Copy link

Liver Pathology in Pregnancy

Last updated: 10/24/2025

Key Points

- Pregnancy and liver dysfunction share overlapping physiologic features (e.g., elevated estrogen, hyperdynamic circulation, mild cholestasis), which can complicate diagnosis.

- Liver disease affects up to 3% of pregnancies. It includes both diseases incidental to pregnancy (e.g., viral hepatitis, autoimmune hepatitis, Budd-Chiari) and pregnancy-specific disorders (e.g., intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy, acute fatty liver of pregnancy, hemolysis-elevated liver enzymes-low platelets [HELLP] syndrome).

- Disease severity, not etiology, determines prognosis; acute fatty liver and HELLP syndrome carry the highest maternal and fetal morbidity.

- Coagulopathy, thrombocytopenia, and encephalopathy may limit neuraxial options and increase risk with general anesthesia.

Introduction

- Liver disease complicates approximately 3% of all pregnancies, ranging from mild laboratory abnormalities to fulminant hepatic failure.1,2

- Conditions are classified as pregnancy-specific (e.g., intrahepatic cholestasis, acute fatty liver of pregnancy, HELLP) or incidental to pregnancy (e.g., viral hepatitis, autoimmune hepatitis, Budd-Chiari).1,2

- Pregnancy-specific disorders typically present in the late second or third trimester and may rapidly progress to maternal or fetal compromise.2

- The physiologic overlap between normal pregnancy and liver dysfunction (e.g., hyperdynamic circulation, hemodilution, reduced albumin, elevated alkaline phosphatase) can make diagnosis challenging.2

- Maternal morbidity and mortality are primarily driven by hepatic failure, coagulopathy, and obstetric complications such as preeclampsia and hemorrhage.2

- Fetal risks include preterm delivery, growth restriction, and stillbirth, depending on maternal disease severity.

- Obstetric indications determine the mode of delivery, but timely delivery is often lifesaving in acute maternal hepatic decompensation.2

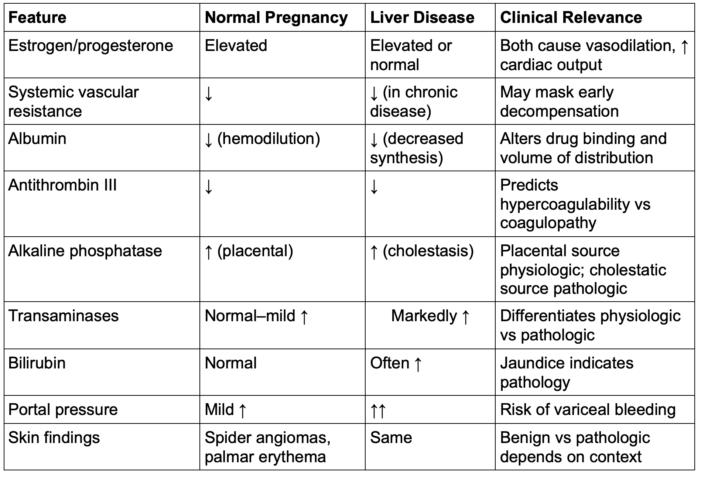

Hepatic Physiology1-4

- Normal pregnancy produces hormonal, hemodynamic, and metabolic adaptations that may mimic liver dysfunction.

- Estrogen and progesterone promote systemic vasodilation and increased cardiac output, resulting in a hyperdynamic circulation similar to that observed in chronic liver disease.

- Alkaline phosphatase increases two to fourfold from placental production; mild transaminase elevations can occur but are typically within the normal range for nonpregnant adults.

- Albumin concentration decreases due to hemodilution, which reduces oncotic pressure and alters drug-protein binding.

- Antithrombin III levels decline in normal pregnancy, producing a hypercoagulable state; in liver disease, this decrease may reflect impaired synthesis and contribute to unpredictable coagulation status.

- Portal pressures increase modestly in late pregnancy, and esophageal varices may develop even in women without preexisting liver disease.

- Spider hemangiomas and palmar erythema can appear physiologically in pregnancy but are also classic signs of chronic hepatic dysfunction.

- The physiologic overlap between pregnancy and hepatic pathology can delay recognition of liver disease and complicate anesthetic and obstetric management.

Table 1. Comparison of pregnancy vs. liver disease features

Liver Diseases in Pregnancy

Diseases Incidental to Pregnancy

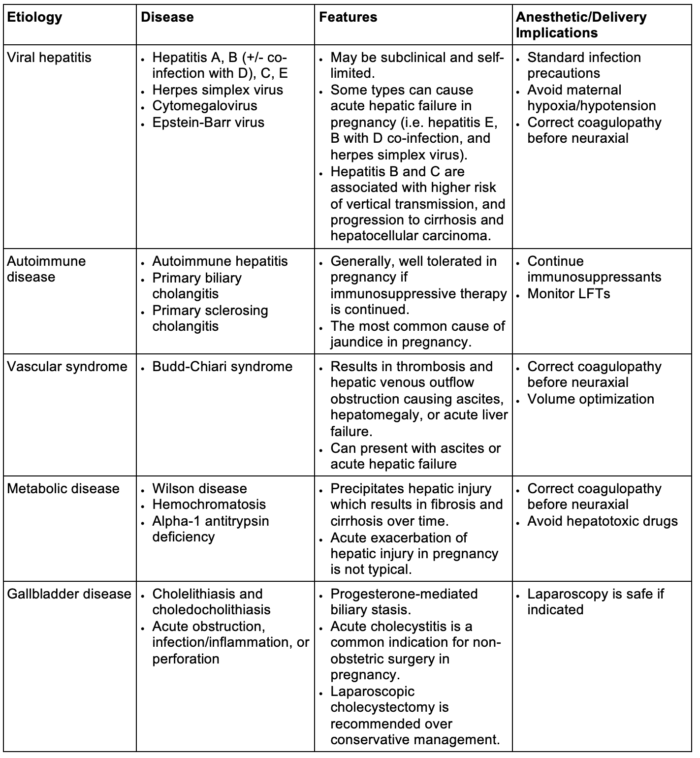

- Incidental liver disease is that which may occur in any population but coincides with pregnancy.

- These include viral, autoimmune, vascular, metabolic, and gallbladder disease (Table 2).

- Disease manifestations and outcomes depend on the severity of hepatic dysfunction rather than etiology.

- Obstetric implications for incidental disease vary by disease type and can include fetal growth restriction, preterm delivery, neonatal respiratory distress syndrome, hypertensive complications, hemorrhage, and caesarean delivery.3

- Cirrhosis is an end-stage complication of chronic liver disease incidental to pregnancy. Although it is associated with anovulation, amenorrhea and infertility, the number of women becoming pregnant with cirrhosis is increasing.2

- Multidisciplinary care (obstetrics, hepatology, anesthesia) is essential, especially in women with cirrhosis or portal hypertension, who are at risk for variceal bleeding (up to 25%).4

Table 2. Diseases incidental to pregnancy.

Abbreviation: LFTs, liver function tests

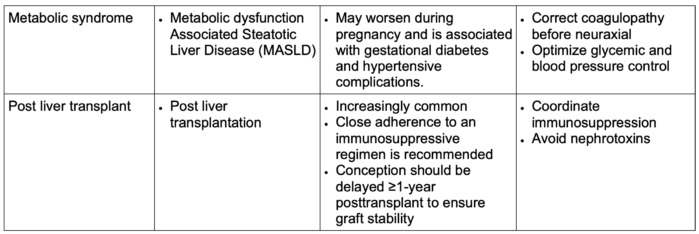

Diseases Specific to Pregnancy

Table 3. Diseases specific to pregnancy.2,3

Abbreviations: LFTs, liver function tests; DIC, disseminated intravascular coagulation; IUGR, intrauterine growth restriction; ARDS, acute respiratory distress syndrome; ICU, intensive care unit

Anesthetic Considerations

General Considerations1,3,5

- Management depends on the presence and severity of hepatic impairment, rather than solely on the disease type.

- Patients with liver disease without hepatic impairment can often be managed similarly to healthy parturients.

- Parturients with significant liver dysfunction should deliver at a Level II or III maternal care center with critical care, hepatology support, maternal-fetal medicine, and obstetric anesthesiology support.

- Goals should be to maintain intravascular volume and organ perfusion, correct coagulopathy, prevent hypoglycemia, and minimize hepatotoxic drug exposure.

- Multidisciplinary coordination (obstetric, anesthesia, hepatology, critical care, neonatology) is essential for optimal timing of delivery and anesthetic planning.

- Drug pharmacokinetics are altered: ↓ protein binding, ↑ volume of distribution, ↓ metabolism, and impaired excretion → require dose titration and cautious use of sedatives and opioids.

- These changes place patients at high risk for local anesthetic toxicity, specifically bupivacaine toxicity, as it is highly protein-bound.1

- Patients with hemodynamic instability or encephalopathy may be particularly sensitive to anesthetics, opioids, and benzodiazepines, and judicious use is recommended.3

- Avoid hepatotoxins: acetaminophen ≤ 2 g/day in decompensated disease; avoid nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs due to renal and bleeding risk and fetal closure of ductus arteriosus (depending on gestational age)

- Monitor for hypoglycemia and hemodynamic instability peridelivery; arterial line or central access may be appropriate for severe disease.

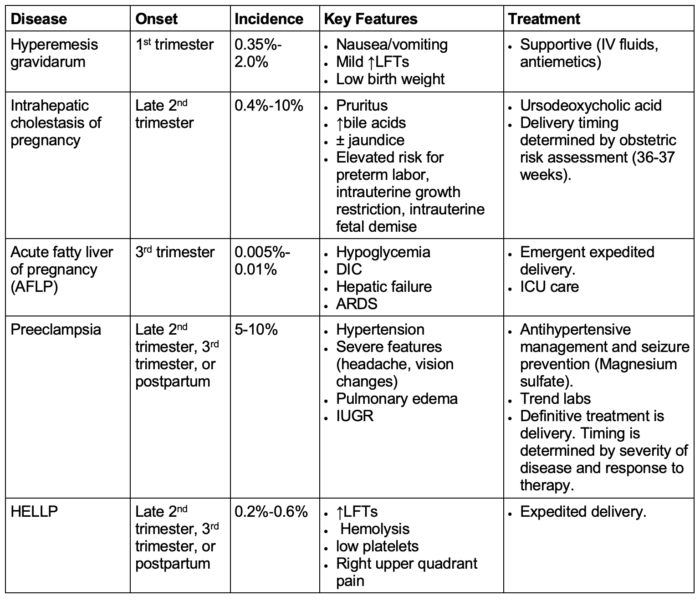

Neuraxial Anesthesia1,5

- Preferred for obstetric anesthesia and analgesia when coagulation parameters permit.

- Neuraxial techniques are preferred in obstetric patients for analgesia and surgical anesthesia.1

- Contraindications: hypovolemia, thrombocytopenia (platelets < 70,000 × 106/L), and coagulopathy (INR > 1.5)1

- Assess platelet trend and illness trajectory before block placement; re-check coagulation in evolving conditions (e.g., HELLP, AFLP).

- The potential for impaired clearance of local anesthetics and opioids should be considered.5

- Epidural test dose should be incremental; metabolism and clearance of local anesthetics may be reduced → ↑ risk of toxicity (especially bupivacaine).

- Systemic analgesia with inhaled nitrous oxide or opioid patient-controlled analgesia may be considered for labor in cases where neuraxial is contraindicated. Both alternatives require patient cooperation.

- Close monitoring for respiratory depression and sedation is needed for opioid-based techniques.

- Remifentanil is an ideal agent as it does not rely on hepatic metabolism.3

General Anesthesia3,5

- Indicated for obstetric emergencies, decompensated hepatic failure, or when neuraxial is contraindicated

- Aspiration risk is elevated → employ rapid sequence induction and video laryngoscopy.

- Use agents with minimal hepatic metabolism (propofol, sevoflurane, desflurane, isoflurane, nitrous oxide)

- Anticipate increased sensitivity to induction agents and opioids; titrate doses to effect.

- Maintain stable perfusion pressure and avoid hypotension to preserve hepatic and uteroplacental blood flow.

- Uterotonics (oxytocin, carboprost, methylergometrine) may be used at standard doses despite hepatic metabolism.

- Intraoperative bleeding is typically due to portal hypertension and mucosal friability rather than isolated coagulopathy.

- General anesthesia does not worsen maternal mortality, provided hemodynamics are well maintained.

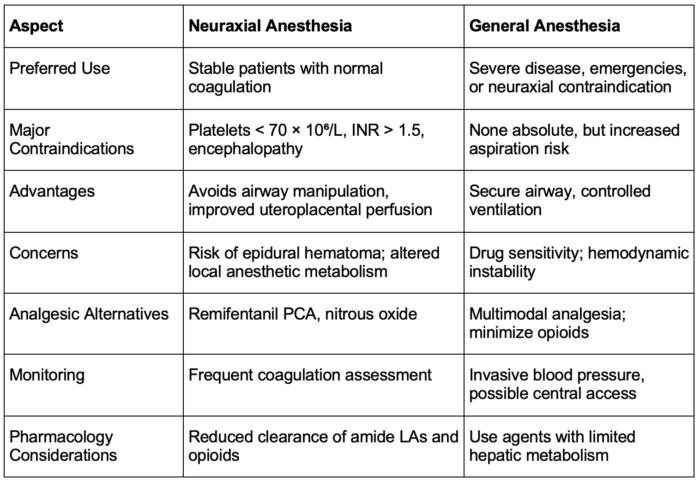

Table 4. Neuraxial vs general anesthesia in liver disease.1,3,5

Abbreviations: INR = international normalized ratio, LA = local anesthetics

References

- Hansen JD, Perri RE, Riess ML. Liver and biliary disease of pregnancy and anesthetic implications: A review. Anesth Analg. 2021;133(1):80-92. PubMed

- Sarkar M, Brady CW, Fleckenstein J, et al. Reproductive health and liver disease: Practice guidance by the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases. Hepatology. 2021;73(1):318-365. PubMed

- Wax DB, Beilin Y. Liver disease. In: Chestnut’s Obstetric Anesthesia: Principles and Practice. In: Chestnut DH, Wong CA, Tsen LC, Ngan Kee WD, Beilin Y, Mhyre JM, Bateman BT, Nathan N. Chestnut's Obstetric Anesthesia: Principles and Practice. 6th ed. Philadelphia; Elsevier; 2020:1112-21.

- Joshi D, James A, Quaglia A, et al. Liver disease in pregnancy. Lancet. 2010;375(9714):594-605. PubMed

- Griffiths S, Nicholson C. Anaesthetic implications for liver disease in pregnancy. BJA Education. 2015;16(1):21-25. Link

Copyright Information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.