Copy link

Pain Assessment in Neonates

Last updated: 07/31/2023

Key Points

- Neonates do experience pain and have lower thresholds to pain than older patients. They can suffer from both short- and long-term consequences from untreated pain.

- Newborns in the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) frequently undergo painful procedures and interventions.

- Providers should use objective measurements to characterize pain in the neonate and provide an appropriate analgesic regimen.

Introduction

- Pain is characterized as an unpleasant sensory and emotional experience associated with or resembling actual or potential tissue damage.

- While validated clinical scales do exist to measure pain in these preverbal patients, there is no universally used system that is used with consistency in the NICU setting.1

Neurodevelopmental Considerations

- Neonates experience painful stimuli as physiologic, hormonal, and metabolic changes in response to stress as early as the 24th week of gestation.2

- At this age, afferent nociceptive networks have been fully developed.

- This stress response may be greater in preterm infants due to immature descending inhibitory pain pathways.

- The lack of this inhibitory pathway causes hyperalgesia, decreasing the pain and tactile thresholds, ultimately causing greater sensitivity to painful stimuli.

Physiologic and Behavioral Indicators of Pain in Neonates

- Physiologic indicators include changes in vital signs, including heart rate, blood pressure, respiratory rate, and oxygen saturation.2

- These may be the only reliable indices in a patient who is paralyzed, neurologically impaired, or critically ill.

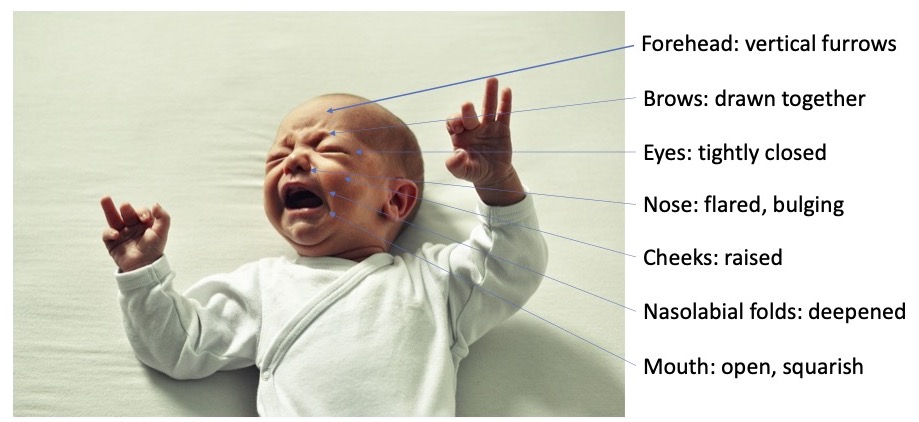

- Behavioral indicators include facial expressions, crying, extremity movement and tone, irritability, and sleeplessness (see Figure 1).

- Preterm infants display similar, but dampened, facial, motor, and physiologic responses to painful stimuli and procedures.

Figure 1. Objective measurements of pain and physical distress in the neonate. Adapted from Wong DL, Hess CS. Wong and Whaley’s Clinical Manual of Pediatric Nursing. 5th Ed. 2000. Mosby, St. Louis.

Pain Assessment Tools in Newborns

- More than 40 different validated neonatal pain assessment tools have been developed.2 Some examples include:

- Premature Infant Pain Profile: Revised (PIPP-R)

- Cries, Requires Oxygen, Increased Vital Signs, Expressions, Sleeplessness (CRIES)

- Neonatal Infant Pain Scale (NIPS)

Neonatal Facial Coding System (NFCS) - Neonatal Pain, Agitation, and Sedation Scale (N-PASS)

- Échelle de la Douleur Inconfort Noveau-Né Scale

- Bernese Pain Scale for Neonates (BPSN)

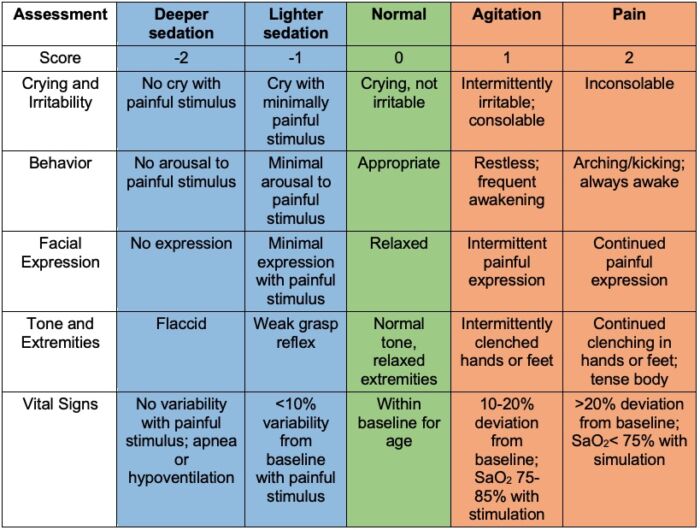

- Of the commonly used neonatal pain tools, two scales (PIPP-R and N-PASS) have metric adjustment for premature infants and only the N-PASS scale (Table 1) includes sedation as part of its scoring system.2,3

- The ideal neonatal pain assessment tool accounts for physiologic measurements, behavioral cues, and gestational age.4

- Further research on objective bio hormonal measurements of pain in the neonate, including heart rate variability, skin conductance, electroencephalography, near-infrared spectroscopy, and serum cortisol levels are under investigation.5

Table 1. N-PASS scoring assessment as an objective measurement of neonatal pain. Scores range from -10 (most sedation) to +10 (most pain) with 0 meaning no sedation. Used with permission from Patricia Hummel, PhD, NNP-BC, Loyola University, Maywood, IL. Link.

Short-Term Consequences of Neonatal Pain

- As preterm infants are in a window of intense neurological maturation with immature sensory processing and inhibition controls, pain responses are in fact exaggerated during this time.

- Neonatal rodent models support the association between painful procedures and altered behavioral development, including negatively altered locomotor activity. withdrawal/defensive as well as depressive/anxious behavior, and reduced social activity.6

- For example, full-term infants who undergo circumcision without analgesia display increased pain responses to immunization at 4-6 months when compared to infants who undergo circumcision with analgesia.

Long-Term Consequences of Neonatal Pain

- Preterm infants are vulnerable to permanent changes in cerebral development and processing, including altered pain sensitivity and maladaptive responses to pain later in life.1

- While many factors contribute to altered pain perception in the neonate, including birth weight, confounding neonatal illness, and socioeconomic status, current beliefs are that repetitive painful stimuli in the NICU environment have the potential to create lasting, deleterious behavioral effects which have been objectively studied by measuring speed of behavioral dampening in objective pain measurements and resting basal heart rate.

- Chronic pain states can cause a systemic “rewiring” of nociceptive neuronal pathways in the central and peripheral nervous system; unmanaged neonatal pain states are believed to potentially cause similar responses in the body.

- Preterm infants who experienced pain as a neonate have higher rates of internalizing behaviors than full-term children.6

References

- Anand KJ, Hickey PR. Pain and its effects in the human neonate and fetus. N Engl J Med. 1987;317(21):1321-9. PubMed

- Maxwell LG, Fraga MV, Malavolta CP. Assessment of pain in the newborn: An update. Clin Perinatol. 2019;46(4):693-707. PubMed

- Hummel P, Puchalski M, Creech SD, et al. Clinical reliability and validity of the N-PASS: neonatal pain, agitation and sedation scale with prolonged pain. J Perinatol. 2008; 28(1): 55-60. PubMed

- Vecchione TM, Agarwal R, Monitto CL. Error traps in acute pain management in children. Paediatr Anaesth. 2022;32(9):982-92. PubMed

- Cong X, McGrath JM, Cusson RM, et al. Pain assessment and measurement in neonates: an updated review. Adv Neonatal Care. 2013;13(6):379-95. PubMed

- Zuke JT, Rice M, Rudlong J, et al. The effects of acute neonatal pain on expression of corticotropin-releasing hormone and juvenile anxiety in a rodent model. eNeuro. 2019 ;6(6): ENEURO.0162-19.2019. PubMed

Copyright Information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.