Copy link

Epidermolysis Bullosa

Last updated: 04/18/2024

Key Points

- Epidermolysis bullosa (EB) is a group of disorders caused by genetic mutations in genes encoding structural proteins responsible for adhesion within varying layers of the dermoepidermal junction.1

- While EB is most known for its dermatologic presentation, a multidisciplinary approach is essential as it affects multiple organ systems.

- Friction and shearing forces to the skin are responsible for new bullae and wound formation, while direct pressure or compressive forces are better tolerated.1

- A thorough preanesthesia evaluation, as well as special attention to positioning, monitoring, and airway management, are required to minimize trauma during the anesthetic care of EB patients.

Introduction

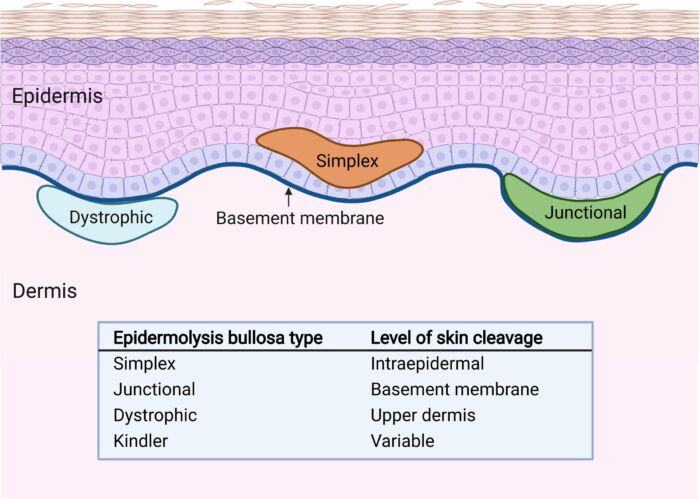

- EB is classified into four main types based on the structural location of blistering (Figure 1).2

- All forms of the disease have skin fragility in common, resulting in blisters and erosions and often secondary infections.3

- Mild shearing forces cause blisters and wounds.4

Figure 1. Types of EB based on the location of blister formation within the dermoepidermal junction. Reproduced with permission from Mittal BM, et al. Anesthetic management of adults with epidermolysis bullosa. Anesth Analg. 2022.

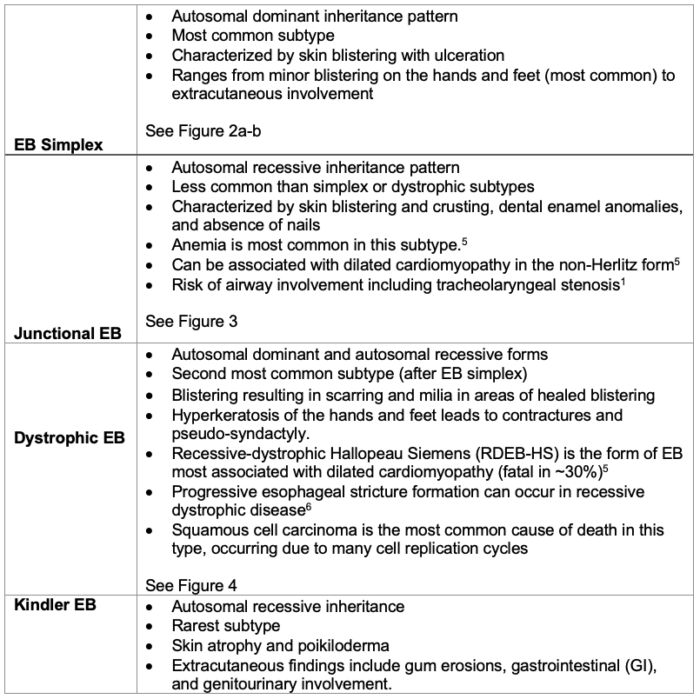

Subtypes of EB

Table 1. Subtypes of EB

Figure 2a. Blisters and erosions are common in surfaces including the hands (left image), feet, elbows, and knees (right image). Courtesy of Bryan Williams DDS, MSD. Seattle Children’s Hospital.

Figure 3. Pediatric patient with junctional EB undergoing dental cleaning. EB patients are at high risk for dental caries due to poor adherence between the tooth enamel and dentin. Courtesy of Bryan Williams DDS, MSD. Seattle Children’s Hospital.

Figure 4. Dystrophy of the nails, pseudo-syndactyly, generalized blisters and scarring seen in dystrophic EB. Photos property of L. Furukawa, MD. Lucile Packard Children’s Hospital Stanford.

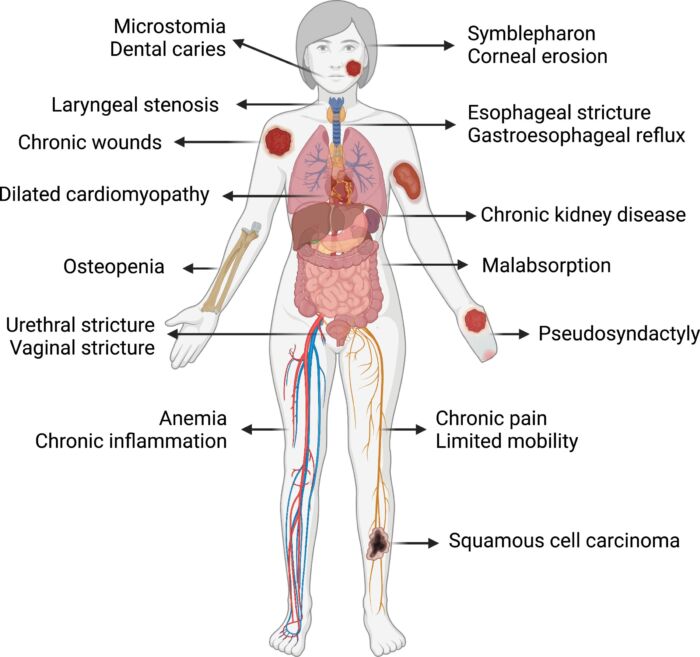

Extracutaneous Manifestations3,4,6

The etiology of dilated cardiomyopathy remains unknown. Selenium or carnitine deficiencies may be involved.

Anemia is multifactorial due to blood loss, iron deficiency, protein loss from open wounds, and erosions in the GI tract impacting nutritional absorption.

Figure 5. Examples of extracutaneous involvement of dystrophic type EB. Reproduced with permission from Mittal BM, et al. Anesthetic management of adults with epidermolysis bullosa. Anesth Analg. 2022.

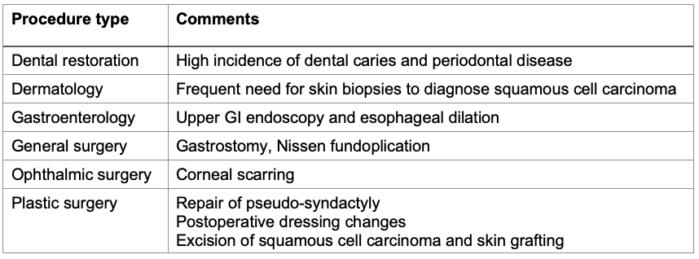

Common Procedures and Indications1,6

Table 2. Common procedures in EB patients

Figure 6. An anesthetized pediatric patient with EB preparing to undergo dental evaluation and treatment. Courtesy of Bryan Williams, DDS, MSD. Seattle Children’s Hospital.

Preanesthesia Evaluation1,3,4,6

Prior to Procedure

- In-person evaluation in the preanesthesia clinic is preferred. A history of pain medication usage or chronic pain management can help guide perioperative pain management.

- Previous anesthetic records should be reviewed, with special attention to airway-related challenges (e.g., ease of mask ventilation, degree of laryngeal involvement, techniques utilized).

- A targeted physical exam should be performed with particular attention to skin involvement and airway (mouth opening or inter-incisor distance, ankyloglossia). Photographic documentation of anatomical findings in the secure electronic medical record can be helpful.

- Additional preoperative testing (echocardiography, labs) may be recommended in high-risk subtypes; consider targeted testing based on any new extracutaneous manifestations.

- A systems-based, interdisciplinary approach should be used to examine the goals of the procedure as related to patient quality of life and acceptable risks.

- Operating room (OR) time should be scheduled appropriately, expecting anesthesia and surgery to take longer than usual due to extra precautions to protect the skin and mucosa.

Day of Procedure

- Identify potential sites for IV cannulation.

- Inquire about sensitive areas that may require extra attention for positioning/padding.

- Specify preferences for moving the patient and securing equipment and monitors.

Approach to Airway Management

Airway Considerations

- Microstomia and ankyloglossia can limit mouth opening and jaw movement.6

- Neck extension is often limited from contractures.

- Laryngeal or glottic stenosis is possible from prior airway manipulations.

- Nasal passages are lined with respiratory epithelium, which is less likely to blister than the stratified squamous epithelium of oral mucosa.6

- More involvement of respiratory columnar epithelium is seen in junctional EB.

Equipment Recommendations

- Lubricate all airway instruments to minimize trauma (facemask, nasal cannula, endotracheal tube (ETT), laryngoscope blade)

- Always prepare for a difficult intubation and have fiberoptic bronchoscope readily available

- Choose a cuffed ETT 0.5-1.0 size smaller than predicted and maintain low cuff pressure1

- If a supraglottic airway is necessary, use a size smaller and avoid overinflation.1

Figure 7. Ankyloglossia, reduced inter-incisor distance, and a retroflexed epiglottis in recessive dystrophic EB. Reproduced with permission from Mittal BM, et al. Transnasal humidified rapid insufflation ventilatory exchange for difficult airway management in adults with recessive dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa: A Case Series. AA Pract. 2022.

Figure 8. Specialized nonadhesive dressings are moistened and applied to provide a barrier between the patient’s skin and areas that will come in contact with the proceduralist’s hands or instruments. Eyes are lubricated and protected. Courtesy of Bryan Williams DDS, MSD. Seattle Children’s Hospital.

- Mask ventilation is typically performed easily, but intubation can be challenging.6

- When appropriate, a natural airway should be considered with a nasal cannula, facemask, or blowby oxygen.6

- Supraglottic airway use should be avoided due to the risk of mouth and airway blistering and should only be considered in the case of an emergency.6

- Direct laryngoscopy is usually straightforward in the first few years of life.6

- Asleep, spontaneously breathing fiberoptic technique is often preferred, even in patients with severe disease, as they are likely to remain an easy mask.

- The nasal mucosa is often spared compared to the oral mucosa, making nasal fiberoptic intubation potentially less traumatic.

- Knowing the EB subtype and its impact on the choice of intubation technique is critical.1

- Direct laryngoscopy followed by oral intubation can typically be performed in recessive dystrophic type without laryngeal bullae formation, postoperative stridor, or airway obstruction.1

- A nasotracheal tube via fiberoptic technique should be considered in more severe subtypes.

- After extubation, the airway should be inspected for trauma.

Perioperative Considerations & Management

Choice of Anesthetic Techniques

- General, neuraxial and regional can be performed safely in EB patients.6

- Must be individualized depending on the patient, EB subtype, and surgery/procedure type.

OR Preparation

- Warm the OR to reduce heat loss due to skin lesions and low body mass index. However, some patients may lose their eccrine sweat glands due to scarring and can be prone to overheating.

- Consider the use of a Megadyne brand pad for surgeries requiring electrocautery as a traditional adhesive Bovie-brand pad cannot be used.

- Instruct staff to minimize physical contact with the patient.

- Consider preparing an EB anesthesia kit with specialized supplies and easily retrieved by anesthesia technician prior to anesthetic care

Vascular Access4

- Inquire with patient and family about sites of previous success

- Consider ultrasound guidance for vascular access. Patients will often have visible targets due to their thin skin.

- Avoid any friction while cleansing the skin and avoid using a tourniquet unless it is over a dressing.

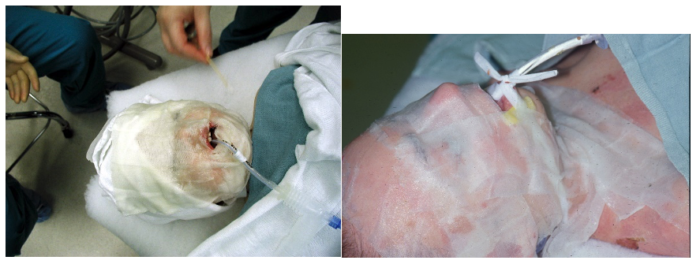

- Silicone-based, low tack adhesive dressings can be used to secure the IV. Other methods for securement include wrapping or suturing lines in place.

Figure 9. IV placement with direct pressure of a hand used instead of a tourniquet (left image). Courtesy of Bryan Williams DDS, MSD. Seattle Children’s Hospital. Securement of an IV using Webril® padding underneath a Coban wrap (right image), property of L. Furukawa, MD, Lucile Packard Children’s Hospital Stanford.

Positioning & Monitors1,6

- The OR table should be padded to reduce trauma from movement.

- For patient transfer, nonfriction methods should be used, such as levitating on draw sheet, or allow the patient to move themselves.

- Extremities should be placed in a neutral position because of the contractures.6

- Adhesives should be avoided and specialized dressings/tapes should be used that do not cause friction when applied or removed such as soft silicone tape (Mepitac), nonadherent mesh dressing (Mepitel), and absorbent foam dressing (Mepilex).1

- Self-adherent wrap (Coban) with minimal tension can be utilized to wrap monitors around patient

- Based on the intubation approach, cotton wrap can be tied gently around the ETT and patient’s neck (oral ETT, Fig. 8) or surgical towels and head wrap (nasal ETT) can be used for securement

- A clip style pulse oximeter can be used. Alternatively, a Tegaderm can be applied over the adhesive surface prior to application.

- ECG leads can be placed on a nonadhesive gel defibrillator pad.6

- Blood pressure cuffs can be placed over cotton padding (Webril®).

- Attention should be paid to skin and mucosal protection. Eye lubrication is important as the eyelids cannot be taped shut and often do not close in repose.

Figure 10. Securement of a pulse oximeter (left image) and a blood pressure cuff (middle image) by utilizing padding beneath the monitor and ensuring no adhesives come in contact with the skin. Use of a nonadhesive gel defibrillator pad between adhesive ECG lead and patient skin. Left and middle images, courtesy of Bryan Williams DDS, MSD, Seattle Children’s Hospital. Right image, property of L. Furukawa, MD, Lucile Packard Children’s Hospital Stanford.

Induction & Maintenance1,6

- In addition to premedication such as oral midazolam, parental presence may be helpful during induction of pediatric patients.

- A preference for intravenous (IV) versus inhalation induction should be discussed with the patient. IV may be preferred to avoid facial trauma particularly during stage II (excitatory phase).

- The facemask should be lubricated well with petroleum jelly, and also consider applying a barrier to skin areas that will come in contact with the mask.6

- Avoid causing agitation that can lead to excessive movement and skin damage.6

- The need for neuromuscular blockade should be determined.

- Nondepolarizers may have a prolonged duration of action due to changes in the volume of distribution and hypovolemia.

- IV anesthetic technique may reduce agitation and emesis in the recovery period.

- Balanced anesthetic technique including regional anesthesia and IV adjuncts may optimize patient comfort and safety.6

Emergence & Postoperative Care1,6

- Agitation and uncontrolled movement including coughing and gagging should be avoided.

- The advantages of deep extubation should be weighed against the risk of aspiration and laryngospasm.

- The mouth may be suctioned with a soft suction catheter.

- Many EB patients live in chronic pain and may require higher doses of analgesics.

- Postoperative steroids should be considered to reduce airway injury and swelling.

- Appropriate wound care should be ensured, including surveillance for new postoperative wounds.

References

- Nandi R, Howard R. Anesthesia and epidermolysis bullosa. Dermatol Clin. 2010;28(2):319-24. PubMed

- Has C, Bauer JW, Bodemer C, et al. Consensus reclassification of inherited epidermolysis bullosa and other disorders with skin fragility. Br J Dermatol. 2020;183(4):614-27. PubMed

- Fine JD, Johnson LB, Weiner M, et al. Gastrointestinal complications of inherited EB. Cumulative experience of the national epidermolysis bullosa registry. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2008;46(2):147-58. PubMed

- Brooks-Peterson M, Strupp KM, Brockel MA, et al. Anesthetic management and outcomes of patients with epidermolysis bullosa: Experience at a tertiary referral center. Anesth Analg. 2022;134(4):810-21. PubMed

- Hall M, Weiner M, Li K, Suchindran C. Risk of Cardiomyopathy in Inherited Epidermolysis Bullosa. Journal of Dermatology. 2008; 159(3):677-682. PubMed

- Mittal BM, Goodnough CL, Bushell E, et al. Anesthetic management of adults with epidermolysis bullosa. Anesth Analg.2022;134(1):90-101. PubMed

- Goldschneider K, Lucky AW, Mellerio JE, et al. Perioperative care of patients with epidermolysis bullosa. Paediatr Anaesth. 2010;20(9):797-804. PubMed

Copyright Information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.