Webinar Series. Risk Stratification for Postpartum Hemorrhage. 2020 Link

Copyright Information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.