Copy link

Intracranial Lesions in Pregnancy

Last updated: 10/15/2025

Key Points

- Pregnancy-related hormonal and hemodynamic changes can exacerbate the presentation of intracranial lesions.

- Risk stratification based on lesion characteristics, imaging, and symptoms is critical when evaluating the safety of neuraxial anesthesia in a parturient with an intracranial lesion.

Introduction

- Intracranial lesions are rarely diagnosed during pregnancy. The incidence is approximately 5.2 out of 100,000 of all women, and this appears to be about the same rate for pregnant women.1

- Symptoms include:1

- Headache (initial symptom in 36-90% of all tumors)

- Altered mental status

- Vomiting

- Seizures (30-50% of intracranial tumors during pregnancy initially present with seizures)

- The presence of these symptoms may indicate that the patient has increased intracranial pressure (ICP).

Neurophysiological Changes During Pregnancy, Labor, and Delivery

- During pregnancy, cerebrovascular blood flow and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) pressure remain unaltered.2

- During labor, there is an increase in CSF pressure during painful uterine contractions, which is mitigated with effective labor analgesia.2

- During delivery, expulsive efforts/Valsalva result in an increase in cerebral blood volume and CSF volume, increasing ICP. Excellent neuraxial analgesia and assisted second stage of labor (vacuum or forceps) may minimize this additional rise in ICP.2

Intracranial Lesions1,3

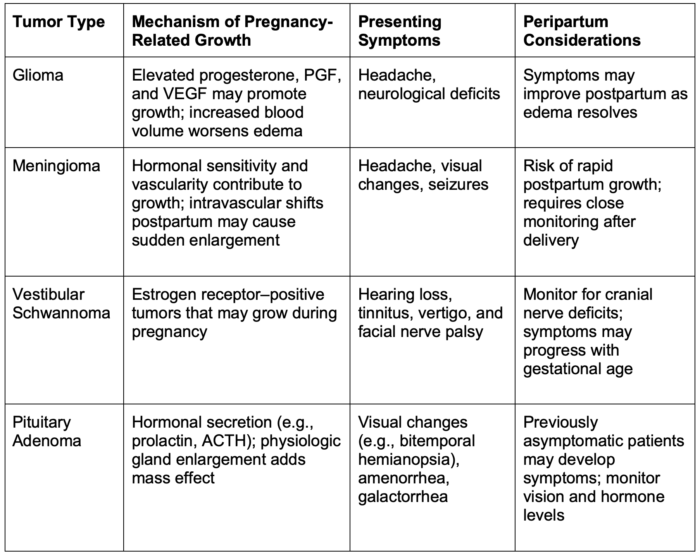

- The four most common intracranial lesions are gliomas, meningiomas, vestibular schwannomas, and pituitary tumors.

Table 1. Common intracranial lesions during pregnancy.

Abbreviations: ACTH, adrenocorticotropic; PGF, prostaglandins; VEGF, vascular endothelial growth factor

Management

- Treatment should be tailored as if the patient were not pregnant and then modified based on fetal risks.1

Medical Management

- Steroids can help alleviate edema and delay surgery until after delivery. They are generally safe in pregnancy but may increase the risk of neonatal adrenal suppression.

- Antiepileptics are teratogenic, but the prevention of seizures during pregnancy outweighs these risks.1,4 They should only be used in patients who have a history of seizures.

- Treatment of functional pituitary adenomas requires a unique set of medications.

- Bromocriptine, cabergoline (prolactinoma)

- Somatostatin analogs (growth hormone-secreting adenoma)

- Metyrapone and ketoconazole (adrenocorticotropic-secreting adenoma)

Surgical Management

- Surgery is reserved for aggressive high-grade malignancies, masses refractory to medical treatment, or life-threatening conditions (i.e., impending herniation or refractory seizures)

- About 9% of operations in general have been associated with preterm labor.5

- If surgery is deemed necessary during pregnancy, a multidisciplinary team – including maternal-fetal medicine, neurology/neurosurgery, and obstetric anesthesiology – should coordinate the patient’s care. Intraoperative fetal heart rate monitoring may be required depending on gestational age. All preparations should be made for an emergent cesarean delivery if necessary.

Arnold Chiari Malformations

- Chiari type I malformation is associated with the herniation of cerebellar tonsils through the foramen magnum by at least 5 mm. These are often asymptomatic or diagnosed in late childhood or adulthood.

- No cases of significant brainstem herniation during pregnancy have been reported in the literature.6

- However, these malformations can occasionally be associated with a closed dysraphism such as a tethered cord or a low-lying spinal cord. Given that case reports have described neurologic injury after neuraxial administration, spine imaging should be performed before proceeding.7

- Chiari type II malformation is less common and involves herniation of the cerebellar vermis, tonsils, brainstem, and fourth ventricle. They are often associated with severe neurologic deficits and are usually corrected before childbearing age.

- Chiari II malformations are often associated with open spinal dysraphism. However, a single-level isolated laminar arch defect rarely poses an issue for neuraxial as the lesion typically occurs at L5-S1.7

- The epidural space may be discontinuous across the defect; however, this rarely interferes with the performance of an epidural or spinal anesthetic.7

- Multiple reports have been described of patients with and without corrected Chiari malformations undergoing neuraxial without herniation.8

- These patients should see an obstetric anesthesiologist in consultation prior to delivery.

Neurofibromatosis

- Neurofibromatosis is caused by excessive proliferation of neural crest elements such as Schwann cells, melanocytes, and fibroblasts.3

- Imaging should be considered before neuraxial placement, as these patients may have intracranial tumors or paraspinal neurofibromas.3

- Severe kyphoscoliosis from paraspinal tumors may make neuraxial placement technically difficult if it is not contraindicated.3

Neuraxial vs General Anesthesia

- When assessing the risk of neuraxial anesthesia in these patients, the most relevant characteristics of an intracranial lesion are its location/size, the rate of expansion of associated brain tissue, imaging evidence of preexisting fluid/tissue shifts, or obstruction to CSF pathways.

- Parturients with space-occupying lesions without mass effect, hydrocephalus, or clinical/imaging findings suggestive of increased ICP are likely to have minimal to no increased risk of herniation from a dural puncture.

- If the lesion obstructs the flow of CSF, parturients are more likely to have brain herniation after a dural puncture.

- In idiopathic intracranial hypertension (pseudotumor cerebri), there is no increased risk of herniation because there is a uniform, global increase in ICP.

- Epidural vs spinal

- Due to the risk of dural puncture, epidural placement carries an increased risk in patients with space-occupying lesions. A small-gauge spinal needle may be preferable. The risks and benefits should be thoroughly assessed and discussed with the patient before proceeding.8

- When caring for a pregnant patient with an intracranial lesion, antepartum anesthesia consultation, along with multidisciplinary discussion with obstetrics, neurology, neurosurgery, and neonatology, is crucial.

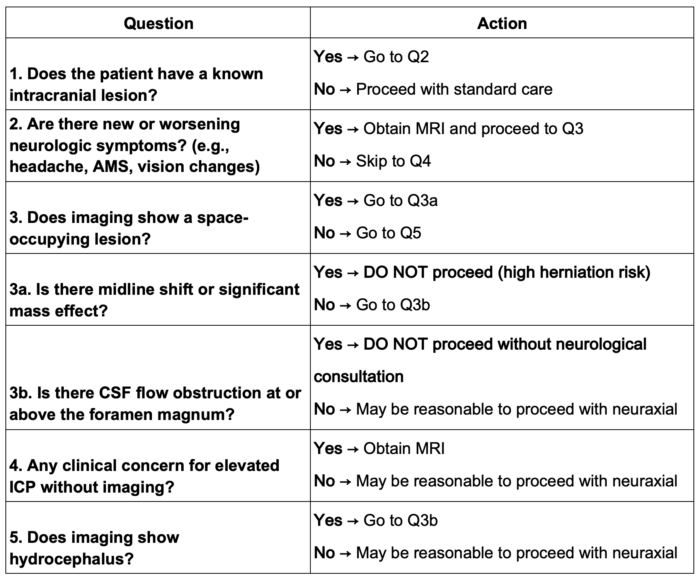

This decision-making table was adapted from Leffert et al.8 It can be used to risk-stratify patients before neuraxial anesthesia.

Table 2. Decision-making table for a pregnant patient with an intracranial lesion. It decision can be used to risk-stratify patients before neuraxial anesthesia. Adapted from Leffert et al.8

Abbreviations: AMS, altered mental status; CSF, cerebrospinal fluid; ICP, intracranial pressure

General Anesthesia

- General anesthesia also carries risks in these patients

- Neurologic assessment is more difficult due to loss of verbal and motor responses

- Increased risk of causing increased ICP with intubation and extubation

- Caution is advised in scenarios where rapid sequence intubation (RSI) cannot be avoided. RSI can make it more difficult to blunt the hemodynamic responses during laryngoscopy and intubation

- When caring for a pregnant patient undergoing neurosurgery for an intracranial lesion, the following should be considered:9

- Rapid sequence induction only if the patient is at increased risk for aspiration. Not all pregnant patients are at increased risk of aspiration (e.g., nonlaboring, nondiabetic, noninfected).

- Left lateral tilting to avoid aortocaval compression

- Perioperative fetal heart rate monitoring, and intraoperative monitoring can be considered on an individual basis

- Minimize hypertension during induction with agents like propofol, remifentanil, and fentanyl.

- Maintain PaCO2 between 25–30 mmHg

- Mannitol may be used cautiously, as it accumulates in the fetus and can cause adverse effects on fetal osmolality.9

- When caring for a pregnant patient with an intracranial lesion, antepartum anesthesia consultation along with multidisciplinary discussion with obstetrics, neurology, neurosurgery, and neonatology are crucial.

References

- Tang OY, Liu JK. Management of brain tumors in pregnancy. In: Gupta G, Rosen T, Al-Mufti F, et al., eds. Neurological Disorders in Pregnancy: A Comprehensive Clinical Guide. Springer International Publishing; 2023:489-502.

- Clark KJ, Chau A. Neuraxial techniques in obstetric patients with intracranial lesions. Curr Obstet Gynecol Rep. 2023;12(1):1-7. Link

- Lim G, Bader A. Neurologic and neuromuscular disease. In: Chestnut’s Obstetric Anesthesia: Principles and Practice. 6th ed. Elsevier; 2019:1053-1078.

- Tomson T, Battino D, Perucca E. Teratogenicity of antiepileptic drugs. Curr Opin Neurol. 2019;32(2):246-252. PubMed

- Delaney AG. Anesthesia in the pregnant woman. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 1983;26(4):795-800. PubMed

- Simpson A, Ferguson C. Anaesthetic management of obstetric patients with Chiari type I malformation: a retrospective case series and literature review. Int J Obstet Anesth. 2024; 60:104232. PubMed

- Preston R. Musculoskeletal Disorders. In: Chestnut’s Obstetric Anesthesia: Principles and Practice. 6th ed. Elsevier; 2019:1139-1159.

- Leffert LR, Schwamm LH. Neuraxial anesthesia in parturients with intracranial pathology: A comprehensive review and reassessment of risk. Anesthesiology. 2013;119(3):703. PubMed

- Wang LP, Paech MJ. Neuroanesthesia for the Pregnant Woman. Anesth Analg. 2008;107(1):193. Link

Copyright Information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.