Copy link

Postoperative Delirium in Aging Patients

Last updated: 01/27/2023

Key Points

- Postoperative delirium (POD) is characterized by a fluctuating disturbance in consciousness, usually within the first 24-72 h as defined by the DSM-V criteria and is distinct from delayed neurocognitive decline (NCD), formerly known as postoperative cognitive dysfunction.1

- The risk of POD may be reduced by preoperative evaluation via a multidisciplinary team, nonpharmacologic interventions, minimization of known precipitating medications, optimization of pre and postoperative pain control and ICU sedation protocols with dexmedetomidine.2

- To date, insufficient evidence exists to recommend specific anesthetic agents or doses, regional/neuraxial blockade as the primary anesthetic, or the use of prophylactic medications to reduce the risk of POD.2

Introduction

- Patients older than the age of 65 are the fastest growing group of the population, resulting in a significant growth of operative and nonoperative anesthetics administered.1 Postoperative cognitive impairment is common, preferentially seen in the elderly, and it represents a significant increase in morbidity, mortality, and discharge to places other than home. Billions of health care dollars are spent annually secondary to postoperative cognitive impairment.

- Depending on the surgical intervention (i.e., ambulatory, acute hip fracture, cardiac), the reported incidence of POD varies widely from 4% – 65%.1 The nomenclature for perioperative neurocognitive changes can be confusing, but general recommendations are that “perioperative neurocognitive disorders” (NCD) be used as an overarching term for cognitive impairment or change in the perioperative period with subclassifications based on the timing of cognitive changes.3

Definitions

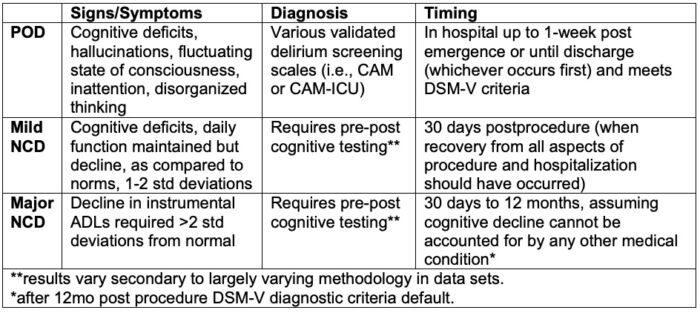

Table 1. Definitions of perioperative neurocognitive changes. Postoperative delirium (POD), mild neurocognitive decline (NCD), major neurocognitive decline (NCD), Confusion Assessment Method (CAM). Adapted from Evered L, et al. Recommendations for the nomenclature of cognitive change associated with anaesthesia and surgery. Br J Anaesth. 2018.121(5):1005–12.3

Pathophysiology

Multiple theories exist regarding the pathophysiology of POD. These theories largely exist from animal models and can only be extrapolated as such. Currently, evidence from human studies is limited.

- Neuroinflammation: Systemic inflammatory mediators, such as C-reactive protein (CRP) and interleukin-6 (IL6), are increased after surgery and remain high during the postoperative period and are associated with an increased risk of POD. Peripheral inflammation can lead to a structural and functional break down in blood-brain barrier integrity, resulting in translocation of inflammatory mediators into the cerebrospinal fluid. Inflammatory mediator accumulation within the CNS results in loss of synaptic plasticity, neuroapoptosis, and impaired neurogenesis.4

- Neurotransmitters: Alterations in acetylcholine (thought to be involved in neuroplasticity, attention, and memory), specifically low levels of acetylcholinesterase, have been shown to be an independent risk factor for POD. POD patients have been found to have lower acetylcholinesterase both preoperatively and up to 2 days postoperatively.4

- Subclinical vascular events: Cerebral ischemia is associated with more than double the risk of POD. Although the risk of postoperative stroke is rare, diseases that increase the risk of cerebral vascular events (hypertension, atrial fibrillation, and previous stroke) are risk factors for POD. Both a reduction in cerebral perfusion pressure and a cerebral perfusion pressure above the autoregulatory limit are also independent risk factors of POD.4

Risk Factors

There are multiple known causes of POD, and it can exist or manifest at any point during the perioperative setting. Certain causes include persistent drug effects, unmasked pre-existing issues (i.e., drugs, alcohol withdrawal, pre-existing cognitive impairment), and physiologic perturbations (i.e., electrolyte imbalance, hypoxia, infection)2 (Tables 2 and 3).

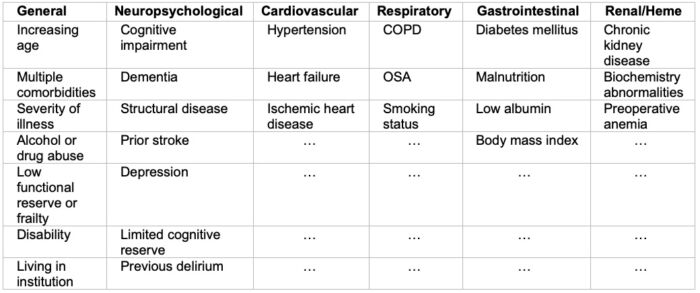

Table 2. System-wise predisposing risk factors for POD. Abbreviations: COPD: chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, OSA: obstructive sleep apnea Adapted from: Hughes CG, et al. American Society for Enhanced Recovery and Perioperative Quality Initiative Joint Consensus Statement on Postoperative Delirium Prevention. Anesth Analg. 2020 June; 130(6); 1572-1590.1

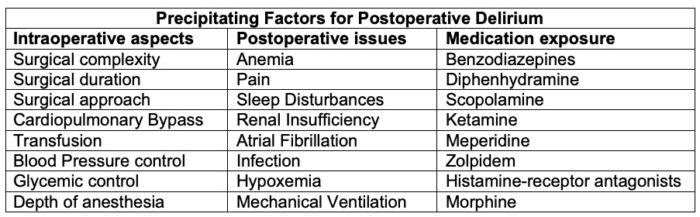

Table 3. Precipitating factors for postoperative delirium. Adapted from: Hughes CG, et al. American Society for Enhanced Recovery and Perioperative Quality Initiative Joint Consensus Statement on Postoperative Delirium Prevention. Anesth Analg. 2020 June; 130(6); 1572-90.1

Anesthetic Considerations4

Preoperative

- Screen for high-risk patients and have informed discussion

- Avoid perioperative polypharmacy

- Avoid prolonged (>6hr) fluid fasting

- Consider comprehensive geriatric assessment via a multidisciplinary approach for high-risk patients

- Develop preoperative pain management plan

- Consider minimally invasive surgical approach, if appropriate; these interventions may reduce risk of POD, but data is conflicting.

Intraoperative Interventions

- Monitor depth of anesthesia

- Varying evidence exists around this intervention and further research is needed.

- Use multimodal opioid sparing analgesia

- Use NSAIDS and acetaminophen, when applicable

- Use dexmedetomidine

- Limit use of potentially inappropriate medications on a risk/benefit basis (AGS Beer’s Criteria®)

- Tricyclic antidepressants

- Histamine-receptor antagonists

- Benzodiazepines

- Gabapentinoids

- Scopolamine

- Avoid hypothermia

- Maintain appropriate hemodynamics

- Maintain euvolemia and consider goal-directed fluid management

Postoperative Interventions

- Prevent nonpharmacologic delirium

- Reorientation to surroundings (limiting staff changes, immediate access to glasses/hearing aids, access to natural light, time keeping devices, reminders about previous events, future planning)

- Cognitive exercises

- Sleep optimization

- Mobilization

- Hydration and nutrition

- Melatonin receptor agonists

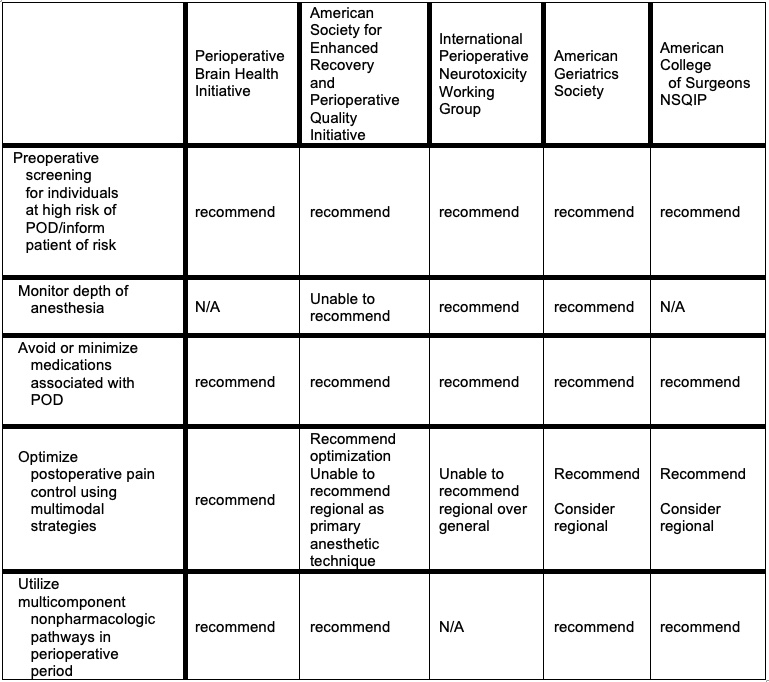

Best practice recommendations from various professional societies for the prevention and management of postoperative delirium are listed in Table 4.5

Table 4. Best practice recommendations from professional societies for the prevention and management of POD. Adapted from: McSwain JR, et al. Perioperative Considerations for Patients with a Known Diagnosis of Dementia. Adv Anesth. 2021; 39:113-132.5

References

- Humeidan, M., Deiner, S. G., & Koenig, N. Postoperative Cognitive Impairment in Elderly Patients. In: Reves JG, Barnett, SR, McSwain JR, & Rooke GA, eds. Geriatric Anesthesiology 3rd Ed. Springer; 2017: 467-480.

- Hughes CG, Boncyk CS, Culley DJ, et al. American Society for Enhanced Recovery and Perioperative Quality Initiative Joint Consensus Statement on Postoperative Delirium Prevention. Anesth Analg 2020. 130(6): 1572–1590. PubMed

- Evered L, Silbert B, Knopman D, et al. Recommendations for the nomenclature of cognitive change associated with anaesthesia and surgery. Br J Anaesth. 2018. 121(5): 1005–12. PubMed

- Jin Z, Hu J, Ma D. Postoperative delirium: perioperative assessment, risk reduction, and management. Br J Anaesth. 2020. 125(4): 492–504. PubMed

- McSwain JR, Sirianni JM, Wilson SH. Perioperative Considerations for Patients with a Known Diagnosis of Dementia. Adv Anesth. 2021 Dec. 39:113-132. PubMed

Other References

- American Society of Anesthesiologists. Brain Health Initiative. Published 2023. Accessed January 27, 2023. Link

Copyright Information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.