Copy link

Hypertensive Disorders of Pregnancy

Last updated: 01/19/2024

Key Points

- Hypertensive disorders of pregnancy are a leading cause of maternal and perinatal morbidity and mortality.

- The pathophysiology of preeclampsia is hypothesized to be due to abnormal placentation and systemic vascular endothelial dysfunction.

- Maternal complications include cerebral vascular accident, pulmonary edema, placental abruption, renal failure, and HELLP syndrome.

- Neonatal complications include preterm delivery, fetal growth restriction, hypoxic-ischemic neurologic injury, and perinatal death.

- The risk for serious complications persists in the postpartum period.

Introduction

- Hypertension is the most common medical disorder of pregnancy, and its incidence is increasing in the setting of advanced maternal age and obesity.1

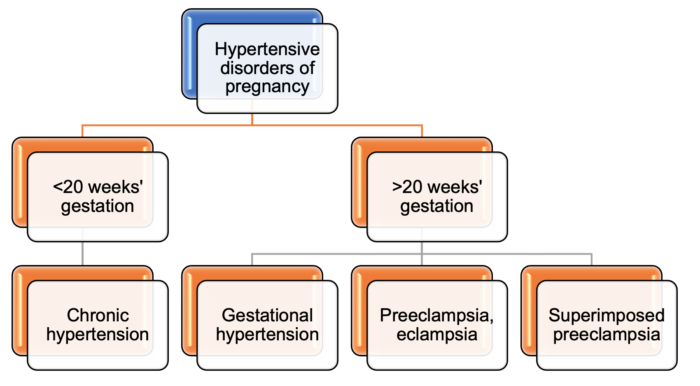

- The range of conditions include chronic hypertension, gestational hypertension, preeclampsia (with or without severe features), preeclampsia superimposed on chronic hypertension, and eclampsia.

- Classification is important due to significant differences in underlying pathophysiology (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Classification of hypertensive disorders of pregnancy

Chronic Hypertension of Pregnancy

- Chronic hypertension of pregnancy is defined as a systolic blood pressure greater than 140 mmHg or diastolic blood pressure greater than 90 mmHg that presents before 20 weeks gestation or does not resolve postdelivery.2

- It develops into preeclampsia in 20-25% of affected patients.

- Chronic hypertension with superimposed preeclampsia has increased morbidity for mother and fetus than preeclampsia alone.2

Gestational Hypertension

- Gestational hypertension is the most common hypertensive disorder of pregnancy, affecting 5% of pregnancies.2

- It is defined as an elevated blood pressure developing after 20 weeks gestation in the absence of proteinuria. Gestational hypertension must resolve by 12 weeks postpartum; otherwise, it is categorized as chronic hypertension.

- Gestational hypertension develops into preeclampsia in 25% of affected patients.2

Preeclampsia

- In the United States, preeclampsia occurs in about 3-4% of pregnancies.2

- It is defined as elevated blood pressure and proteinuria developing after 20 weeks gestation and (usually) before 7 days postpartum.2

- If end-organ dysfunction is present, proteinuria is not necessary for the diagnosis.

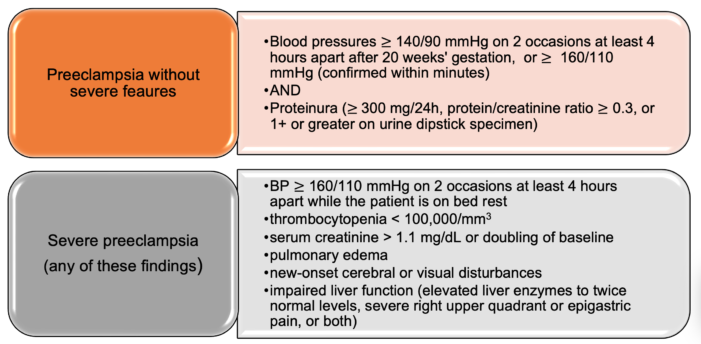

- Preeclampsia is further classified as with or without severe features2 (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Classification of preeclampsia

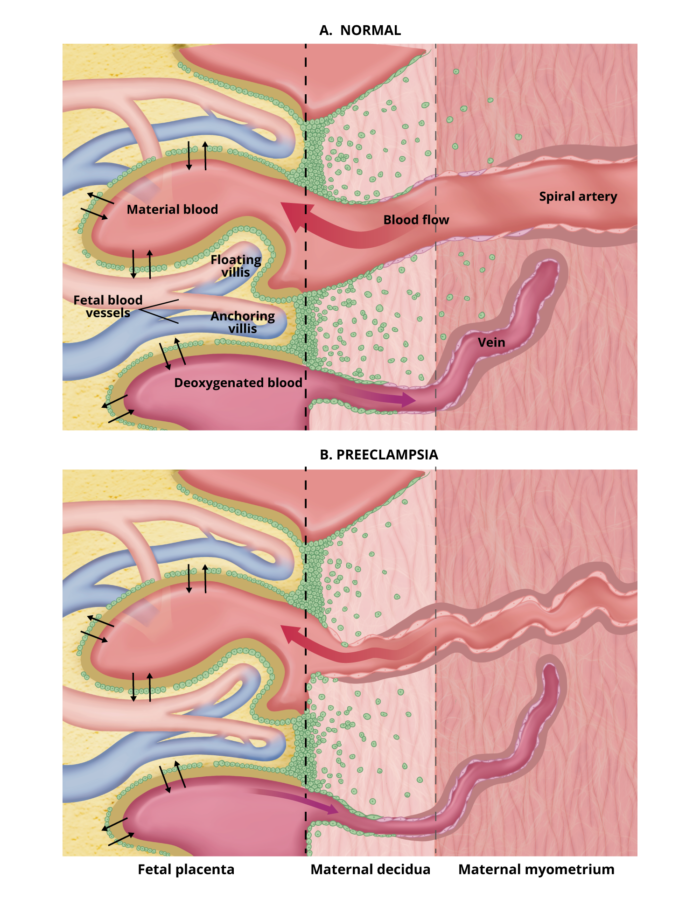

- The pathogenesis of preeclampsia is abnormal placentation due to impaired angiogenesis of spiral arteries (terminal branches of the uterine artery), leading to placental ischemia and release of antiangiogenic factors to maternal circulation, leading to systemic endothelial dysfunction.3

- During normal placental development, fetal cytotrophoblasts invade the maternal spiral arteries, converting them into large caliber capacitance vessels capable of providing adequate placental perfusion to sustain fetal growth (Figure 3A). During the vascular invasion, the fetal cytotrophoblasts differentiate from the epithelial phenotype to the endothelial phenotype. In preeclampsia, the fetal cytotrophoblasts fail to differentiate into the invasive endothelial phenotype. The end result is a shallow invasion of the maternal spiral arteries, which remain small-caliber, high-resistance vessels (Figure 3B). This results in relative placental under perfusion, hypoxia, oxidative stress, and release of antiangiogenic factors into the maternal circulation, causing widespread systemic maternal endothelial dysfunction (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Abnormal placentation in preeclampsia.Redrawn from Karumanchi SA, et al. Preeclampsia: pathogenesis. In: UpToDate. 2023.

- Clinical Manifestations and Complications:2

- Neurologic: headache, visual disturbances; can progress to seizure (eclampsia)

- Airway: exaggerated airway narrowing due to edema

- Cardiovascular: hypertension, cerebrovascular accident, myocardial ischemia, heart failure

- Pulmonary: edema, respiratory failure

- Hematologic: thrombocytopenia, disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC)

- Hepatic: ranges from mild hepatocellular necrosis to HELLP syndrome

- Renal: proteinuria, oliguria, renal failure

- Placental abruption

Eclampsia

- Eclampsia is defined as a seizure in a pregnant or postpartum patient with signs/symptoms of preeclampsia without preceding neurologic disease.2

- Most patients have precluding neurologic symptoms: headache, visual disturbances, altered mental status.2

- The pathophysiology is not well understood but is likely due to hyperperfusion causing cerebral edema.2

- The differential diagnosis for seizure in pregnancy is broad but should be considered eclampsia until proven otherwise.

Management

Expectant Management vs. Delivery

- Gestational hypertension and preeclampsia without severe features: induction of labor after 37 weeks gestation.4

- Preeclampsia with severe features: induction after 34 weeks gestation.2

- Eclampsia: expedited delivery within 24-48 hours once maternal condition is stable.5

Blood Pressure Management

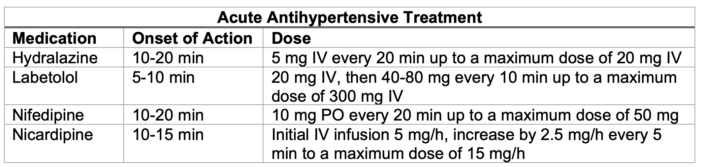

- Antihypertensives should be administered for systolic BP ≥ 160 mmHg or diastolic BP ≥ 90 mmHg with the goal of preventing maternal hypertensive encephalopathy, cerebrovascular hemorrhage, myocardial ischemia, and congestive heart failure2 (Table 1).

- The goal is to treat within one hour to reduce the risk of strokes.1

Table 1. Antihypertensive medications commonly used in pregnancy.

Abbreviations: IV = intravenous, PO = per oral

Platelet Count

- A platelet count should be checked prior to a neuraxial procedure, and it should ideally be greater than 70,000/mm3, though the risk of epidural hematoma is poorly defined in patients with a platelet count lower than 70,000/mm3.2

Seizure Prophylaxis

- Magnesium sulfate should be administered for seizure prophylaxis.

- Magnesium is indicated in patients with preeclampsia with severe features.

- Studies have failed to show improved outcomes in patients without severe features.1

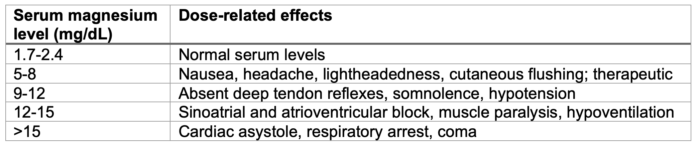

- The therapeutic range for dosing is 5-8 mg/dL2 (Table 2).

- Magnesium should be continued throughout delivery.

- Please see the OA summary on magnesium use in pregnancy. Link

Table 2. Dose-related effects of serum magnesium levels

Active Seizures

- The patient should be turned to the left side, and supplemental oxygen should be administered. Apnea will last approximately for one minute. Opening the airway and bag-mask ventilation may be necessary. The patient doesn’t need to be intubated unless the seizures are intractable, there are signs of aspiration, or the patient remains unconscious following the seizure.

- Magnesium sulfate 4-6 g IV bolus should be administered over 20 min, followed by an infusion at 1-2 g/h.2 If the patient is already on magnesium, a 2g IV bolus should be administered.

- Small doses of midazolam or propofol may be used if the seizure is not terminating.

- Other causes of seizures, such as hypoglycemia and epilepsy, should be ruled out.

Labor Analgesia

- Neuraxial analgesia is preferred as it can counteract hypertension caused by pain and can minimize the risk of needing general anesthesia in the setting of cesarean delivery.

- Laboratory values should be trended prior to placement and removal of the epidural catheter with a goal platelet count of 70,000/mm.3

Cesarean Delivery

- Neuraxial anesthesia is preferred.

- If general anesthesia is required, adequate analgesia should be administered to abate hypertensive response of laryngoscopy.

- Magnesium sulfate may prolong neuromuscular blockade or contribute to delayed emergence.

- Methylergonovine is contraindicated in the setting of uterine atony.

HELLP Syndrome

- HELLP syndrome is defined as hemolysis, elevated liver enzymes, and low platelet count.

- Clinical presentation is commonly right upper quadrant pain, nausea, vomiting, headache, hypertension, proteinuria, etc.

- Management includes delivery, administration of magnesium and antihypertensive medications (as above) and following trends in platelet counts prior to a neuraxial procedure.2

- Complications include liver rupture, DIC, hemorrhage, and death.

References

- Hypertension in pregnancy. Report of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists’ Task Force on Hypertension in Pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2013;122(5):1122-31. PubMed

- Dyer R, Swanevelder J, Bateman B. Hypertensive disorders. In: Chestnut DH, ed. Chestnut’s Obstetric Anesthesia: Principles and Practice. Sixth Edition. Elsevier; 2019.

- Powe CE, Levine RJ, Karumanchi SA. Preeclampsia, a disease of the maternal endothelium: the role of antiangiogenic factors and implications for later cardiovascular disease. Circulation. 2011;123(24):2856-69. PubMed

- Koopmans CM, Bijlenga D, Groen H, et al. Induction of labour versus expectant monitoring for gestational hypertension or mild pre-eclampsia after 36 weeks' gestation (HYPITAT): a multicentre, open-label randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2009;374(9694):979-88. PubMed

- Publications Committee, Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine, Sibai BM. Evaluation and management of severe preeclampsia before 34 weeks' gestation. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2011;205(3):191-8. PubMed

Other References

- Smith KA. Expectant management of the patient with preeclampsia. OA-SOAP Fellows Webinar Series. 2016. Link

Copyright Information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.