Copy link

Congenital Heart Diseases and Pregnancy: Part 1

Last updated: 10/02/2025

Key Points

- If not contraindicated, neuraxial anesthesia, preferably a slowly administered epidural, is generally better tolerated than general anesthesia for most pregnant patients with congenital heart disease (CHD).

- Positive pressure ventilation should generally be avoided in these patients.

- It is important to arrange a multidisciplinary meeting prior to delivery to determine delivery mode, anesthetic plan, and any special monitoring antepartum, intrapartum, or postpartum.

Introduction

- Earlier diagnoses, better tests, and expanded treatment options for CHD have led to improved long-term survival.

- More women with CHD are reaching childbearing age. It is crucial to understand the implications of various CHD pathologies in the physiology of the parturient.

Cardiovascular Physiologic Changes of Pregnancy

- Changes in cardiac physiology during pregnancy can have significant ramifications in patients with CHD.

- Maternal blood volume increases by approximately 40%, and plasma volume increases by about 50%.1

- Maternal cardiac output (CO) also increases significantly by 30-50% during pregnancy.1

- The position of the mother is crucial for delivering CO.

- In the third trimester, when in a supine position, the gravid uterus can compress the vena cava, leading to a decrease in CO.1

- Heart rate rises during pregnancy by 10-20 beats per minute, and the vascular system undergoes remodeling due to the increased blood volume.1

- Both pulmonary vascular resistance and systemic vascular resistance (SVR) decrease, leading to an increase in pulmonary blood flow, as well as changes in the hemodynamics of the mother.1

Atrial Septal Defect (ASD)

Background and Pathophysiology

- ASD most commonly occurs in the ostium secundum in the interatrial septum that forms during the first 8 weeks of pregnancy.1

- Generally, patients with ASD remain asymptomatic until the 4th decade of life.1

Maternal and Fetal Considerations

- There is an increased risk of preeclampsia, atrial arrhythmias, fetal demise, and a small for gestational age fetus.1,2

- If the parturient does not have significant pulmonary hypertension secondary to their ASD, pregnancy is generally well tolerated.2

Anesthetic Considerations

- There is a higher risk of paradoxical embolism, which highlights the importance of de-airing lines.2

- Anesthesiologists can consider avoiding loss of resistance with air due to the theoretical risk of introducing air into veins while attempting to locate the epidural space.1

- For the higher risk group with severe pulmonary hypertension, it is important to maintain preload, and caution should be used with positive pressure ventilation due to decreased preload.1

Ventricular Septal Defect (VSD) with Left-to-Right Shunt

Background and Pathophysiology

- Most commonly (~80%), the interventricular defect is perimembranous.1

Maternal and Fetal Considerations

- It may be associated with an increased risk of preeclampsia.1

Anesthetic Considerations

- Generally well-tolerated1

- Echocardiography can be used to assess right-sided pressures and shunt fraction.1

VSD with Right-to-Left Shunt (Eisenmenger Syndrome)1,3

Background Pathophysiology

- Eisenmenger syndrome is characterized by the development of pulmonary hypertension resulting from increased shunting in the pulmonary circulation, ultimately leading to a reversal of the shunt from left to right to right to left.1

- The right-to-left shunt can lead to maternal hypoxemia.

Maternal and Fetal Considerations

- Eisenmenger syndrome is regarded as a contraindication to pregnancy because the mortality rate can reach as high as 50%.3

- This high mortality rate can be attributed to many factors (increased circulating blood volume, thrombotic complications, further strain on the right ventricle).

- A cesarean delivery or an assisted second-stage vaginal delivery may be preferred to prevent decreased preload during valsalva.

- Mortality most often occurs during the early postpartum period due to the sudden and dramatic hemodynamic changes after birth.4

Anesthetic Considerations

- While there are reviews and case reports that have shown a variety of anesthetic options, if not otherwise contraindicated, a slowly loaded epidural provides advantages in this population to maintain SVR.1

- General anesthesia carries risks of decreasing SVR, and these parturients may struggle with sudden changes in heart rate and blood pressure.

- Intravascular volume should be maintained.

- With severe pulmonary hypertension, an arterial line and central venous pressure monitoring should be considered.

- Pulmonary vasodilators, including nitric oxide, should be considered.1

- There should be a very low threshold to monitor these patients in the intensive care unit (ICU) in the postpartum period because of an increased risk of heart failure, arrhythmias, hypoxia, and pulmonary hypertension exacerbation.

- Delivery mode should be discussed in a multidisciplinary meeting involving maternal-fetal medicine, obstetric anesthesiology, and cardiology. If continuous telemetry monitoring is required during labor, the patient may need to deliver in an ICU setting.

- Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation can be an option for parturients who experience acute complications and/or have problems with oxygenation.

Patent Ductus Arteriosus

Background Pathophysiology

- Patent ductus arteriosus occurs when the ductus arteriosus remains open, allowing blood to flow from the aorta to the pulmonary artery.1

Maternal and Fetal Considerations

- It can cause additional strain on the heart and pulmonary hypertension.1

Anesthetic Considerations

- If the patient does not develop Eisenmenger syndrome, pregnancy and anesthesia are generally well tolerated.1

- Although rare, clinicians should consider performing a transthoracic echocardiogram to rule out pulmonary hypertension.1

Coarctation of the Aorta

Background Pathophysiology

- Narrowing of the aorta, usually just beyond the left subclavian artery

- This constriction restricts blood flow, leading to a pressure difference between the upper and lower body.

Maternal and Fetal Considerations

- Parturients with repaired coarctation generally tolerate pregnancy well.

- It can cause hypertension, aortic dissection, aortic rupture, and heart failure in those with unrepaired coarctation.1,5

Anesthetic Considerations

- It is important to screen before pregnancy if there is residual coarctation and for other abnormalities often associated with coarctation, such as a bicuspid aortic valve.5

- Neuraxial techniques should be considered, and depending on severity, a slowly administered epidural may be preferred over a single-shot spinal, with careful attention to ensuring adequate SVR.1

Fontan Physiology1,6

Background Pathophysiology

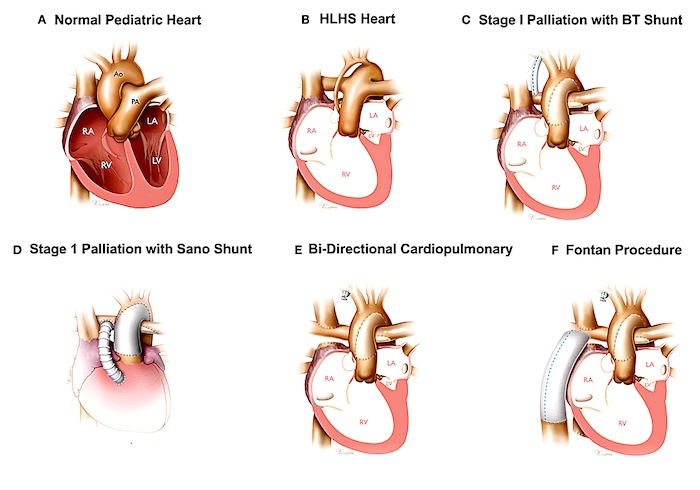

- Surgical connections direct systemic venous blood straight to the pulmonary arteries, bypassing the heart (Figure 1).

- The Fontan procedure is performed for valvular defects such as tricuspid atresia and for patients with a single ventricle physiology.

- Without a right ventricle, blood passively flows from the systemic veins to the lungs, relying solely on the central venous pressure.

Figure 1. Surgical correction of hypoplastic left heart syndrome resulting in Fontan circulation. Source: Wikimedia Commons. Bria AK, et al. Link

Maternal and Fetal Considerations

- There is a high incidence of arrhythmias, often supraventricular, due to atrial scar tissue.6

- The parturient’s functional status is at risk of declining during pregnancy, especially during labor and delivery.7

Anesthetic Considerations

- It is critical to ensure adequate intravascular volume. Both excessively low and high preload levels can be poorly tolerated.1,7

- Neuraxial anesthesia is preferred over general anesthesia to avoid positive pressure ventilation in a patient with a compromised right ventricle.1

- Telemetry monitoring may be needed during labor and delivery, which could require delivery in an ICU.

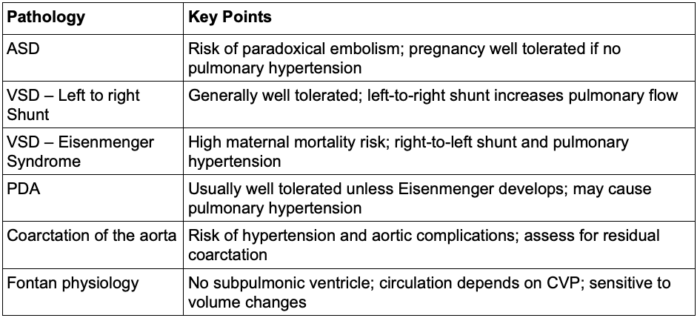

Table 1. Congenital heart defects: part 1 summary.

Abbreviations: VSD, ventricular septal defect; ASD, atrial septal defect; PDA, patent ductus arteriosus; CVP, central venous pressure

References

- Chestnut D, Wong C, Tsen L, et al. Chestnut’s Obstetric Anesthesia: Principles and Practice. 6th Edition, April 2019.

- Bredy C, Mongeon FP, Leduc L, Dore A, Khairy P. Pregnancy in adults with repaired/unrepaired atrial septal defect. J Thorac Dis. 2018;10(Suppl 24):S2945-S2952. PubMed

- Harris IS. Management of pregnancy in patients with congenital heart disease. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 2011;53(4):305-311. PubMed

- Yuan SM. Eisenmenger Syndrome in Pregnancy. Braz J Cardiovasc Surg. 2016;31(4):325-329. PubMed

- Regitz-Zagrosek V, Roos-Hesselink JW, Bauersachs J, et al. 2018 ESC Guidelines for the management of cardiovascular diseases during pregnancy. Eur Heart J. 2018;39(34):3165–3241. PubMed

- Drenthen W, Pieper PG, Roos-Hesselink JW, et al. Outcome of pregnancy in women with congenital heart disease: a literature review. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007; 49:2303–2311. PubMed

- Canobbio MM, Warnes CA, Aboulhosn J, et al. Management of pregnancy in patients with complex congenital heart disease: a scientific statement for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2017;135(8):e50–e87. PubMed

Copyright Information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.