Copy link

Marfan Syndrome

Last updated: 08/12/2025

Key Points

- Marfan syndrome is a systemic connective tissue disorder caused by mutations in the FBN1 gene, with widespread cardiovascular, musculoskeletal, and ocular effects.

- The anesthetic management of patients with Marfan syndrome requires a comprehensive, multidisciplinary approach grounded in a strong understanding of the syndrome’s systemic manifestations, particularly its cardiovascular complications.

- Preoperative assessment should focus on aortic root dilation, valvular disease, and airway concerns.

- Intraoperative goals include maintaining hemodynamic stability, avoiding aortic stress, and cautious airway and anesthetic management.

- Postoperative monitoring is essential for cardiovascular and pulmonary complications.

Introduction

- Marfan syndrome is an autosomal dominant disorder caused by mutations in the FBN1 gene, which encodes fibrillin-1, a matrix glycoprotein essential for maintaining connective tissue integrity.1-3

- Fibrillin-1 is a key regulator of transforming growth factor-β, which stimulates inflammation, fibrosis, and metalloproteinases, leading to the weakening of elastic tissue.1 This weakening ultimately affects the cardiovascular, musculoskeletal, and ocular systems.

- Prevalence is approximately 1 in 5,000 individuals.4 However, diagnosis may be challenging due to phenotypic variability and overlap with other connective tissue disorders.

Clinical Presentation

- Clinical manifestations include:

- Cardiovascular: Aortic root dilation, aortic aneurysm/dissection, mitral valve prolapse (MVP), and aortic regurgitation

- Musculoskeletal: Tall stature, scoliosis, joint hypermobility, pectus deformities

- Ocular: Lens subluxation (ectopia lentis), myopia, retinal detachment

- The major cause of morbidity and mortality is aortic dissection, particularly in those with root diameters greater than 5.0 cm or rapid growth (more than 0.5 cm/year).5

Diagnosis

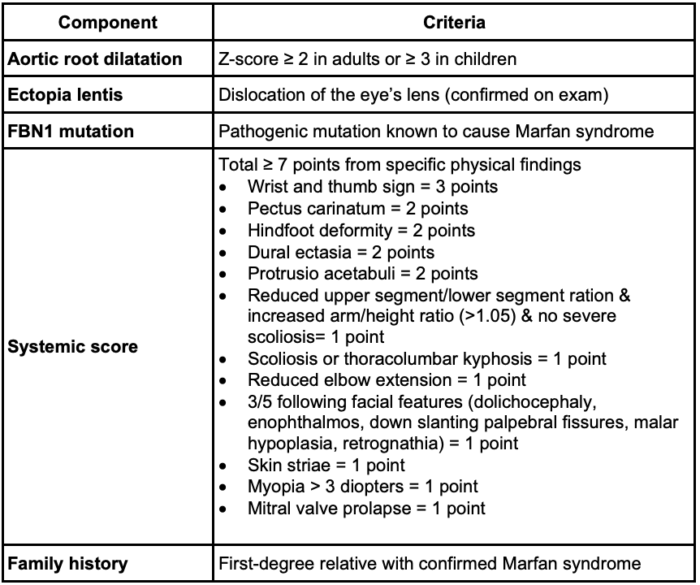

- Since 1996, clinical diagnosis has been based on the Ghent criteria with an updated focus in 2010 on aortic root dilation, ectopia lentis, and FBN1 mutation testing.1

- To be diagnosed in the absence of a family history of the syndrome, a patient must have an aortic root Z score of 2 or greater, along with one of the following: ectopia lentis, a FBN1 mutation, or a systemic score of 7 or greater.

- Having ectopia lentis and an FBN1 mutation with any aortic pathology also qualifies one for the diagnosis without a family history.

- If there is a family history of Marfan syndrome, only one of the following must be present to confirm the diagnosis: ectopia lentis, systemic score greater than 7 or aortic root Z score greater than 2.

- Approximately 1/4th to 1/3rd of cases present with no family history of the disease.1

- Due to the aortic pathology, there was high mortality due to aortic dissection prior to surgical advancements and increased awareness, as well as formal diagnostic criteria.

- The median life expectancy increased from 45 years in 1972 to 72 years in 1995, likely attributable to the Bentall procedure.1

Table 1. GHENT criteria for the clinical diagnosis of Marfan syndrome1

- Advanced imaging techniques, such as computed tomography, magnetic resonance imaging, and transthoracic echocardiography, have played a significant role in the diagnosis of acute sequelae of this syndrome, specifically aortic aneurysm rupture and aortic dissection. This allows for timely treatment to be coordinated after the identification of the acute issue, which has overall improved survival.

Cardiovascular Findings

- The cardiac pathology is one of the cardinal features of this syndrome, likely due to its impact on the morbidity and mortality of patients.

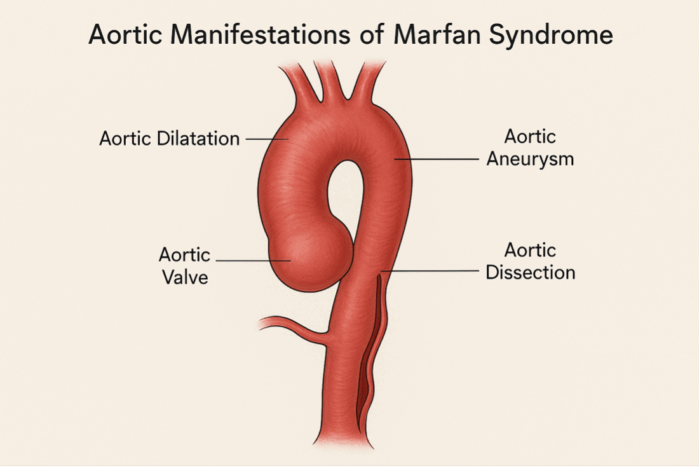

- Cardiac findings include proximal ascending aortic dilation, proximal main pulmonary artery dilation, tricuspid/mitral thickening/prolapse, mitral annular calcification, or rarely, dilated cardiomyopathy1 (Figure 1).

- Aortic regurgitation due to annular enlargement, MVP with or without mitral regurgitation, is also possible.1 Approximately 66% of patients have additional cardiac manifestations other than aortic pathology.1

Figure 1. Aortic pathology of Marfan syndrome

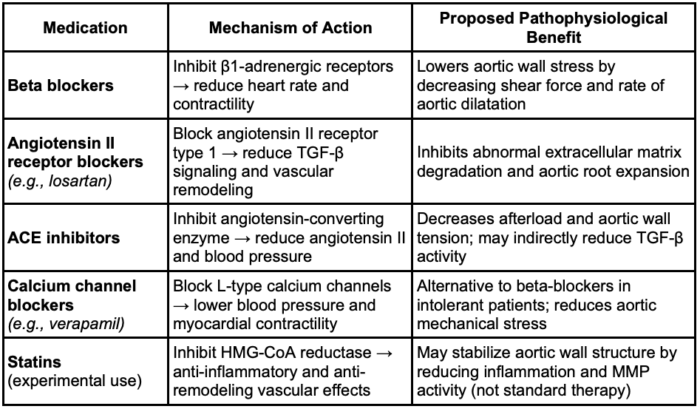

Medical Management1,5,6

- Medical management of Marfan syndrome aims to prevent aortic dissection by slowing the progression of aortic root dilation.

- Beta-blockers, especially atenolol, are first-line therapy due to their capacity to reduce heart rate and aortic wall stress.

- Angiotensin II receptor blockers (ARBs), such as losartan, are recommended as second-line agents or in combination with beta-blockers, targeting dysregulated TGF-β signaling associated with weakening of the aortic wall.

- The COMPARE trial and another randomized controlled trial both support ARBs as a reasonable alternative to beta-blockers, showing comparable effects on aortic root growth in children and young adults.

- Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors and calcium channel blockers may be used in patients who are intolerant to standard therapies, although with less robust evidence.

- Combination therapy is increasingly favored when progressive dilation occurs despite monotherapy.

- The 2022 ACC/AHA Guidelines recommend surgical repair when the aortic root reaches 5.0 cm, or earlier in patients with rapid growth or a family history of dissection.6

Table 2. Medical management of Marfan Syndrome1,5,6 Abbreviation: TGF-β, transforming growth factor-beta

Surgical Management

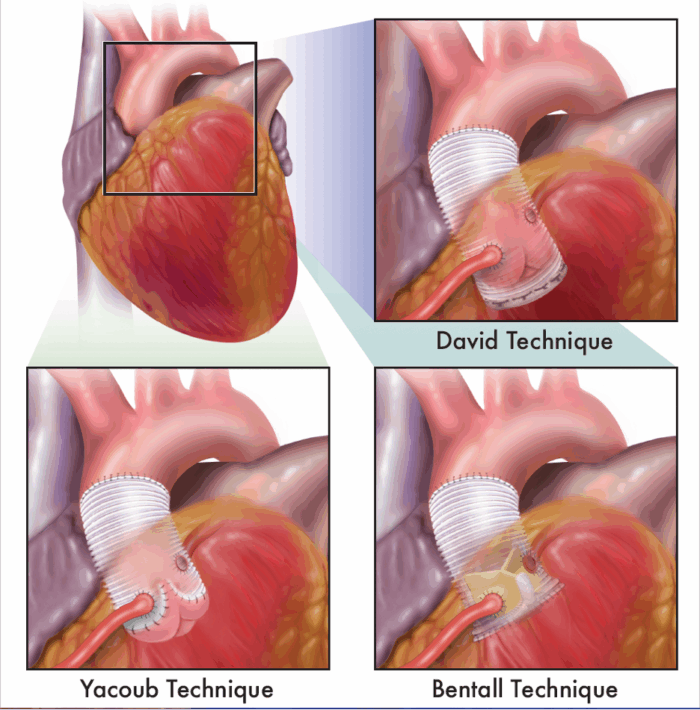

- The Bentall, Yacoub, and David procedures are surgical techniques used to manage aortic root aneurysms, often associated with connective tissue disorders like Marfan syndrome1 (Figure 2).

- The Bentall procedure involves replacing the aortic valve, aortic root, and ascending aorta with a composite graft, along with reimplantation of the coronary arteries, making it ideal for patients with significant valve pathology.1

- The Yacoub procedure is a valve-sparing technique where the aortic root is replaced while preserving the patient’s native valve within a tailored Dacron graft, maintaining more natural valve motion.1

- The David procedure, another valve-sparing approach, involves reimplanting the aortic valve into a Dacron graft, providing more stable annular support compared to the Yacoub technique.1 These procedures offer tailored options depending on valve integrity, patient anatomy, and long-term durability needs.

Figure 2. Surgical techniques for managing aortic root aneurysms. Figure drawn by Sarah St.Claire, RN, University of California Davis.1

Anesthetic Management1

- The anesthetic management of patients with Marfan’s syndrome undergoing aortic aneurysm repair depends on the urgency of the surgery. In symptomatic patients with a leaking or ruptured aneurysm, only a limited preoperative assessment is possible. For elective procedures, a comprehensive preoperative evaluation and multidisciplinary team planning is warranted.1

- Proactive, team-based planning and customized anesthetic approaches lowers the risk of complications and death during surgery in patients with Marfan syndrome.

- Anesthetic considerations include avoiding abrupt changes in blood pressure or heart rate, carefully selecting agents that maintain hemodynamic stability, and accounting for associated features like pectus deformities or cervical spine instability.

- During induction and monitoring, smooth, controlled induction is crucial; intra-arterial blood pressure monitoring, central venous access, and transesophageal echocardiography are strongly recommended for real-time assessment of cardiac function and aortic dimensions.

- For patients undergoing cardiac surgery, extracorporeal circulation strategies should aim to reduce shear stress, often incorporating moderate hypothermia, meticulous myocardial protection, and antegrade cerebral perfusion in extensive aortic repairs.

- In special populations, such as pregnant women with Marfan syndrome, the risk of aortic dissection is significantly increased, necessitating close multidisciplinary management and early delivery planning if the aortic root exceeds 4.5 cm. Women with Marfan syndrome with an aortic root diameter of up to 4.5 cm and no previous cardiac complications seem to tolerate pregnancy well.1 Pregnancy should be discouraged in women with previous aortic dissection because of the high risk for aortic complications.1

- Pediatric patients also require tailored care, as progressive aortic root enlargement can occur early and influence anesthetic and surgical decisions.

Preoperative Considerations

- Cardiovascular evaluation

- Review recent echocardiograms or cardiac imaging.

- Assess for history of aortic root surgery, valve repair/replacement.

- Continue β-blockers or ARBs to reduce wall stress.5

- Airway and pulmonary evaluation

- Be prepared for a difficult airway due to a high-arched palate, retrognathia, or temporomandibular joint laxity.7

- Assess for restrictive lung disease from scoliosis or pectus excavatum.8

- Medication review

- Continue β-blockers and ARBs perioperatively.

- Hold anticoagulants according to standard guidelines for regional techniques.

- Multidisciplinary planning

- Involve cardiology and cardiothoracic surgery for perioperative risk assessment.

Intraoperative Management

- Monitoring

- Standard American Society of Anesthesiologist monitors

- Invasive monitoring (arterial line, central venous line) in high-risk cases

- Hemodynamic goals

- Systolic blood pressure less than 120 mmHg and HR less than 60 bpm should be maintained to prevent dissection.7

- Rapid swings in preload/afterload should be avoided.

- Anesthetic technique

- General anesthesia is preferred in high-risk cases; regional techniques (neuraxial) are relatively contraindicated in patients with anticoagulation or severe scoliosis.9

- Clinicians should use short-acting agents, such as esmolol and nicardipine, for precise blood pressure control.

- Airway considerations

- Clinicians should anticipate and prepare for a difficult airway.

- Video laryngoscopy or awake fiberoptic intubation should be considered in patients with a known difficult airway.

Postoperative Considerations

- Cardiovascular monitoring

- Clinicians should monitor for aortic dissection (chest/back pain, hypotension).

- Antihypertensive medications should be continued early in recovery.

- Pain control

- Multimodal analgesia is preferred to limit sympathetic surges.

- Regional blocks may be used if coagulation is normal and anatomy allows.

- Pulmonary care

- Incentive spirometry and respiratory therapy are used to prevent atelectasis, especially in individuals with restrictive physiology.

- Follow-Up

- Clinicians should e lifelong cardiology follow-up with imaging surveillance.

Conclusion

- In summary, the anesthetic management of patients with Marfan syndrome requires a comprehensive, multidisciplinary approach grounded in a strong understanding of the syndrome’s systemic manifestations, particularly its cardiovascular complications.

- Accurate diagnosis using Ghent criteria, thoughtful medical optimization with beta-blockers or ARBs, and appropriately timed surgical intervention are essential for improving long-term outcomes.

- In the perioperative setting, individualized anesthetic planning focused on hemodynamic control, careful airway management, and vigilant monitoring is critical to minimizing he risk of life-threatening complications such as aortic dissection.

- Special consideration must be given to pediatric and pregnant patients, who represent higher-risk populations. Advances in imaging, surgical techniques, and pharmacotherapy have significantly improved prognosis and life expectancy for these patients.

- Continued collaboration between anesthesiologists, cardiologists, and surgeons remains vital in ensuring safe, effective care for individuals with Marfan syndrome across all stages of their treatment journey.

References

- Castellano JM, et al. Marfan Syndrome: Clinical, Surgical, and Anesthetic Considerations. 2014;18(30):260-271. PubMed

- Dietz HC. Marfan syndrome. Nat Rev Genet. 2005;6(12):940-951. PubMed

- von Kodolitsch Y, et al. Perspectives on the revised Ghent criteria for the diagnosis of Marfan syndrome. Appl Clin Genet. 2015;8(1):137-155. PubMed

- Salik I, Rawla P. Marfan syndrome. In: StatPearls (Internet). Treasure Island, FL. StatPearls Publishing; 2025. Accessed April 2025. PubMed

- Milewicz DM, Ramirez F. Therapeutics targeting drivers of aortic disease in Marfan syndrome. Annu Rev Med. 2017;68(8):51-67. PubMed

- Isselbacher EM, Preventza O, Hamilton Black 3rd, J. 2022 ACC/AHA Guideline for the diagnosis and management of aortic disease. Circulation. 2022;146(1):e334–e482. PubMed

- Wright MJ. Marfan syndrome: Cardiovascular manifestations and management. In: Post T, ed. UpToDate; 2025. Accessed April 2025. Link

- Barash PG, Cullen BF, Stoelting RK, et al. Cardiac Anesthesia. In: Barash PG, Cullen BF, editors. Clinical Anesthesia, 8th ed. Philadelphia; Wolters Kluwer; 2017:1150-1175.

- Hines RL, Marschall KE. Vascular Disease. In: Hines RL, Marschall KE, editors. Stoelting’s Anesthesia and Co-Existing Disease. 8th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2021:325–345

Copyright Information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.