Copy link

Controversies in Pediatric Regional Anesthesia

Last updated: 02/02/2024

Key Points

- The numerous benefits of regional anesthesia in children greatly outweigh the risks and the safety profile is very high.

- Regional blocks should preferably be performed under anesthesia or deep sedation in children to avoid postoperative complications.

- There is no evidence that regional anesthesia increases the risk of acute compartment syndrome or delays its diagnosis.

- The use of local anesthetic test dosing remains discretionary because of the difficulty in interpreting a negative test dose.

Introduction

- Orthopedic surgeries are major indications for regional anesthesia in children and adults. However, there are notable differences in the distribution of cases between the two groups. Orthopedic surgeries in children mostly involve injuries (sports-related and otherwise) and repair of congenital abnormalities.1

- Ultrasound-guided techniques have allowed for the rapid expansion in the use of regional anesthesia in pediatric orthopedic surgeries.

- Several large multi-institutional databases have shown that pediatric regional anesthesia is extremely safe.1

- The Pediatric Regional Anesthesia Network (PRAN) reported no permanent neurologic deficits in more than 100,000 blocks. The risk of transient neurological deficit was 2.4/10,000 cases, and local anesthetic systemic toxicity was 0.76/10,000 cases. The most common adverse events were benign catheter-related failures.2

Benefits and Risks

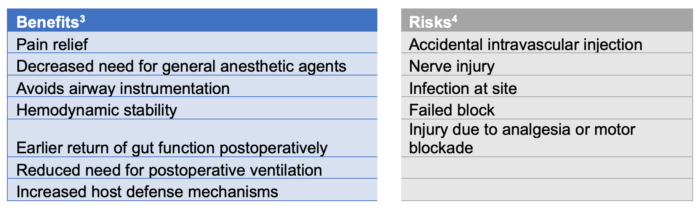

- As with any procedure, there are risks in using regional anesthesia; however, the benefits far outweigh the risks, given the high safety margin and minimal side effects (Table 1).

Table 1. Benefits and risks of regional anesthesia

Contraindications

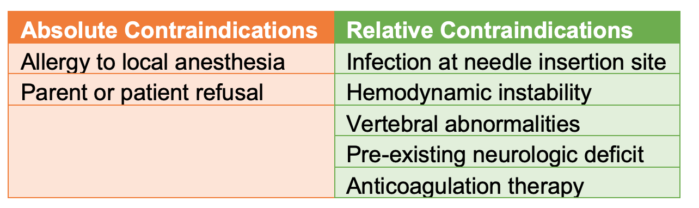

- The contraindications for performing regional anesthesia in children are listed in Table 2. Patients with relative contraindications should be evaluated individually to determine their eligibility.3 The patient’s age and neurological development should also be considered.

Table 2. Contraindications for performing regional anesthesia in children

Controversies

Awake versus Asleep Blocks

- Updated practice guidelines from the European Society of Regional Anesthesia (ESRA) and Pain Therapy and the American Society for Regional Anesthesia and Pain Medicine (ASRA) strongly recommend performing pediatric regional blocks under general anesthesia or deep sedation.5 This is mainly to decrease complications associated with poor patient cooperation and the potential risk of injuring neighboring structures due to sudden movements.

- In fact, PRAN data suggested that performing regional anesthesia in awake or lightly sedated children carries a minimally increased risk of postoperative neurologic symptoms, though this risk is extremely low due to advances in techniques that prevent intraneural and intravascular injection.1

- Despite the reassuring safety of pediatric regional blocks performed under general anesthesia or deep sedation, serious complications can still occur.5

Compartment Syndrome

- Though highly debated, no convincing evidence has been found between regional anesthesia and delayed diagnosis of acute compartment syndrome (ACS).1

- Conversely, regional anesthesia may actually allow for earlier detection of ACS. The mechanism of tissue injury in ACS is not muted by regional anesthesia. Further, the associated inflammatory markers may activate nociceptors that diminish the effects of local anesthetics. This is manifested by a sudden change in the patient’s pain experience that is out of proportion to what is expected with a well-placed block; this can be an early alarm to evaluate the patient for ACS.

- ESRA and ASRA guidelines recommend the following precautions to reduce the risk of ACS in children undergoing pediatric regional anesthesia.5

- Clinicians should use 0.1 to 0.25% bupivacaine, levobupivacaine, or ropivacaine for single-shot peripheral and neuraxial blocks because they are less likely to mask the ischemic pain of ACS.

- Clinicians should use 0.1% concentration of local anesthetics for continuous infusions (same reason).

- The concentration and volume of local anesthetics in sciatic catheters for tibial compartment surgery or other high-risk surgeries should be limited.

- Caution should be used with local anesthetic additives because they increase the duration and/or density of the block.

- The Acute Pain Service should closely monitor high-risk patients.

- Compartment pressures should be urgently measured if ACS is suspected.

Loss of Resistance (LOR)

- To identify the epidural space, both LOR to saline and LOR to air have been used and supported by different international experts. The use of saline with a bubble of air has also been proposed.

- Several complications related to the air-LOR technique have been published, including venous air embolism, nerve root compression, pneumocephalus, incomplete analgesia, etc.5

- In neonates and infants, the volume of air contained in the syringe should be limited to less than 1 mL, and air injections should not be repeated if multiple attempts are made to access the epidural space.5

Test Dose and Intravascular Injection

- There is considerable controversy and variability in practice regarding the use of local anesthetic (LA) test doses in children. Some clinicians add epinephrine to an LA solution at a concentration of 2.5 or 5 mcg/mL (concentration of 1 in 400,000 or 1 in 200,000, respectively).5 The volume of the LA test dose is typically 0.1 mL/kg.

- However, children have a higher resting heart rate. Also, most blocks are performed under general anesthesia, which can blunt the hemodynamic effects of epinephrine, which reduces the utility of the test dose. Therefore, a negative test dose is reassuring but does not rule out intravascular injection.5

- All injections of LA should be performed slowly, in small aliquots (0.1-0.2 mL/kg), and with intermittent aspiration and observation of the electrocardiogram tracing.5

- Any modification of the T wave or heart rate within 30 to 90 seconds after injection of a LA test dose should be interpreted as an accidental intravascular injection until disproven.5

Regional Anesthesia and Implanted Spinal Hardware

- Cerebral palsy patients with an intrathecal baclofen pump frequently present for hip reconstruction surgeries. However, these pumps are often considered a relative contraindication to regional anesthesia, especially neuraxial approaches.1

- Successful epidural catheter placement without major complications has been described in a case series of 16 children using a multidisciplinary approach and fluoroscopically guided epidural placement.6

References

- Alrayashi W, Cravero J, Brusseau R. Unique issues related to regional anesthesia in pediatric orthopedics. Anesthesiology Clinics. 2022;40(3):481-9. PubMed

- Walker BJ, Long JB, Sathyamoorthy M, et al. Complications in pediatric regional anesthesia: An analysis of more than 100,000 blocks from the Pediatric Regional Anesthesia Network. Anesthesiology. 2018; 129(4): 721-32. PubMed

- Bosenberg A. Benefits of regional anesthesia in children. Paediatr Anaesth. 2011;22(1):10-18. PubMed

- Polaner DM, Drescher J. Pediatric regional anesthesia: What is the current safety record? Paediatr Anaesth. 2010;21(7):737-42. PubMed

- Ivani G, Suresh S, Ecoffey C, et al. The European Society of Regional Anaesthesia and Pain Therapy and the American Society of Regional Anesthesia and Pain Medicine Joint Committee practice advisory on controversial topics in pediatric regional anesthesia. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2015;40(5):526-32. PubMed

- Eklund SE, Samineni AV, Koka A, et al. Epidural catheter placement in children with baclofen pumps. Paediatr Anaesth. 2021; 31(2): 178-85. PubMed

Copyright Information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.