Copy link

Hemorrhagic Shock in Trauma

Last updated: 03/22/2023

Key Points

- Initially, treat localized hemorrhage by applying pressure, sutures, or other mechanical compression/manipulation to temporize the bleeding.1

- If transfusion is indicated, give blood products as soon as available. Minimize crystalloid infusion (to 1 liter crystalloid) while awaiting blood products. Administer crystalloids only to resuscitate hypotensive patients towards goal-directed blood pressures.

- While type and crossmatched blood is ideal, emergency release, massive transfusion protocols or whole blood may be administered as alternatives.

Classification of Hemorrhagic Shock

- Massive hemorrhage is the most common cause of shock in trauma patients and is second only to traumatic brain injury as the leading cause of death in trauma patients.1

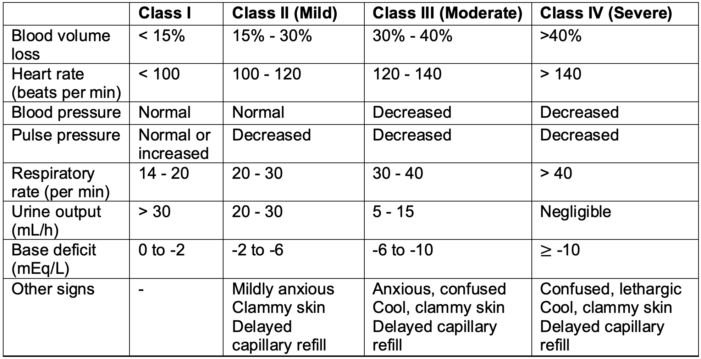

- Advanced Trauma Life Support®-10 has an updated classification for hemorrhagic shock that includes new categories for pulse pressure and base deficit (Table 1).2

Table 1. Updated classification of hemorrhagic shock by Advanced Trauma Life Support®-10 from the American College of Surgeons.2

Initial Assessment and Interventions

The initial management of trauma patients with hemorrhage should be focused on:

Control of Compressible or Extremity Bleeding (Stop the Bleed)

- Direct pressure can help control blood loss from compressible external wounds.

- Running and interrupted sutures help control sites of external bleeding if direct pressure is insufficient.

- Clamping blood vessels is an acceptable method of hemostasis if the bleeding vessels are visualized. Blind clamping of vessels should not be performed.1

- Tourniquets may be used in cases of amputation or severe extremity injury. These are often released every 45 minutes to avoid prolonged limb ischemia.1

- Pelvic stabilization is important for unstable pelvic fractures, which are associated with vascular injuries and massive hemorrhage. Pelvic stabilization can be achieved by either applying a circumferential pelvic binder or tying a sheet firmly around the pelvis.1

Control of Noncompressible Bleeding

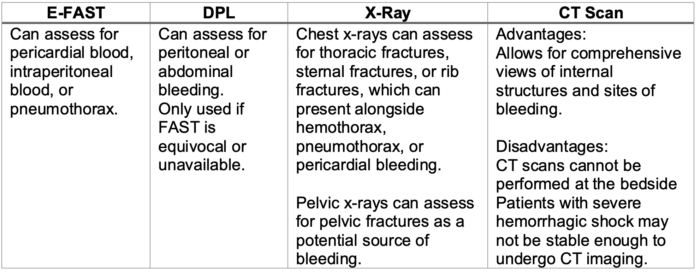

- Various modalities can be used to identify the source of internal bleeding and guide further management (Table 2).

Table 2. Modalities to identify the sites of internal blood loss. E-FAST = Extended focused assessment with sonography for trauma; DPL = diagnostic peritoneal lavage; CT = computed tomography.

Obtain Vascular Access

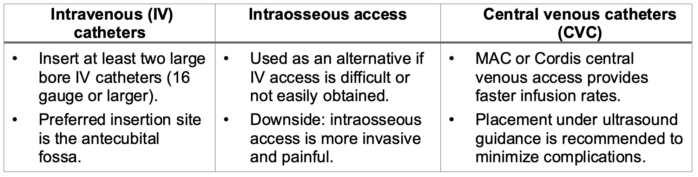

- Options for vascular access are listed in Table 3.

Table 3. Options for vascular access.

Restore Intravascular Volume

- Minimize the administration of intravenous crystalloids during the resuscitation of trauma patients and transfuse blood products as soon as available.

- If blood products are not immediately available, administration of 500 mL boluses of isotonic balanced crystalloids, such as lactated Ringer’s solution, may be considered.1

- In patients requiring massive transfusion, crystalloid resuscitation in a ratio greater than 1.5:1 per unit of pRBC transfusion was independently associated with worse outcomes, including a 70% higher risk of multi-organ failure and over a two-fold higher risk of acute respiratory distress syndrome and abdominal compartment syndrome.3

- Administration of large volumes of crystalloids (more than 1.5L) has been shown to be an independent risk factor for mortality in trauma patients, especially in elderly patients.4

- Early use of vasopressors may be harmful in hemorrhagic shock. However, vasopressors may be useful in cases of hemorrhagic shock with spinal cord injury.1 In spinal cord injury cases, norepinephrine is the preferred vasopressor.

Transfuse Blood Products

- If transfusions are indicated, blood products should be given as soon as possible to avoid hypotension and to minimize crystalloid administration.

- Transfuse packed red blood cells (pRBC), fresh frozen plasma (FFP), and platelets in a 1:1:1 ratio to avoid coagulopathy in damage control resuscitation.

- If using aphaeresis platelets, transfuse pRBC, FFP, and aphaeresis platelets in a 6:6:1 ratio.

- While using type and crossmatched blood products is ideal, they can require significant time to prepare. If necessary, type-specific blood or emergency-release blood can be used. Girls and women of childbearing age should be administered O-negative blood, while O-positive blood can be administered in all men and in women in whom childbearing is not a consideration.

- Low titer group O-negative whole blood can also be used if available.

- Thromboelastography (TEG), rotation thromboelastometry (ROTEM), or other point-of-care coagulation assessments should be used to guide trauma resuscitation.

Predicting the Need for Massive Transfusion Protocol (MTP)

- Massive transfusion is defined as transfusing 10 units pRBC over 24 hours.

- Early identification of the need for MTP is associated with improved outcomes.

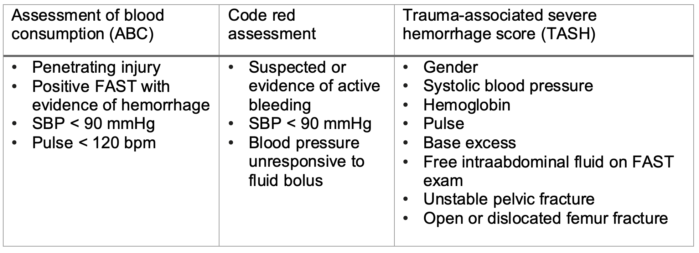

- Identifying the need for MTP is often dependent on clinical judgment and aided by several scoring assessments (Table 4).1

Table 4. Examples of scoring systems to identify the need for massive transfusion.1

Management of Severe Ongoing Hemorrhage

- Avoid hypothermia and minimize coagulopathy risks

- Increase the ambient temperature in the trauma bay

- Cover the patient in warm blankets

- Use warm IV fluids and blood products

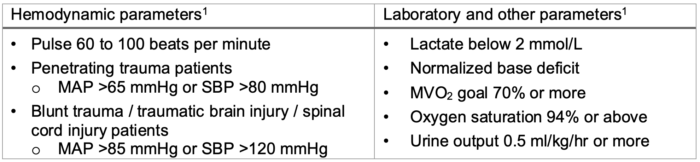

- The patient’s hemodynamics, lactate, and other laboratory parameters should be continuously monitored to ensure adequate tissue perfusion (Table 5).

- Administration of tranexamic acid should be considered if the patient arrives within 3 hours of injury.1

Table 5. Monitoring hemodynamics and labs during prolonged resuscitation. MAP = mean arterial pressure; SBP = systolic blood pressure; MVO2 = mixed venous oxygen saturation.

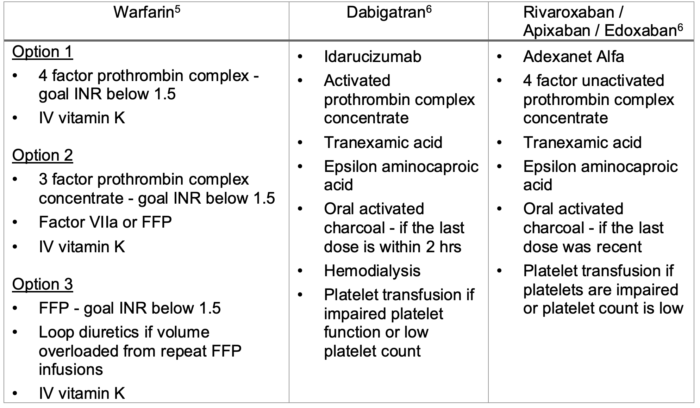

Reverse Anticoagulation

- In patients on anticoagulant therapy with life-threatening bleeding, reversal of anticoagulation should be considered (Table 6).

Table 6. Reversal of anticoagulation for life-threatening bleeding.

References

- Colwell C. Initial management of moderate to severe hemorrhage in the adult trauma patient. In: Moreira ME, ed. UpToDate; 2022. Accessed December 19th, 2022.

- Galvagno SM, Nahmias JT, Young DA. Advanced trauma life support Update 2019. Management and applications for adults and special populations. Anesthesiology Clin. 2019; 37(1):13-32. PubMed

- Neal MD, Hoffman MK, Cuschieri P, et al. Crystalloid to packed red blood cell transfusion ratio in the massively transfused patient: when a little goes a long way. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2012; 72(4):892-8. PubMed

- Ley EJ, Clond MA, Srour MK, et al. Emergency department crystalloid resuscitation of 1.5 L or more is associated with increased mortality in elderly and nonelderly trauma patients. J Trauma. 2011; 70(2):398-400. PubMed

- Hull RD, Garcia DA. Management of warfarin-associated bleeding or supratherapeutic INR. In: Leung LLK, ed. UpToDate; 2022. Accessed December 19th, 2022.

- Garcia DA, Crowther M. Management of bleeding in patients receiving direct oral anticoagulants. In: Leung LLK, Moreira ME, eds. UpToDate; 2022. Accessed December 19th, 2022.

Copyright Information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.