Copy link

Infections from Needle Stick Injuries

Last updated: 09/08/2025

Key Points

- The primary occupational risk for healthcare personnel is a percutaneous sharps injury, most commonly from syringes (24%) and suture needles (25%), which can transmit human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), hepatitis B virus (HBV), and hepatitis C virus (HCV). Risk is higher among medical trainees with fatigue, and sharps injuries occur more frequently in teaching hospitals.

- HIV seroconversion risk is low (~0.36%) but increases with deep injuries or contaminated devices. HBV is highly infectious, with seroconversion rates ranging from 23% to 62%, depending on the source, and 2–5% of those infected progress to chronic infection. HCV has a seroconversion risk of ~1.8%, with over 75% developing chronic infection, some progressing to cirrhosis or liver cancer.

- Standard precautions (gloves, proper sharps disposal) and safety-engineered devices reduce risk. After exposure, immediate wound cleaning, baseline physical exam, and blood tests for HIV, HBV, and HCV (plus pregnancy testing for women) are recommended.

Introduction1,2

- The primary occupational risk for acquiring bloodborne pathogens is a percutaneous sharps injury with a contaminated object, which can transmit HIV, HBV, and HCV. The most common devices involved in percutaneous injuries are disposable syringes (24%) and suture needles (25%), typically used for suturing, administering injections, or drawing venous blood.

- This risk is particularly elevated among medical trainees, who have a threefold increased risk when experiencing fatigue from long work hours and sleep deprivation. Approximately 385,000 sharps-related injuries occur annually among healthcare personnel in hospitals. In 2018, both needlestick/sharp object injuries and blood and body fluid exposures were more frequent in teaching hospitals compared with nonteaching hospitals.

- To mitigate these risks, standard precautions should be applied in the care of all patients. These include the routine use of gloves when handling blood, body fluids, or contaminated materials. Additional protective strategies include double gloving during high-risk procedures, using blunted suture needles, self-sheathing needles, needleless systems, and reinforcing education and training on safe practices.

- Several factors increase the likelihood of blood exposure. These include failure to follow standard precautions, not adhering to safety protocols, performing high-risk procedures (e.g., phlebotomy, dialysis, blood administration), and the use of sharps without safety features. Strengthening adherence to established precautions and improving the design and use of safety-engineered devices are key to reducing occupational exposures.

Etiology1,2,3

- Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV): HIV attacks the immune system and can progress to AIDS, increasing vulnerability to infections and cancer. The risk of seroconversion after a needlestick is 0.36%. Factors increasing risk include deep injuries, devices visibly contaminated with blood, needle placement in a vein or artery, terminal illness in the source patient, and high viral load. Early signs of infection after a needlestick injury typically manifest as an acute retroviral syndrome resembling mononucleosis or influenza. Late signs of HIV infection include persistent generalized lymphadenopathy, opportunistic infections, constitutional symptoms (e.g., weight loss, night sweats), and AIDS-defining illnesses.

- Hepatitis B (HBV): HBV is highly infectious, and the risk depends on the HBsAg and HBeAg status of the source. Seroconversion occurs in 37–62% of cases if both HBsAg and HBeAg are positive, and in 23–37% of cases if only HBsAg is positive. 30–50% of infected individuals experience symptoms like jaundice, fever, and nausea, usually resolving in 4–8 weeks. Chronic infection occurs in 2–5%, with a lifetime 15% risk of cirrhosis or liver cancer.

- Hepatitis C (HCV): Needlestick injuries are the main route of HCV transmission. Seroconversion risk is ~1.8%. Most exposed individuals are asymptomatic or have mild, flu-like symptoms. Over 75% of adults develop chronic infection, with ~20% progressing to end-stage liver disease or cirrhosis, and 1–5% developing hepatocellular carcinoma over 20–30 years.

Management2

- Most needlestick injuries cause no obvious symptoms besides the puncture wound. A baseline physical examination should be performed to help detect any future infections. Blood tests should be obtained from both the source patient (if available) and the exposed healthcare worker to check for HIV, HBV, and HCV. A pregnancy test should be done for women of childbearing age.

- The needlestick site should be thoroughly rinsed with water or saline and properly cleaned. Caustic agents (e.g., bleach) should not be applied to the wound. The use of topical antiseptics and/or expressing fluid by squeezing the wound has not been shown to reduce the risk of transmission.

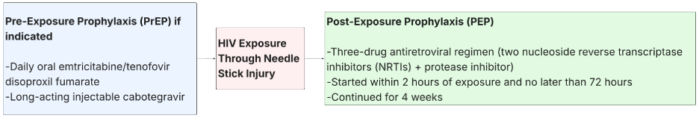

Figure 1. Management of HIV exposure through needle stick injury2,3

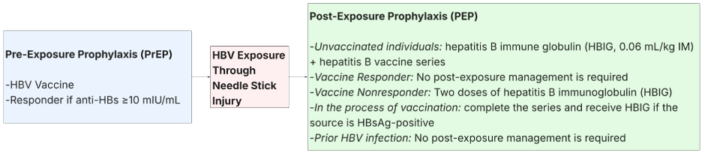

Figure 2. Management of HBV exposure through needle stick injury1, 2

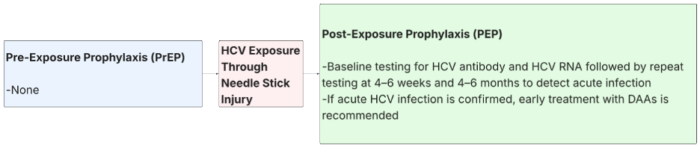

Figure 3. Management of HCV exposure through needle stick injury1,2

References

- Weber D, Prevention of hepatitis B virus and hepatitis C virus infection among health care providers. In: Ghandi RT, Shefner JM, eds. UpToDate; 2025. Accessed September 1, 2025. Link

- King KC, Strony R. Needlestick. In: StatPearls (Internet). Treasure Island, FL. StatPearls Publishing; 2023. Accessed September 1, 2025. Link

- Zachary KC, Management of health care personnel exposed to HIV. In: Gulick RM, eds. UpToDate; 2023. Accessed September 1, 2025. Link

Copyright Information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.