Copy link

Maxillofacial Trauma and Neck Injuries

Last updated: 01/17/2023

Key Points

- Maxillofacial trauma has the potential for direct trauma to the airway, and these injuries are often dynamic, and conditions can deteriorate quickly. The first step is to determine if the airway needs to be secured and if it needs to be done immediately or urgently.

- The airway must be secured early when there are signs of active or impending airway obstruction. A “double setup” with simultaneous preparation for orotracheal intubation using rapid sequence intubation (RSI) and cricothyrotomy facilitates the most efficient way to secure the airway quickly.

Introduction

- Traumatic airway injuries are rare (incidence less than 1%) but are associated with high mortality.1

- Airway injuries can be divided into three types: maxillofacial, neck, and laryngeal injuries.

- Trauma to the face and neck may cause life-threatening injuries to the upper airway, major vascular structures, cervical spine, and aerodigestive tract.2 The goal of airway management in such cases is to relieve or prevent airway obstruction and to secure the unprotected airway from aspiration.

Maxillofacial Trauma

Introduction

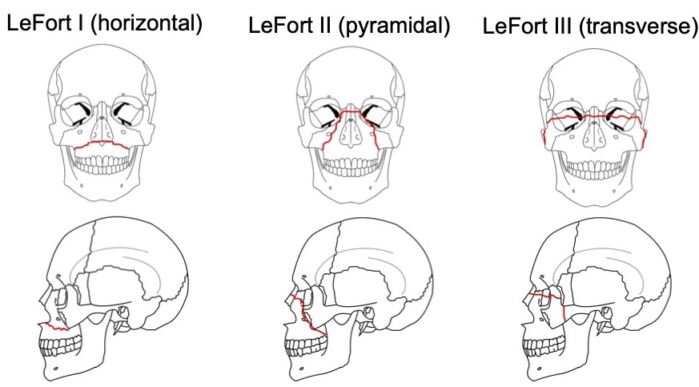

- Blunt or penetrating maxillofacial trauma can result in a wide range of injuries, including mandibular, maxillary, zygomatic, orbital floor, and basilar skull fractures. The Le Fort fractures are a pattern of mid-face fractures characterized by fractures of the pterygoid plates (Figure 1)1. Le Fort I fractures are horizontal fractures above the maxillary alveolar process, resulting in a floating palate. Le Fort II fractures are pyramidal in shape and also include the inferior orbital rim. Le Fort III fractures separate the facial bones from the rest of the skull. Le Fort II and III fractures may be associated with basilar skull fractures and leakage of cerebrospinal fluid.1 Basilar skull fractures may result in “raccoon eyes” (periorbital ecchymosis) or Battle’s sign (retro auricular ecchymosis).1

Figure 1. Le Fort fractures. Source: Wikipedia. I, RosarioVanTulpe, CC BY- SA 3.0

- Blunt or penetrating maxillofacial injury can also cause direct airway trauma. Such traumatic injuries can cause severe bleeding into the oropharynx, expanding hematomas within soft tissue, and disruption of bone and soft tissue. These types of traumatic injuries are dynamic, and conditions can deteriorate quickly. For example, hematomas and soft-tissue swelling can rapidly expand and convert a partially obstructed airway into a completely obstructed airway.

Airway Assessment1,3

- In patients with maxillofacial trauma, the anesthesiologist must rapidly assess the patient’s airway to determine if an emergent definitive airway is needed.

- Direct signs of airway compromise include dyspnea and stridor.3

- Indirect signs of airway compromise include drooling, trismus, odynophagia, tracheal deviation or anatomical abnormality of the larynx or trachea.3

- The trauma and anesthesiology teams must also be vigilant for signs of developing airway compromise, such as severe bleeding in the oropharynx or nasopharynx, crepitus in the neck or chest, hematoma in the neck or lower face, hoarseness or changes in voice, subjective sense of dyspnea despite adequate oxygen saturation.

- Patients with unstable mandible or midface injuries may appear stable initially but are at a high risk of progressing to an unstable and potentially difficult airway. Similarly, patients with bleeding into the oropharynx or nasopharynx and a fluctuation or worsening level of consciousness are also at high risk of progressing to an unstable and potentially difficult airway.3

- Severe maxillofacial injuries that disrupt bones and create instability in the middle or lower face make it difficult to maintain a proper mask seal and cause difficulty with bag-mask ventilation (BMV). Airway obstruction from heavy bleeding, soft tissue swelling or hematoma from maxillofacial injuries, and subcutaneous emphysema can also cause difficulty with bag-mask ventilation.

- Laryngoscopy and intubation are likely to be extremely difficult when there is significant bleeding or disruption of normal anatomy. It is essential to have effective suction available to clear bleeding and debris that may obscure the glottic view during laryngoscopy.

- Maxillofacial injuries may limit mouth opening or present with debris such as teeth or bone fragments in the oropharynx and make the use of rescue devices such as laryngeal mask airways difficult to impossible.

- Airway disruption or distortion due to swelling or hematomas can cause normal anatomical relationships to be obscured and make cricothyrotomy difficult as well.

Airway Management1,3

- Initially, 100% oxygen is administered, and the airway is cleared of debris such as dentures, loose teeth, tissue, blood, and vomitus. This is followed by basic maneuvers such as suction, chin lift, jaw thrust, oral airway placement, and BMV if these procedures are not contraindicated based on the mechanism of injury.1

- In patients with facial fractures, extreme care must be taken with BMV as it may displace facial bone fragments, worsen airway obstruction, and worsen subcutaneous emphysema, pneumocephalus, pneumomediastinum, and pneumothorax. However, in some patients with facial fractures, BMV may improve the situation as the face mask may act as a splint to stabilize the fractures.

- It is prudent to secure the airway early in patients exhibiting any signs or symptoms listed above, as they are at high risk for rapid deterioration. It is also best to secure the airway early when the extent of injuries or their likely course is unknown.

• There may be time to weigh different approaches and prepare for securing the airway if the SpO2 can be maintained above 90%. If the patient has normal vital signs, pulse oximetry, and mental status and does not exhibit the signs of impending airway compromise listed above, the patient may be observed. - A definitive airway must be quickly established if adequate oxygenation cannot be maintained.

- If difficulty with BMV is not anticipated, a standard RSI may be used to secure the airway.

- If difficulty with BMV is anticipated, an awake intubation may be the best approach to secure the airway. Sedation with propofol or ketamine, along with topical airway anesthesia with atomized/nebulized lidocaine or lidocaine paste/jelly allows the patient to continue to breathe spontaneously while allowing to overcome the patient’s protective airway reflexes. The awake and sedated patient can undergo direct laryngoscopy, video laryngoscopy or fiberoptic laryngoscopy. If there is significant bleeding within the airway, flexible fiberoptic laryngoscopy may be difficult to impossible. If vocal cords are visible, intubation may be performed during the awake look or the laryngoscopy. A standard RSI may also be performed after removing the laryngoscope at the risk of the glottic view deteriorating in the interim if the maxillofacial injuries lead to worsening of the airway with time.

- An alternate approach is to use a “double setup” where simultaneous preparation for orotracheal intubation and cricothyrotomy is undertaken. This allows for RSI with one or two brief attempts at laryngoscopy and proceeding directly to cricothyrotomy if intubation is not possible.

- In case of severe maxillofacial injuries, there may be an obstruction or an anatomic disruption that may prevent access to the glottis, and orotracheal intubation will be impossible. In such a scenario, a surgical airway may be the first and only choice to secure the airway. A surgical airway is also necessary in patients with trauma to the airway that have a SpO2 below 90% despite optimal BMV or in whom BMV cannot be performed.

- In patients who can be effectively oxygenated with BMV, supraglottic airway devices may be used as rescue devices if there is no supraglottic airway obstruction or distortion of airway anatomy.

Neck Injuries1,4

- Penetrating and blunt neck trauma has the potential to involve almost every major vital structure in the respiratory, vascular, digestive, endocrine, and neurologic organ systems.

- Penetrating neck injuries are caused by gunshot, knife, or other sharp foreign bodies. Blunt neck injuries are caused by three mechanisms:1,2

- Direct blow to the neck such as from collision with dashboard, steering wheel, bicycle handlebars, clothesline injury, human assault, sports injury, fall from height, hanging, etc.

- Deceleration injuries, such as car accidents or falls, can cause shearing injuries to fixed structures, such as cricoid cartilage and tracheal carina

- Increased pressures, such as sudden anterior-posterior chest compression against a closed glottis, causes transmission of the increased intrathoracic pressure to the neck.

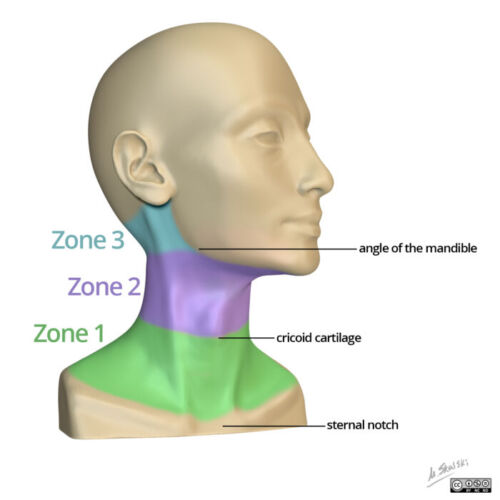

- Dividing the neck into three zones helps with the differential diagnosis and guides airway management, hemorrhage control, and surgical approach (Figure 2).1,4

Figure 2. Zones of the neck. Case courtesy of Dr. Matt Skalski, Radiopaedia.org, rID: 44651.

Zone 1 extends from the clavicles to the inferior border of the cricoid cartilage and is a high-risk zone due to the presence of the trachea, lungs, and great vessels.1 Mortality risk is highest with zone 1 injuries as they typically involve the major vessels, lungs, trachea, and esophagus.5

Zone 2 extends from the cricoid cartilage to the angle of the mandible. It is the most frequently injured zone, but surgical access is easier. It is also easier to control hemorrhage in zone 2 as the great vessels are not anchored to adjoining structures.1

Zone 3 extends from the angle of the mandible to the skull base and is also a high-risk zone due to the difficulty of surgical access.1

- Patients with a penetrating neck injury may show signs and symptoms that necessitate immediate attention and stabilization of the airway. These include respiratory distress, severe hemorrhage or neck hematoma, hemoptysis, subcutaneous emphysema, stridor, distorted neck anatomy, bruit, or thrill, extensive or sucking neck wound, difficulty or pain when swallowing, abnormal or hoarse voice, and shock.

- In patients with a penetrating neck injury, BMV should be performed with vigilance and in a gentle manner, as it may force air into injured tissue planes and distort airway anatomy.

- In patients requiring stabilization of the airway, if the anatomic structures and relationships of the airway are preserved, RSI is appropriate to secure the airway.

- If there is any distortion of the anatomic landmarks or an obstruction above the larynx making effective ventilation or placement of a tracheal tube unlikely, a surgical airway is necessary. Massive hemoptysis or hematemesis may also necessitate a surgical airway.

- When a penetrating neck injury causes partial or complete transection and exposure of the trachea, there may be frothing or large air bubbles visible in the neck wound. In such cases, the caudad portion of the exposed trachea can be stabilized with a clamp and intubated directly.

- If the patient is initially stable, but a difficult airway is anticipated due to distorted anatomy, an “awake look” approach may be appropriate. Light sedation and topical anesthesia of the airway are used to enable direct or fiberoptic laryngoscopy, and if conditions are favorable, intubation is performed.

- In case of subcutaneous emphysema in the neck, a direct airway injury is suspected, and fiberoptic guided oral intubation allows determination of the integrity of the interior of the airway.

- A “double setup” with simultaneous preparation for RSI and a surgical airway is also appropriate in patients with a penetrating neck injury as preparation for unanticipated difficulty with securing the airway.

- While cricothyrotomy is the main method of establishing a surgical airway, it may be difficult in a patient with a penetrating neck injury with distorted neck anatomy. Cricothyrotomy is relatively contraindicated if there is an anterior neck hematoma or if a laryngeal injury is suspected.

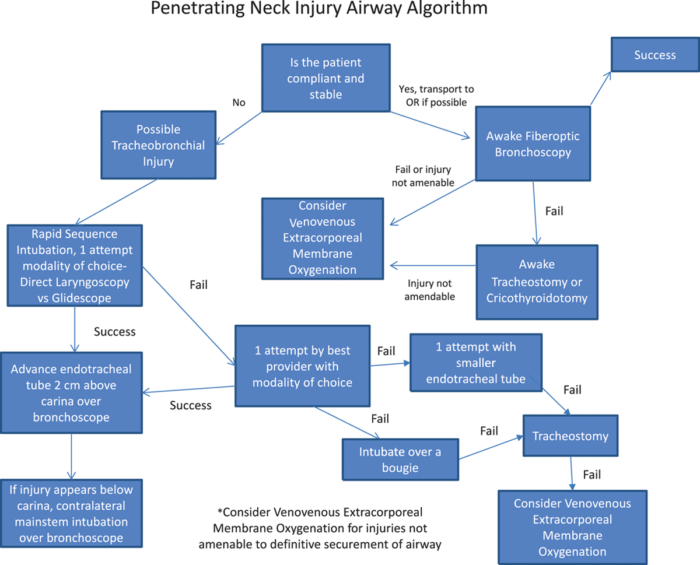

- Figure 3 shows an algorithmic approach to securing the airway in penetrating neck injuries.

Figure 3. Penetrating neck injury airway algorithm. Reproduced with permission from Johnson AM, et al. Airway management in a patient with tracheal disruption due to penetrating neck trauma with hollow point ammunition: A case report. AA Pract. 2018; 10(9): 242-5.5

References

- Jain U, McCunn M, Smith CE, et al. Management of the traumatized airway. Anesthesiology. 2016; 124(1):199-206. PubMed

- Pierre EJ, McNeer RR, Shamir MY. Early management of the traumatized airway. Anesthesiology clinics. 2007; 25(1): 1-11. PubMed

- Mills TJ, DeBlieux, P. Emergency airway management in the adult with direct airway trauma. In: Post R. M. Walls, M. Ganetsky, eds. UpToDate 2022. Accessed June 2022.

- Newton, K. Penetrating neck injuries: Initial evaluation and management. In: Post M. E. Moreira, R. G. Bachur, M. Ganetsky, eds. UpToDate 2022. Accessed June 2022.

- Johnson AM, Hill JL, Zagorksi DJ, et al. Airway management in a patient with tracheal disruption due to penetrating neck trauma with hollow point ammunition: A case report. AA Pract. 2018; 10(9): 242-5. PubMed

Copyright Information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.