Copy link

Fresh Frozen Plasma

Last updated: 06/21/2024

Key Points

- Fresh frozen plasma (FFP) is the acellular portion of a whole blood collection that contains all coagulation factors.

- Plasma products can be used to improve hemostasis in the setting of multiple coagulation factor deficiencies.

- Transfusing 10-15 mL/kg of plasma will increase coagulation factors by approximately 20%.

- Laboratory evidence of coagulopathy should be obtained prior to transfusing plasma.

Introduction

- Plasma has been utilized to improve hemostasis as early as the 1930s, but early use was plagued by issues with preparation, storage, and contamination.1

- Plasma is the acellular portion of blood and contains most plasma proteins, including coagulation factors, fibrinolytic proteins, albumin, and immunoglobulins.2

- Currently, commonly used plasma products include FFP, plasma frozen within 24 Hours after phlebotomy (PF24), and thawed plasma.

Plasma Preparations

Fresh Frozen Plasma

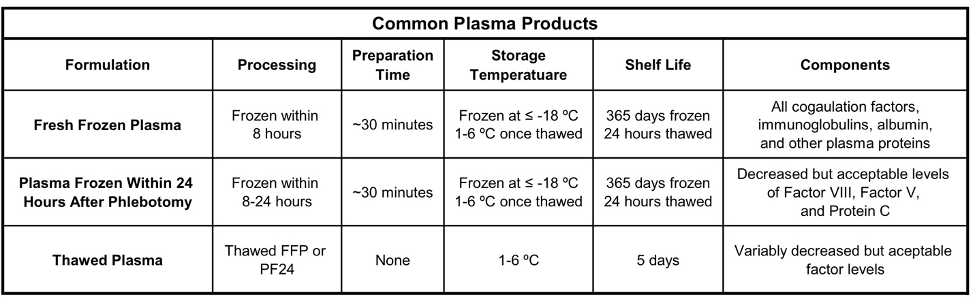

- After separation from a whole blood collection or collected from apheresis, FFP is frozen at ≤ -18°C within 8 hours of collection (Table 1).

- An average unit contains 200-250 mL but can be variable depending on the collection method.

- FFP can be stored frozen for up to 1 year in a citrate-containing anticoagulant solution.3

- FFP must be thawed for ~30 minutes prior to use1 and can be stored at 1-6 ºC for up to 24 hours after thawing.

- FFP contains all coagulation factors, including normal levels of factors V and VIII.3

Plasma Frozen Within 24 Hours After Phlebotomy

- Derived from methods similar to FFP, PF24 is frozen and stored within 24 hours after collection (Table 1).

- It was developed to allow time for human leukocyte antigen (HLA) testing to exclude high-risk samples and to decrease the incidence of transfusion-related acute lung injury.1

- Storage methods and time frames are similar to FFP.

- Levels of factor VIII4 and protein C are reduced, while levels of factor V are variable compared to FFP.3

- PF24 can be used interchangeably with FFP in most situations.4

Thawed Plasma

- Once the 24-hour thawed storage time for FFP and PF24 is reached, the collection may be relabeled as thawed plasma (Table 1).

- Thawed plasma may be stored at 1-6°C for an additional 4 days.3

- Studies have shown that coagulation factors remain in therapeutic ranges with the largest decreases in factors VIII and V, and thawed plasma may be used in place of FFP in most situations.5

- The use of thawed plasma increases the available plasma supply and may be beneficial in emergent settings as thawing time is not required.

Table 1. Commonly used plasma products and their attributes. Adapted from Watson JJJ, et al. Plasma Transfusion: History, Current Realities, and Novel Improvements. Shock. 2016;46(5):468-79.

Clinical Uses

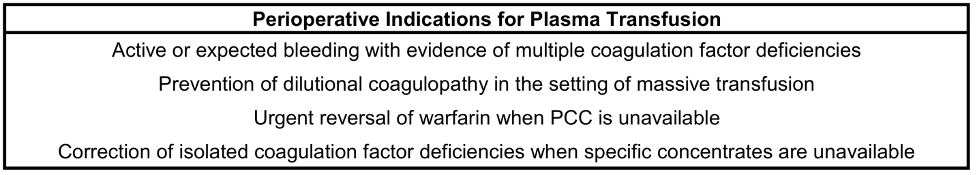

- According to the 2015 American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) practice guidelines for perioperative blood management,6 the indications for plasma transfusion include:

- For the correction of excessive microvascular bleeding with an international normalized ratio (INR) > 2.0 in the absence of heparin use.

- For the correction of excessive microvascular bleeding due to coagulation factor deficiencies in patients transfused with more than 1 blood volume when coagulation labs cannot be rapidly obtained.

- For the urgent reversal of warfarin when prothrombin complex concentrate (PCC) is unavailable.

- For the correction of known coagulation factor deficiencies when specific concentrates are unavailable.

- Generally, FFP transfusion is indicated for active bleeding in the setting of multiple factor deficiencies. This can include situations with decreased factor production (e.g., liver disease), increased factor consumption (e.g., disseminated intravascular coagulation), and to prevent dilutional coagulopathy during massive transfusion.3

- Other indications include the treatment of thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura or in the setting of plasma protein deficiencies (e.g., C1 inhibitor deficiency) when recombinant products are unavailable.3

- The ASA practice guidelines also recommend obtaining coagulation tests (PT/INR and aPTT) prior to FFP transfusion if possible.6 It is generally not recommended to administer FFP to correct a mildly elevated INR in the absence of bleeding, as FFP does not correct minimally elevated INR values below 1.85.

- The use of viscoelastic assays such as thromboelastography (TEG) to guide the transfusion of FFP may help decrease complications and reduce product use.7

Table 2. Indications for the appropriate use of perioperative plasma transfusions.

Administration

- Recommendations for dosing of FFP are 10-15 mL/kg with a goal of increasing coagulation factor levels to 30% of normal.6 Some studies have shown that higher dosing (up to 30 mL/kg) may be required to achieve this goal, especially in those with liver disease.8

- FFP should be administered through a blood administration set with a 170–200-micron filter.

- Because plasma contains antibodies, plasma products should be ABO-identical or ABO-compatible for safe administration.3 Despite these recommendations, there is data suggesting ABO-compatible plasma increases morbidity compared to ABO identical plasma.9 RhD compatibility is not necessary.3

Complications

Febrile and Allergic Reactions

- Mild symptoms of febrile or allergic reactions include fever, chills, and urticaria.

- These reactions occur during 1-3% of transfusions.

- Rare anaphylactic reactions can occur, the most notable cause being IgA-deficient recipients.

- Treatment is symptomatic.1

Transfusion-Associated Circulatory Overload (TACO)

- TACO is due to volume overload, resulting in cardiogenic pulmonary edema.

- The incidence of TACO is reported in up to 11% of transfusions.

- Symptoms include respiratory distress, hypertension, and peripheral edema.

- Treatment includes volume reduction with diuresis and ventilatory support if necessary.2

- Reducing the infusion rate may help with prevention.

Transfusion-Related Acute Lung Injury (TRALI)

- TRALI is an acute lung injury occurring within 6 hours of transfusion.

- Signs and symptoms include respiratory distress, acute hypoxemia, and pulmonary edema.

- Treatment is supportive and may require invasive or non-invasive ventilation.

- Prevention strategies include using plasma from male or never pregnant female donors and using plasma that has been screened for HLA antibodies.1

- Please see the OA summary on blood transfusion reactions for more details. Link

Citrate Toxicity

- Plasma products contain a citrate anticoagulant solution in a larger concentration than red blood cell products.

- Citrate binds calcium and magnesium, and which can lead to symptoms of hypocalcemia including hemodynamic instability.6

- Citrate toxicity is more common in the setting of large volume transfusion, liver disease, kidney disease, or in the pediatric population.3

Infection

- Viral transmission is a rare complication of plasma transfusion.

- Blood donations are tested for various infectious agents, including human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), hepatitis C virus (HCV), and hepatitis B virus (HBV).

- According to 2011 FDA data, transmission risks of a unit of blood are as follows:10

- HIV-1 and -2 – 1:1,476,000

- HCV – 1:1,149,00

- HBV – 1:280,000

- Intracellular viral transmission (e.g., cytomegalovirus, human T-cell leukemia virus) is decreased in plasma products.

- Please see the OA summary on blood transfusion complications for more details. Link

References

- Watson JJJ, Pati S, Schreiber MA. Plasma transfusion: History, current realities, and novel improvements. Shock. 2016;46(5):468-79. PubMed

- Kor DJ, Stubbs JR, Gajic O. Perioperative coagulation management – fresh frozen plasma. Best Pract Res Clin Anaesthesiol. 2010;24(1):51-64. PubMed

- Association for the Advancement of Blood & Biotherapies ARC, America’s Blood Centers, Armed Services Blood Program. Circular of Information for the Use of Human Blood and Blood Components. Plasma Components 2021. p. 8, 19-27. Link

- O'Neill EM, Rowley J, Hansson-Wicher M, et al. Effect of 24-hour whole-blood storage on plasma clotting factors. Transfusion. 1999;39(5):488-91. PubMed

- Downes KA, Wilson E, Yomtovian R, et al. Serial measurement of clotting factors in thawed plasma stored for 5 days. Transfusion. 2001;41(4):570. PubMed

- Practice guidelines for perioperative blood management: An updated report by the American Society of Anesthesiologists task force on perioperative blood management. Anesthesiology. 2015;122(2):241-75. PubMed

- Holcomb JB, Minei KM, Scerbo ML, et al. Admission rapid thrombelastography can replace conventional coagulation tests in the emergency department: Experience with 1974 consecutive trauma patients. Annals of Surgery. 2012;256(3):476-86. PubMed

- Youssef WI, Salazar F, Dasarathy S, et al. Role of fresh frozen plasma infusion in correction of coagulopathy of chronic liver disease: A dual phase study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98(6):1391-4. PubMed

- Shanwell A, Andersson TM, Rostgaard K, et al. Post-transfusion mortality among recipients of ABO-compatible but non-identical plasma. Vox Sang. 2009;96(4):316-23. PubMed

- Dudley M, Turnbull, JH; Miller, RD. Patient blood management: Transfusion therapy. In: Michael A. Gropper LIE, Lee A. Fleisher, Jeanine P. Wiener-Kronish, Neal H. Cohen, Kate Leslie, ed. Miller’s Anesthesia. 9th ed. Elsevier; 2020:1546-78.

Copyright Information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.