Copy link

Overview of Pediatric Neuraxial Blockade

Last updated: 01/19/2024

Key Points

- Neuraxial anesthesia can be used as a sole anesthetic or as an adjunct to sedation or general anesthesia.

- Spinal anesthesia is a safe alternative to general anesthesia in neonates and former premature infants at risk for postoperative apnea, as well as in resource-limited settings.

- Epidural anesthesia may facilitate early tracheal extubation in neonates and is a useful adjunct to multimodal analgesia to spare opioids and enhance recovery in the postoperative period.

Indications and Advantages1

- Neonatal spinals and single-shot caudal anesthetics are effective for lower abdominal, urological, and lower extremity surgeries.

- Lumbar and thoracic epidural infusions via a catheter can provide analgesia for chest and upper abdominal procedures.

Caudal

- Provides analgesia for surgical procedures below the umbilicus

- Reduces intraoperative anesthetic requirements and postoperative opioid requirements

Epidurals

- Effective for extensive thoracic, intraabdominal/pelvic, and lower extremity orthopedic procedures

- Potential to reduce the surgical stress response and release of catecholamines2

- Decreases anesthetic requirements intraoperatively and improves ventilation postoperatively

- Postoperative epidural infusions of local anesthetics and opioids reduce the use of intravenous opioids and related side effects, such as nausea, vomiting, ileus, and respiratory depression.2

- Risk reduction in patients with known or positive family history of malignant hyperthermia and patients with neuromuscular disorders who have restricted cardiopulmonary function2

Spinal

- It can be used for inguinal, urological, and lower extremity surgeries.

- Avoids manipulation of the airway and interference with spontaneous ventilation, especially in neonates with preexisting respiratory impairment and increased airway reactivity3

- Provides cardiovascular stability and reduces the need for postoperative ventilation3

- Spinal blocks in neonates and infants with plain bupivacaine typically provide surgical anesthesia for 45–60 min.

- With the addition of an adjunct or in combination with a caudal anesthetic, the block duration of a spinal can be extended to accommodate longer surgeries.

Contraindications2

Absolute Contraindications

- Presence of local infection at the needle insertion site

- Uncorrected hypovolemia or hemodynamic instability

- Increased intracranial pressures

- Allergy to the intended local anesthetic

- Parent or child refusal

Relative Contraindications

- Inherited or acquired coagulation abnormalities due to risk for epidural hematoma (e.g., hemophilia, patients receiving warfarin or heparin, etc.)

- Presence of systemic infection

- Anatomic abnormalities such as spina bifida or tethered cord

- Progressive neurologic disorders

- Stenotic valvular heart lesions

Anatomical and Physiological Considerations

- There are several anatomical and physiological considerations for neuraxial anesthesia in infants and children.

- Thoracic spinous processes are less caudally angulated in infants.3

- The conus medullaris extends to L4 in premature infants and L3 in a term neonate. By 1 year of age, the conus medullaris is nearer its adult location at L1. Therefore, spinal anesthesia in neonates and infants should be performed at the L4-L5 or L5-S1 levels.2

- The dural sac extends lower in premature babies and neonates (around S4), and by 2 years of age, it ascends to its adult location at S2.3

- The absence of thoracic kyphosis in infants means greater cephalad spread of injected drugs, extending the dermatomal coverage of a central neuraxial block.

- Cerebrospinal fluid volume is approximately 10 mL/kg in neonates, 4 mL/kg in infants and toddlers, and 2 mL/kg in older children and adults. This necessitates a larger spinal dose in neonates and infants.2

- The vascularity of the pia mater combined with greater cardiac output leads to faster local anesthetic (LA) reabsorption, and thus, shorter block duration.

- The distance from the skin to epidural space is about 5-12 mm in infants younger than 6 months. From 6 months to 10 years, the distance is approximately 1 mm/kg.2

- The ligamentum flavum in younger children is thinner and yields a subtler loss of resistance during epidural placement. A more compliant epidural space eases the insertion of an epidural catheter.2

- As a result of the immature sympathetic autonomic nervous system in infants, chemical sympathectomy from central neuraxial anesthesia does not result in vasoplegia, hypotension, or cardiovascular instability, sometimes seen in adults.

Techniques2

Caudal

- Positioning: The child is placed in the lateral decubitus position with the knees pulled up toward the chest.

- Landmarks: Bilateral posterior superior iliac spines and the sacral hiatus (SH) should form an equilateral triangle. The SH is bounded by the sacral cornua, which are palpable on either side of the midline, about 1 cm apart.

- Technique: After sterile preparation, a 22- or 25-gauge needle is inserted at a 70° angle to the skin over the SH. A pop will be felt as the needle passes through the sacrococcygeal membrane. Once the sacrococcygeal membrane is pierced, the needle angle is dropped to 20° to 40° from the skin and advanced by 2 to 4 mm. A stimulating needle can also be used. If the stimulating needle is in the caudal space, anal sphincter activity will be visible with a stimulation of 1 to 10 mA. If a stimulating needle is used, it should not be advanced greater than 2 to 4 mm past the sacrococcygeal membrane.

- Ultrasound-guided technique: An ultrasound probe is placed in a transverse orientation just above the gluteal cleft. Scanning cephalad allows identification of the sacral cornua and sacral hiatus. Then the transducer is turned longitudinally to identify the sacral canal and sacrococcygeal ligament. Please see the OA summary on caudal anesthesia in children for more details. Link

- Before administering the local anesthetic, the needle should be aspirated to detect inadvertent subarachnoid or intravascular injection.

- Local anesthetic volume: The drug dose for coverage up to a certain dermatomal level depends on the volume of the local anesthetic (not the concentration) and the capacitance of the epidural space, which varies inversely with age.

- According to the classic Armitage formula, a volume of 0.5 mL/kg local anesthetic results in a lumbosacral block, 1 mL/kg results in a thoracolumbar block (T10 block), and 1.25 mL/kg results in a mid-thoracic block.4

- Local anesthetic choice: Bupivacaine (0.25% or 0.125%, with or without epinephrine) or ropivacaine (0.2%) are the most commonly used local anesthetic blocks for single-shot caudal blocks.

- The maximum dose of local anesthetic for a single-shot caudal is as follows:5

- Bupivacaine or levobupivacaine- 2.5 mg/kg

- Ropivacaine- 2 mg/kg

Epidural

- Positioning: The child is placed in the lateral decubitus position with the knees pulled up toward the chest.

- Technique: Epidural anesthesia is typically performed at the lumbar or thoracic levels and the epidural space is accessed via a midline or paramedian approach. In the midline approach, an appropriately sized Tuohy or Crawford needle is inserted in the midline between the spinous processes until loss of resistance is achieved. In the paramedian approach, the epidural needle is inserted lateral to the superior edge of the spinous process and “walked off” the lamina to access the epidural space.2

- Loss of resistance to saline is the preferred technique in children because of the risk of venous air embolism from the injection of air into the epidural veins.

- As mentioned previously, the distance from the skin to the epidural space is about 5-12 mm in infants younger than 6 months. In patients weighing 10- 25 kg, the distance is approximately 1 mm/kg. In children weighing more than 25 kg, the distance is calculated as 0.8 + (0.05 × wt [kg]).

- Catheters can frequently be threaded from the lumbar to the thoracic level with the Tuohy bevel directed cephalad. The epidural catheter tip is ideally placed at a vertebral level that corresponds to surgical dermatomes.2

- T4 (nipple line) for thoracic surgeries

- T7 (lower edge of scapula) for upper abdominal surgeries

- T10 (umbilicus) for lower abdominal surgeries

- L1 (inguinal crease) for lower extremity surgeries

- The routine administration of a test dose for epidural catheters in infants and children is controversial because of the low sensitivity and specificity under general anesthesia.2 If a test dose is administered, 0.1 mL/kg of 1.5% lidocaine with epinephrine (1 in 200,000) is commonly used.

- An increase in heart rate of 10 beats per minute or higher or an increase in systolic blood pressure of 15 mmHg or higher above the baseline within 90 seconds of a test dose injection is indicative of intravascular injection.2

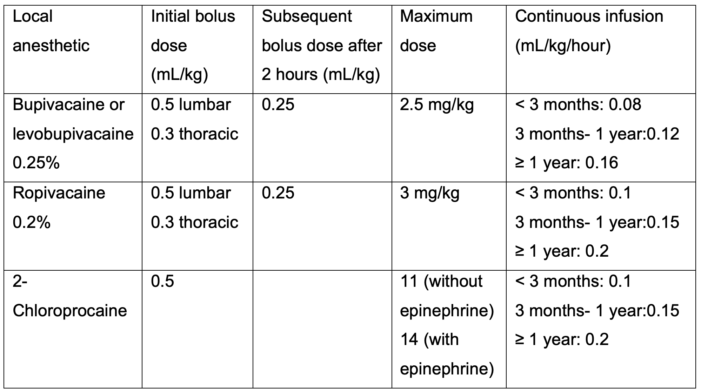

- The initial loading dose, maximum dose, and recommended dosage for continuous epidural infusion of local anesthetics are listed in Table 1.2,5

- Amide local anesthetic can accumulate in infants and young children because of immature hepatic metabolism and low plasma levels of alpha-1 acid glycoprotein. Therefore, an ester local anesthetic (2-Chlorprocaine) is preferred in this age group as it is metabolized by pseudocholinesterase.2

Spinal

- Positioning: The patient is positioned in the lateral or sitting position. The spine is flexed into a C-shape while the head is extended to ensure a patent airway. An assistant should help with positioning and airway management.

- Landmarks: The Tuffier’s line is at the level of L4/L5 or L5/S1 interspace.

- Technique: Pediatric spinal needles (25G, 25 mm) are preferred to adult needles. Pencil-tip needles are not used in infants. The spinal needle with a stylet is advanced in the midline at the L4/L5 or L5/S1 interspace until a “pop” is felt.

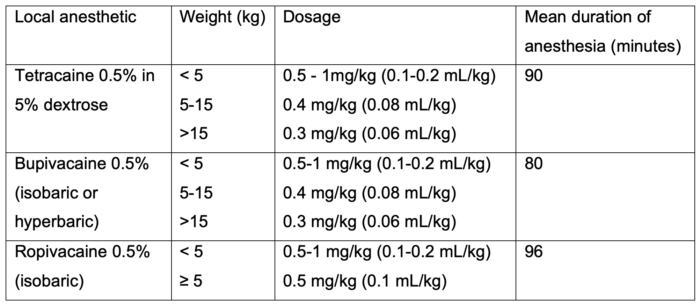

- The dosing of local anesthetics for spinal anesthesia in children is listed in Table 2.

- The baricity of the local anesthetic and the patient’s position during the spinal block affects the desired anesthetic height achieved. Hyperbaric local anesthetics can result in a “saddle” blockade, while a hypobaric local anesthetic spreads in the opposite direction to gravity. On the other hand, isobaric local anesthetics concentrate at the site of injection.2

- Please see the OA summary on spinal anesthesia in neonates and infants for more details. Link

Adjuvants

- Additives, such as clonidine and dexmedetomidine, may be added to the local anesthetic to prolong the duration and density of single injection blocks, although concern still exists regarding systemic adverse effects, such as arterial hypotension, bradycardia, sedation, and delayed discharge1

- Clonidine (1-2 mcg/kg) and preservative-free morphine (10-30 mcg/kg) can be added to the local anesthetic to prolong the duration of spinal blockade.5

- Similarly, clonidine and dexmedetomidine have been used to prolong postoperative analgesia when used as an adjunct in caudal blocks.5

References

- Lang RS, Hall-Burton D, Praslick A, Flack S. Regional anesthesia. In: Davis PJ, Cladis FP (eds). Smith’s Anesthesia for Infants and Children. Tenth edition. Philadelphia, PA. Elsevier; 2022. 519-77.

- Koszela KB, Sethna N, Pediatric Neuraxial anesthesia and analgesia. Update in anaesthesia. 2021; Volume 35: World Federation of Societies of Anesthesiologists. Link

- Greaney D, Everett T. Paediatric regional anaesthesia: updates in central neuraxial techniques and thoracic and abdominal blocks. BJA Educ. 2019;19(4):126-34. PubMed

- Armitage EN. Is there a place for regional anesthesia in pediatrics? Yes! Act Anasethesiol Belg. 1988:39:151-6. PubMed

- Suresh S, Ecoffey C, Bosenberg A, et al. The European Society for Regional Anaesthesia and Pain Therapy/American Society of Regional Anesthesia and Pain Medicine recommendations on local anesthetics and adjuvant dosage in pediatric regional anesthesia. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2018;43(2). PubMed

Copyright Information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.