Copy link

Complex Regional Pain Syndrome

Last updated: 05/22/2025

Key Points

- Complex regional pain syndrome (CRPS) is a neuropathic pain disorder, usually affecting the distal limbs, characterized by pain, swelling, limited range of motion, vasomotor instability, skin changes, and patchy bone demineralization.

- The pain is not restricted to a nerve territory or dermatome, is disproportionate to the degree of tissue injury, and persists beyond the normal expected time for tissue healing.

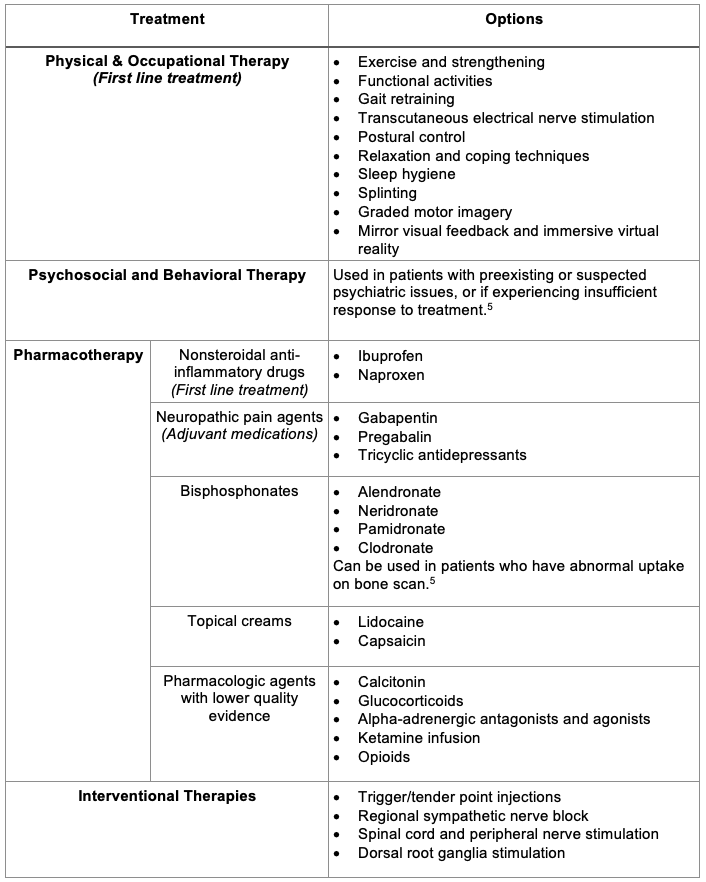

- Treatment is guided by a multidisciplinary approach. The first-line therapy includes physical therapy, occupational therapy, and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs).

Introduction and Pathogenesis

- CRPS is a neuropathic pain disorder, usually affecting the distal limbs, characterized by pain, swelling, limited range of motion, vasomotor instability, skin changes, and patchy bone demineralization.1,2 It often begins following a fracture, soft tissue injury, or surgery.

- A consensus definition of CRPS is as follows: “CRPS describes an array of painful conditions that are characterized by a continuing (spontaneous and/or evoked) regional pain that is seemingly disproportionate in time or degree to the usual course of any known trauma or other lesion. The pain is regional (not in a specific nerve territory or dermatome) and usually has a distal predominance of abnormal sensory, motor, sudomotor, vasomotor, and/or trophic findings. The syndrome shows variable progression over time.”2

- There are two subtypes of CRPS.1

- Type I CRPS (previously known as reflex sympathetic dystrophy) occurs in patients without evidence of peripheral nerve injury and represents approximately 90% of cases.

- Type II CRPS (previously known as causalgia) occurs when peripheral nerve injury is present.

- Clinically, they are indistinguishable and follow a regional rather than dermatomal or peripheral nerve distribution.3

- CRPS is further subdivided into “warm” or “cold,” and “sympathetically maintained or sympathetically independent,” which affect prognosis and treatment options.3

- The exact pathogenesis of CRPS remains unknown.1,3 Proposed mechanisms include:

- Inflammatory changes with the release of inflammatory mediators (tumor necrosis factor-alpha, interleukin 1b, 2, and 6) and pain-producing peptides (bradykinin, substance P, calcitonin gene-related peptide) by peripheral nerves

- Immunologic changes with autoantibodies against beta-2 adrenergic receptors, alpha 1a adrenergic receptors, and muscarinic-2 receptors

- Peripheral sensitization of the nervous system is triggered by the release of proinflammatory mediators.

- Central sensitization and maladaptive changes in pain perception at the central nervous system level. Increased excitability of the secondary dorsal horn neurons often occurs.

- Autonomic changes result from catecholamine hypersensitivity.

Epidemiology and Inciting Factors

- The estimated incidence of CRPS in the United States is 5-26 per 100,000 per year.

- CRPS is much more prevalent in women, with estimates of 2-4 times the rate in men. The incidence is highest in postmenopausal females.1

- The most common inciting factors for CRPS are fractures, crush injuries, sprains, surgeries, or carpal tunnel syndrome.1-3

- Other risk factors include fibromyalgia, rheumatoid arthritis, and psychological factors (depression and/or posttraumatic stress disorder).1,2

- The impact of genetics is unclear.3

Clinical Presentation

The main clinical findings of CRPS are listed below:

Pain

• Pain is the most common and debilitating symptom of CRPS. It is often described as a burning, stinging, or tearing sensation that is felt deep within the extremity in most cases.1

• The pain is often continuous and undulating but can be paroxysmal.

• It may be worse at night and exacerbated by limb movement, contact, heat/cold, or stress.1

• The pain is not restricted to a specific nerve territory or dermatome, is disproportionate to the degree of tissue injury, and persists beyond the normal expected time for tissue healing.

Sensory Abnormalities

• Hyperalgesia: increased sensitivity to pain; usual painful stimuli cause exaggerated pain.

• Allodynia: pain is experienced in response to stimuli that are typically not painful (light touch, temperature changes, etc.).

• Hypesthesia: decreased capacity for physical sensation

• These sensory disturbances are usually distal in the extremity, often in a glove/stocking pattern.

Motor Symptoms

• Decreased grip strength or tip-toe standing is present in approximately two-thirds of patients with CRPS.

• Limb movement may be limited by pain, edema, or contractures.

• Central manifestations such as tremors, myoclonus, or dystonic postures may occur.

Autonomic Changes

• The most common are skin color changes (mostly livedo or hyperemia), edema, and increased sweating.

• A temperature difference between the affected and unaffected sides may be seen.

• Other skin changes include increased hair growth, increased or decreased nail growth, and skin atrophy.

• Joint contractures may be seen.

Figure 1. Asymmetric edema and discoloration in the right leg of a patient with CRPS. Used with permission from Weinstock LB, et al. A&A Practice. 2016; 6(9):272-6.

Diagnosis

- The diagnosis of CRPS is primarily based on a thorough history and physical examination.

- The Budapest consensus criteria for the clinical diagnosis of CRPS are as follows.2

- 1. Continuing pain, which is disproportionate to any inciting event

- 2. For the clinical diagnosis of CRPS, the patient must report at least one symptom in three of the following four categories:

- Sensory: Reports of hyperesthesia and/or allodynia

- Vasomotor: Reports of temperature asymmetry and/or skin color changes and/or skin color asymmetry

- Sudomotor/edema: Reports of edema and/or sweating changes and/or sweating asymmetry

- Motor/trophic: Reports of decreased range of motion and/or motor dysfunction (weakness, tremor, dystonia) and/or trophic changes (hair, nail, skin)

- 3. For the clinical diagnosis of CRPS, the patient must display at least one sign at the time of evaluation in two of the four following categories:

- Sensory: Evidence of hyperalgesia (to pinprick) and/or allodynia (to light touch and/or temperature sensation and/or deep somatic pressure and/or joint movement)

- Vasomotor: Evidence of temperature asymmetry (>1°C) and/or skin color changes and/or asymmetry

- Sudomotor/edema: Evidence of edema and/or sweating changes and/or sweating asymmetry

- Motor/trophic: Evidence of decreased range of motion and/or motor dysfunction (weakness, tremor, dystonia) and/or trophic changes (hair, nail, skin)

- 4. There is no other diagnosis that better explains the signs and symptoms.

- There is no gold-standard test for confirming the diagnosis. Nonetheless, certain testing measures have been proven useful.

- Triple-bone scans illustrating increased radiotracer uptake in joints distant from the trauma site.1

- Side-by-side plain radiographs illustrating patchy osteoporosis.1

- Skin temperature measurements show a temperature difference of more than 1°C between the affected and unaffected sides.1

- Increased resting sweat output1

- Testing obtaining abrupt transient relief from pain and dysesthesia with a systemic chemical sympatholysis (i.e., a “Bier block”).1 However, the role of the sympathetic nervous system in the pathogenesis of CRPS remains unclear. Thus, a positive test is no longer considered a diagnostic indicator of CRPS.1 Rather, this response is an important indicator of sympathetically maintained pain.

- Although these tests mentioned above may support the diagnosis of CRPS, they are rarely implemented; the diagnosis of CRPS is largely clinical and one of exclusion.3

Treatment

- A multidisciplinary approach is suggested for the management of CRPS. The goals of therapy include restoring function, reducing pain and disability, and enhancing quality of life while minimizing medication side effects.5

- Treatment is most successful when implemented early in the disease course.5 Table 1 illustrates the different treatment options for CRPS.

Table 1. CRPS treatment options

References

- Salahadin A. Complex regional pain syndrome in adults: Pathogenesis, clinical manifestations, and diagnosis. In: Post T, ed. UpToDate; 2024. Accessed on April 5th, 2025. Link

- Harden RN, Bruehl S, Stanton-Hicks M, et al. Proposed new diagnostic criteria for complex regional pain syndrome. Pain Med. 2007; 8(4): 326-31. PubMed

- Dey S, Guthmiller KB, Varacallo M. Complex regional pain syndrome. In: StatPearls (Internet). Treasure Island, FL. 2025. PubMed

- Taylor S, Noor N, Urtis I, et al. Complex regional pain syndrome: A Comprehensive Review. Pain and Therapy. 2021;10(2): 875–92. PubMed

- Salahadin A. Complex regional pain syndrome in adults: Treatment, prognosis, and prevention. In: Post T, ed. UpToDate; 2024. Accessed on April 5th, 2025. Link

Copyright Information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.