Copy link

Placenta Accreta Spectrum

Last updated: 10/22/2025

Key Points

- Placenta accreta spectrum (PAS) has been increasing over the past few decades, largely due to the rising rate of cesarean deliveries.

- The biggest risk factors are placenta previa and a history of cesarean delivery or other uterine surgery.

- PAS is a major cause of maternal morbidity through hemorrhage.

- An increased number of prior cesarean sections increases the risk of blood transfusion.

Introduction

- PAS is abnormal placenta adherence or invasion to the uterine wall caused by prior uterine surgery, such as cesarean section.

- Abnormal adherence of the placenta can cause catastrophic hemorrhage at the time of delivery, possibly necessitating hysterectomy.

- Safe delivery requires multidisciplinary planning and management.1

Incidence

- The incidence of PAS is increasing due to increased cesarean delivery rate1 and other surgeries that result in scarring.

- 1970s and 80s incidence 1:2500 – 4000

- 1980s to 2000 incidence 1:500

- 2000 to 2010 incidence 1:272

Etiology

- Surgical procedures produce defects in the endometrium and myometrium, which disrupts normal decidual layer development.

- Placental anchoring villi grow abnormally deep and may become inappropriately adherent to the myometrium and neighboring structures.

- Lack of normal anatomical barriers at the site of placental development can result in invasive vascular growth and increased risk of hemorrhage.

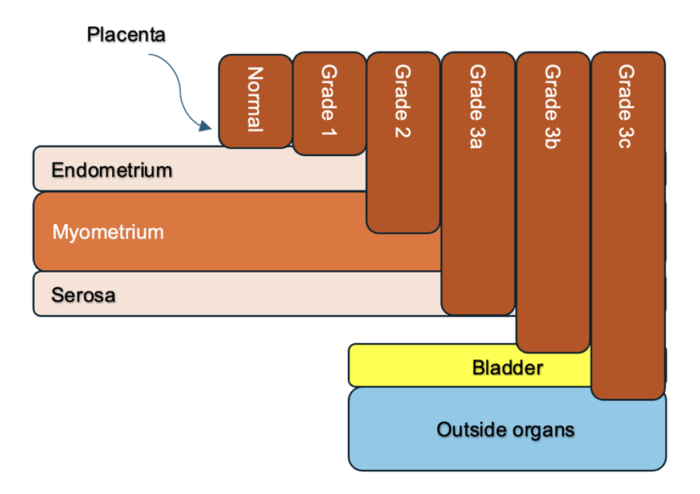

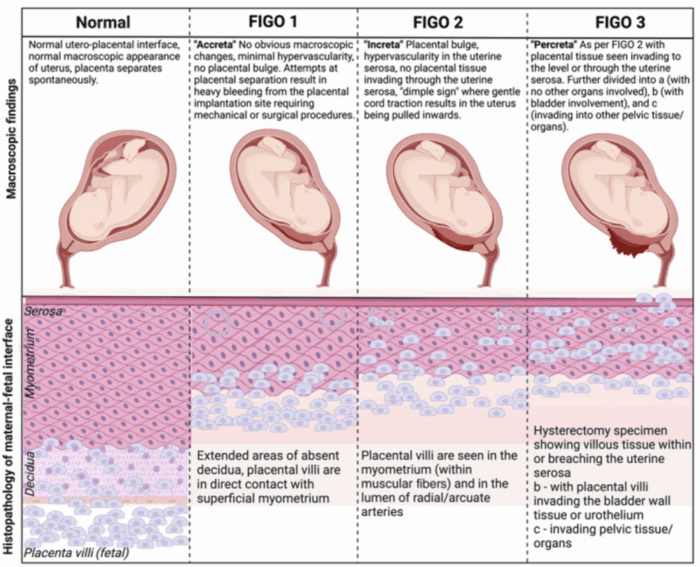

- The Fédération Internationale de Gynécologie et d’Obstétrique (FIGO) Classification: was developed as a tool to clarify terminology in describing the severity of PAS.2 (Figures 1 and 2)

- Grade 1: abnormally adherent placenta (placenta adherent or creta)

- Grade 2: abnormally invasive placenta into the muscle layer (increta)

- Grade 3: abnormally invasive placenta through the entire uterine wall (percreta)

- Grade 3a: limited to the uterine serosa

- Grade 3b: with urinary bladder invasion

- Grade 3c: with invasion of other pelvic tissue/organs

Figure 1. Diagram of Fédération Internationale de Gynécologie et d'Obstétrique (FIGO) classification demonstrating the degree of placental invasion. Image created by authors.

Figure 2. Schematic representation of clinical and histologic criteria of the Fédération Internationale de Gynécologie et d'Obstétrique (FIGO) grading. Source: Bartels HC, et al. Looking back to look forward: Has the time arrived for active management of obstetricians in placenta accreta spectrum? Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2025; 168(1): 48-56. CC BY NC 4.0.

Risk Factors

- The two biggest risk factors are placenta previa and a history of previous cesarean delivery.

- Placenta previa is the single biggest risk factor for PAS.

- Women with placenta previa had a greater than 30 times likelihood of developing PAS.3

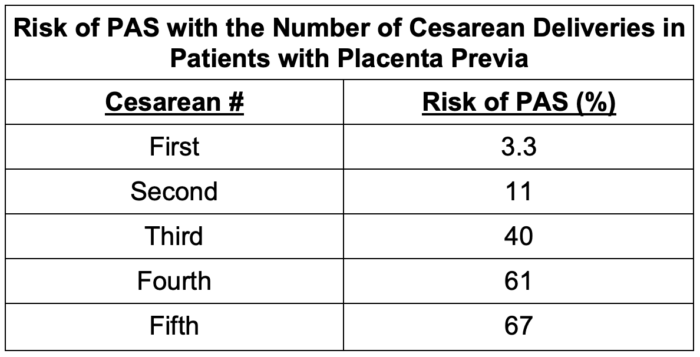

- The risk of PAS also significantly increases in women undergoing their third or greater cesarean delivery.

- The combination of both placenta previa plus a history of previous cesarean delivery dramatically increases the risk of PAS, and this risk increases with the increasing number of previous cesarean deliveries.4

Table 1. Risk of placenta accreta spectrum (PAS) with the number of cesarean deliveries in patients with placenta previa

Obstetric Considerations

Diagnosis

- Clinical risk factors of placenta previa and previous uterine surgery are important.

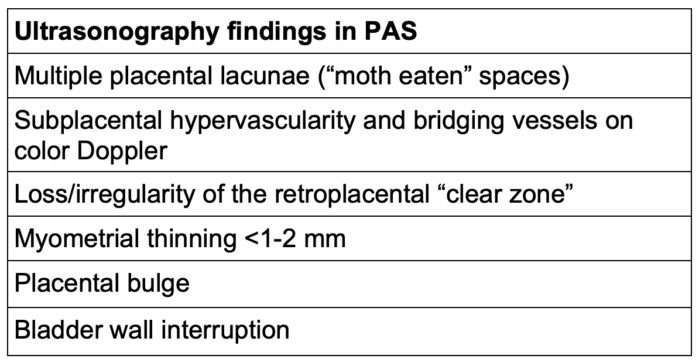

- Ultrasonography (USG) is the primary diagnostic tool for PAS.1 The following are USG findings that can correlate with a diagnosis of PAS:

Table 2. Ultrasonography findings in PAS

- Magnetic resonance imaging is an adjunctive diagnostic tool for evaluating posterior placenta, obesity, or equivocal ultrasound results, but is not recommended for routine use.

- Modalities have varying degrees of sensitivity and specificity.

- Imaging helps anticipate resources but does not reliably stage depth of invasion.

Delivery Timing

- Planned cesarean hysterectomy with placenta left in situ at 34 0/7 – 35 6/7 weeks to optimize fetal maturity and prevent spontaneous labor

- May need to deliver earlier if there is vaginal bleeding or other obstetric concerns

- Transfer of care to a Level III/IV center experienced with PAS is recommended

Surgical Strategy

- Location of surgery: Both the American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology and the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine recommend delivery at level III/IV centers with standardized PAS pathways.1

- A multidisciplinary team, including obstetricians and maternal-fetal medicine specialists (OB/MFM), obstetric anesthesia, gynecological oncology, urology, blood bank, neonatal intensive care unit (ICU), and interventional radiology (IR), must be available.

- Interventional radiology may be involved with prophylactic endovascular balloon placement. The evidence is mixed regarding this, and it is not recommended for routine practice.5

- Urology may assist with cystoscopy and/or ureteral stents when bladder invasion is suspected.

- The default strategy is cesarean hysterectomy with placenta left in situ. Manual attempts at placental removal should be avoided due to the risk of increased bleeding.

- Conservative management/uterus-preserving options are feasible in some cases with carefully selected patients, but do carry a significant risk of bleeding, infection, and emergency reoperation.1

Anesthetic Considerations

Preoperative Considerations

- Multidisciplinary discussions with teams involved (OB/ MFM, neonatal ICU, general surgery, IR, urology, etc.)

- Preoperative clinic evaluation:

- Counsel patient prior to surgery to assess risks and benefits of anesthetic plan

- Assess relevant medical and anesthetic history

- Screen for iron deficiency anemia, optimize hemoglobin preoperatively, and discuss transfusion

- Day of surgery: Obtain a type and screen, and crossmatch necessary blood products

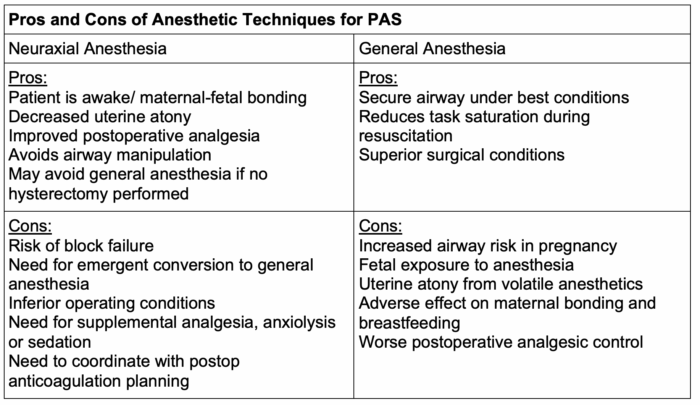

Table 3. Pros and cons of anesthetic techniques for placenta accreta spectrum (PAS)

Intraoperative Considerations

- Currently, there is no one superior anesthetic type for cesarean hysterectomy for PAS.

- General anesthesia, neuraxial anesthesia, or neuraxial anesthesia with planned or unplanned intraoperative conversion to general anesthesia have been utilized for the anesthetic management of cesarean hysterectomy and PAS.

- There is significant variation in practice among different institutions.

- Clinicians should prepare for conversion to general anesthesia if massive hemorrhage occurs or for inadequate surgical blockade.

- For scheduled cesarean hysterectomy, clinicians should consider a combined spinal and epidural with an epidural catheter in situ for flexibility and postoperative pain management. Conversion to general anesthesia with an endotracheal tube is common after the delivery of the fetus.

- Currently, there is no clear consensus on “best management.”

- Retrospective data demonstrated safety with primary neuraxial technique with low conversion rate to general anesthesia.6

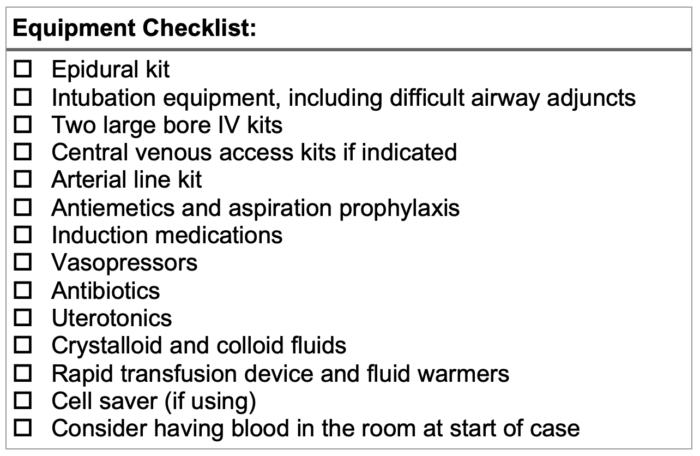

- Monitoring and access considerations:

- Arterial line should be placed preoperatively or prior to incision.

- 2-3 large-bore peripheral intravenous or a central venous catheter if indicated, but not routinely used

- Rapid transfusion devices and fluid warmers should be available.

- Consider cell salvage with a leukocyte-depletion filter, especially in patients who do not consent to allogenic blood products

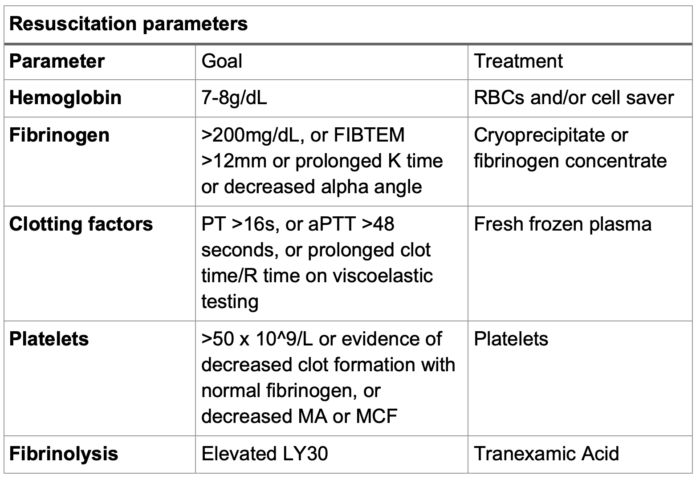

- Transfusion considerations:

- The blood bank must be capable of providing a massive transfusion protocol.

- Resuscitation should occur with goal-directed therapy with viscoelastic testing to reduce the amount of blood products transfused and reduce transfusion-associated complications.7

- Early tranexamic acid administration is recommended.

- Uterotonics for postpartum hemorrhage management should be available until the uterus is surgically managed, but there is no clear consensus for their use in PAS.

Table 4. Resuscitation parameters for PAS. Abbreviations: RBC, red blood cells; FIBTEM, fibrinogen rotational thromboelastometry; PT, prothrombin time; aPTT, activated partial thromboplastin time; MA, maximum amplitude; MCF, maximum clot firmness

Postoperative Considerations

- Postoperative care may occur in the postanesthesia care unit, labor and delivery, or ICU.

- Monitor closely for postoperative bleeding, especially if hysterectomy is delayed.

- Venous thromboembolism prophylaxis: mechanical for all; pharmacologic when bleeding risk is acceptable

- Patients are at elevated risk of thromboembolic disorders, especially if invasive arterial procedures are performed.

- Coordinate timing with neuraxial catheter removal

- There is limited data on the best postoperative analgesia practice for patients with PAS.

- Long-acting neuraxial opioids provide good pain control while limiting systemic side effects.

- Acetaminophen and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs have significant opioid-sparing effects.

- Postoperative epidural analgesia can provide additional pain control.

- Truncal blocks (transversus abdominis plane or quadratus lumborum) can reduce pain following cesarean delivery in the absence of neuraxial morphine.8

Table 5. Equipment checklist for placenta accreta spectrum

References

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists; Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine. Obstetric care consensus No. 7: Placenta accreta spectrum. Obstet Gynecol. 2018;132(6):e259-e275. PubMed

- Jauniaux E, Ayres-de-Campos D, Langhoff-Roos J, Fox KA, Collins S; FIGO placenta accreta diagnosis and management expert consensus panel. FIGO classification for the clinical diagnosis of placenta accreta spectrum disorders. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2019;146(1):20-4. PubMed

- Bowman ZS, Eller AG, Bardsley TR, Greene T, Varner MW, Silver RM. Risk factors for placenta accreta: a large prospective cohort. Am J Perinatol. 2014;31(9):799-804. PubMed

- Silver RM, Landon MB, Rouse DJ, et al. Maternal morbidity associated with multiple repeat cesarean deliveries. Obstet Gynecol. 2006;107(6):1226-32. PubMed

- Iskander R, Massalha M, Remer C, Izhaki I, Salim R. A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials on the effects of internal iliac artery balloon occlusion in placenta previa and placenta accreta spectrum in reducing perioperative bleeding. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2025;170(3):1061-70. PubMed

- Markley JC, Farber MK, Perlman NC, Carusi DA. Neuraxial anesthesia during cesarean delivery for placenta previa with suspected morbidly adherent placenta: A retrospective analysis. Anesth Analg. 2018;127(4):930-8. PubMed

- Warrick CM, Sutton CD, Farber MM, et al. Anesthesia considerations for placenta accreta spectrum. Am J Perinatol. 2023;40(9):980-7. PubMed

- Bollag L, Lim G, Sultan P, et al. Society for Obstetric Anesthesia and Perinatology: Consensus statement and recommendations for enhanced recovery after cesarean. Anesth Analg. 2021;132(5):1362-77. PubMed

Other References

Copyright Information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.