Copy link

Needle Stick Injuries: Prevention and Management

Last updated: 09/30/2025

Key Points

- Needles pose the threat of accidental needle stick injuries (NSIs), yet using needles is obligatory for specific procedures and required for the administration of some medications by anesthesia professionals.

- NSIs can introduce pathogens that may cause harm to the anesthesia professional.

- There are evidence-based measures to follow that will reduce physical and psychological harm for the anesthesia professional who experiences a needle stick injury.

- Safety devices, needleless systems, and caution by the anesthesia professional reduce the likelihood of an NSI.

Introduction

- NSIs are an occupational hazard for anesthesia professionals. The use of needles is unavoidable in requisite procedures such as:

- Drawing blood

- Cannulating arteries and veins

- Epidural, intrathecal, and regional administration of medications

- Intraosseous, intramuscular, and subcutaneous administration of medications

- Serious health consequences can arise from NSIs

- Physical consequences2

- Local site infection (including staphylococcal and streptococcal), leading to cellulitis

- Blood-borne infections, including hepatitis B virus (HBV), hepatitis C virus (HCV), and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV).

- Psychological consequences1

- Unavoidable use of needles causes underlying workplace stress

- Anxiety related to potential consequences from an NSI

- Physical consequences2

- NSIs cost time and money to report, to get tested, and to receive treatment

- It is estimated that between 30% and 50% of NSIs go unreported to the appropriate department (Infectious Disease, Employee Health, etc.) or supervisor.1,2

- Estimates show a high prevalence of NSIs among anesthesia professionals

- Occurrence of 32,266 per year (more than 88 needle sticks per day)5

- More than 1 in 4 anesthesia professionals incur an NSI each year

Risk Factors

- An NSI is almost always related to a breach in proper procedure when:1,2

- Institutional protocol is not followed, is not taught, or does not exist

- Appropriate equipment is not available, such as needleless devices, needles with safety devices, or sharps containers

- Risk factors that increase the likelihood of NSIs in anesthesia professionals include work-related stress, sleep deprivation, cognitive overload, and fast-paced care.1-4

- Additionally, the risk of NSIs for anesthesia professionals is highest for individuals with fewer years of experience, particularly those involved in direct patient care.

- Anesthesia fellows have the highest incidence (14.3-50%), followed by postgraduate year 2 physician anesthesia residents (13.5-39%).2,4

- Supervising physicians with experience are the least likely to experience an NSI (2.1%).4

- Activities like withdrawing blood and administering blood are associated with the highest incidence of exposure to infection, as the likelihood of pathogen transmission is highest with a blood-contaminated hollow-bore needle.1-4

Reporting and Managing Injuries

- Each institution/facility should have established policies and procedures for guidance following NSIs, such as those outlined below.

- Reporting the injury involves contacting the facility’s infectious disease department for immediate consultation and providing the following information:

- Patient’s history

- Full medical history, including vaccination history

- Prior exposure to bodily fluids and treatment, if any

- History of drug use, piercings, sexual behavior, blood transfusions, and hemodialysis

- Any travel outside of the country within the last 12 months

- Professional’s vaccination history

- Patient’s history

- In addition to reporting, the anesthesia professional should:

- The area should be cleaned with soap and water or saline.

- Caustic agents (e.g., bleach) should not be applied to the wound. The use of topical antiseptics and/or expressing fluid by squeezing the wound has not been shown to reduce the risk of transmission.

- Immediate emergency care should be obtained to determine if further treatment of the injury site is necessary and to determine next steps, including testing of both the patient and the injured professional.

- Report to the emergency department or occupational health and safety clinic within 72 hours

- Alert the supervisor, who should address the mental stress of the exposure, even if there is no infection

- Seek an employee assistance program or other counseling to reduce anxiety related to the NSI

- Test the patient’s blood and the professional’s clinician’s blood for HIV, HBV, and HCV.1

- Early testing of both the patient and the anesthesia professional increases the likelihood that the professional will obtain early treatment.

- If the patient’s blood is positive for a transmissible illness, Table 1 lists the management of the anesthesia professional following the NSI.

- Follow the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) and Prevention guidelines for postexposure management.

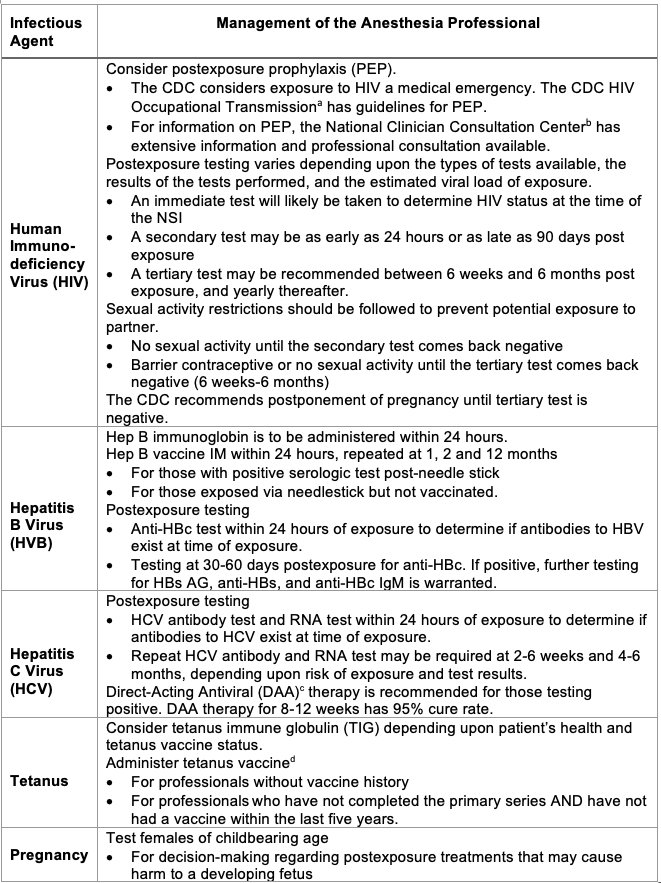

Table 1. Recommendations following NSI from a patient with positive transmissible illness.1,5,6

aU.S. Centers For Disease Control and Prevention. HIV Occupational Transmission. CDC. Published September 23, 2024. Accessed October 1, 2025. Link

bNational Clinician Consultation Center. PEP: Post-Exposure Prophylaxis. Accessed October 1, 2025. Link

cU.S. Centers For Disease Control and Prevention. Clinical Care of Hepatitis C. CDC. Published January 31, 2025. Accessed October 1, 2025. Link

dU.S. Centers For Disease Control and Prevention. Clinical Guidance for Wound Management to Prevent Tetanus. CDC. Published June 10, 2025. Accessed October 1, 2025. Link

Prevention

- Effective strategies for prevention of NSIs include:

- Educational programs implemented by occupational education, health and safety, or infectious disease.

- These programs monitor exposures, identify high-risk procedures, and encourage best practices to reduce or eliminate NSIs and exposure.4

- Education should include the types of possible NSIs, the risks of NSIs, and the risks of transmission of pathogens related to NSIs

- Developing facility guidelines to prevent injuries and infections from needle sticks.2,4,5

- Best practice for prevention of NSIs

- Routine training for proper handling of needles is effective at reducing the incidence of self-injury and exposure.4 Routine training includes:

- Proper recapping or no recapping of needles (follow specific facility recommendations)

- Proper disposal of needles in a sharps container as soon after use as possible

- How to use the safety devices on needles equipped with safety devices

- How to dispose of needles if no sharps container is available

- Announce to staff nearby when a needle is being transferred from the patient’s bedside to a distant sharps container

- Review of work hours and overtime policy restrictions to prevent fatigue.

- Reduction of exposure to sharps1

- Only use needles when necessary

- When drawing blood samples

- When cannulating arteries or veins

- For epidural, intrathecal, and regional administration of medications

- For intraosseous, intramuscular, and subcutaneous injections of medications

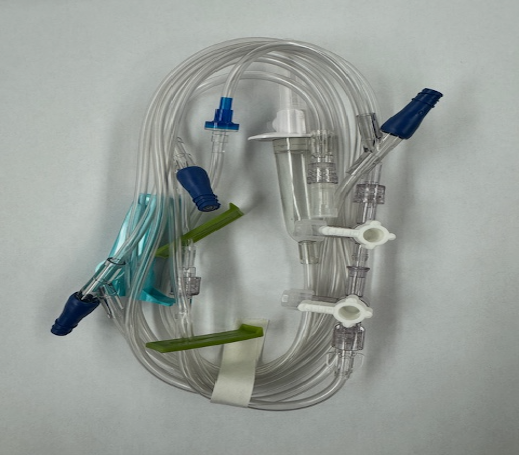

- Utilize needleless systems whenever possible (Figure 1)

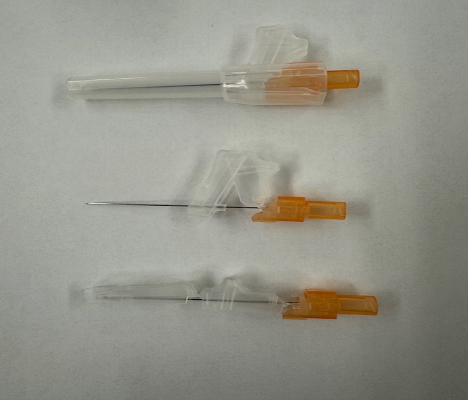

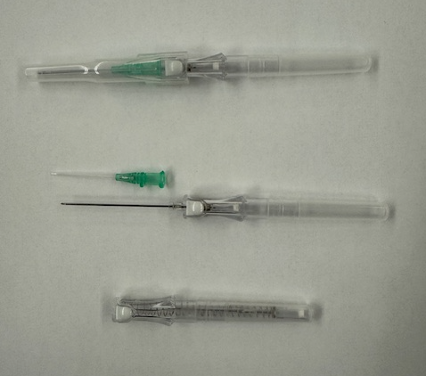

- Use needles with safety devices whenever possible (Figure 2; Figure 3)

- Routine training for proper handling of needles is effective at reducing the incidence of self-injury and exposure.4 Routine training includes:

Figure 1. Needless intravenous tubing system.

Note the blue needleless hubs and white Luer-lock capped hubs. Luer-lock syringes twist onto hubs for administration of intravenous medications. The white hub [capped] on the drip chamber is considered sharp when uncapped and removed from the infusion bag.

Figure 2. Needle safety device

Top: Capped needle prior to use. Middle: Uncapped needle during use. Note the ability of the clear plastic sheath to slide over needle after use. Bottom: Needle with safety device deployed over tip, locked in place.

Figure 3. Safety intravenous cannulation catheter

Top: catheter before insertion. Middle: catheter showing cannula (with green hub) and introducer needle removed from cannula. Bottom: Needle retracted into safety device after the white button is pushed.

References

- King KC, Strony R. Needlestick. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; [Updated 2023 May 1]. Accessed 2025 June 18. Link

- Zbeidy R, Livingstone J, Shatz V, et al. Occurrence and outcome of blood-contaminated percutaneous injuries among anesthesia practitioners: A cross-sectional study. International J Qual Health Care. 2022; 34(1):1-5. PubMed

- Reddy S, Joseph V, Liu Z, Straker T. Characteristics of sharp injuries in anaesthesia providers in New York State: A cross-sectional study. J Clin Diagn Res. 2018;12(12). Link

- Borna R, Rahimian R, Natalie Koons BS, et al. Needlestick injuries among anesthesia providers from a large US academic center: A 10-year retrospective analysis. J Clin Anesth. 2022; 80:110885. PubMed

- Sharps Safety Program Resources. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2024. Accessed 2025 July 6. Link

- Clinical Guidance for PEP. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2025. Accessed 2025 August 16. Link

Copyright Information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.