Copy link

Bladder Point-of-Care Ultrasound

Last updated: 12/20/2022

Key Points

- Bladder ultrasound is a quick, easy, and noninvasive way to assess bladder volume, Foley catheter positioning, and evaluate intra-abdominal pathologies.

- Bladder volume can be estimated using the formula: 0.75 x width x length x height.

Clinical Utility

- Bedside bladder ultrasound is commonly used to assess urinary bladder volume, detect correct Foley catheter placement, and evaluate for intraperitoneal free fluid presence.

Technique

- The patient is placed supine with their lower abdomen exposed. The knees may be bent to relax the abdominal musculature if needed.1

- A low-frequency curvilinear probe is preferred to allow for full visualization of the bladder.

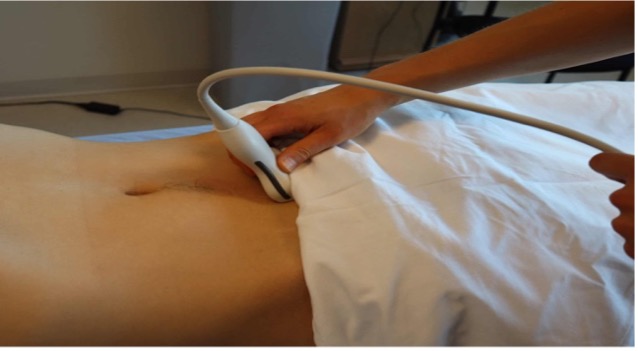

- The probe is placed midline directly above the pubic symphysis in a transverse orientation, with the probe marker pointing towards the patient’s right side (Figure 1). The probe is tilted cranially and/or caudally to find the maximal anterior-to-posterior bladder dimension (Figure 2).2

- The probe is then rotated 90° for imaging of the bladder in the sagittal view (the probe marker should now be pointing cephalad). The probe is tilted and/or translated to visualize the maximal left-to-right bladder dimension (Figure 2).

- The examiner should start with an adequate depth to detect abnormalities in the far field.

Figure 1. Placement of a curvilinear probe in a transverse orientation. Image Courtesy of Vi Dinh, MD, POCUS101.com; reproduced with permission.1

Normal Sonoanatomy

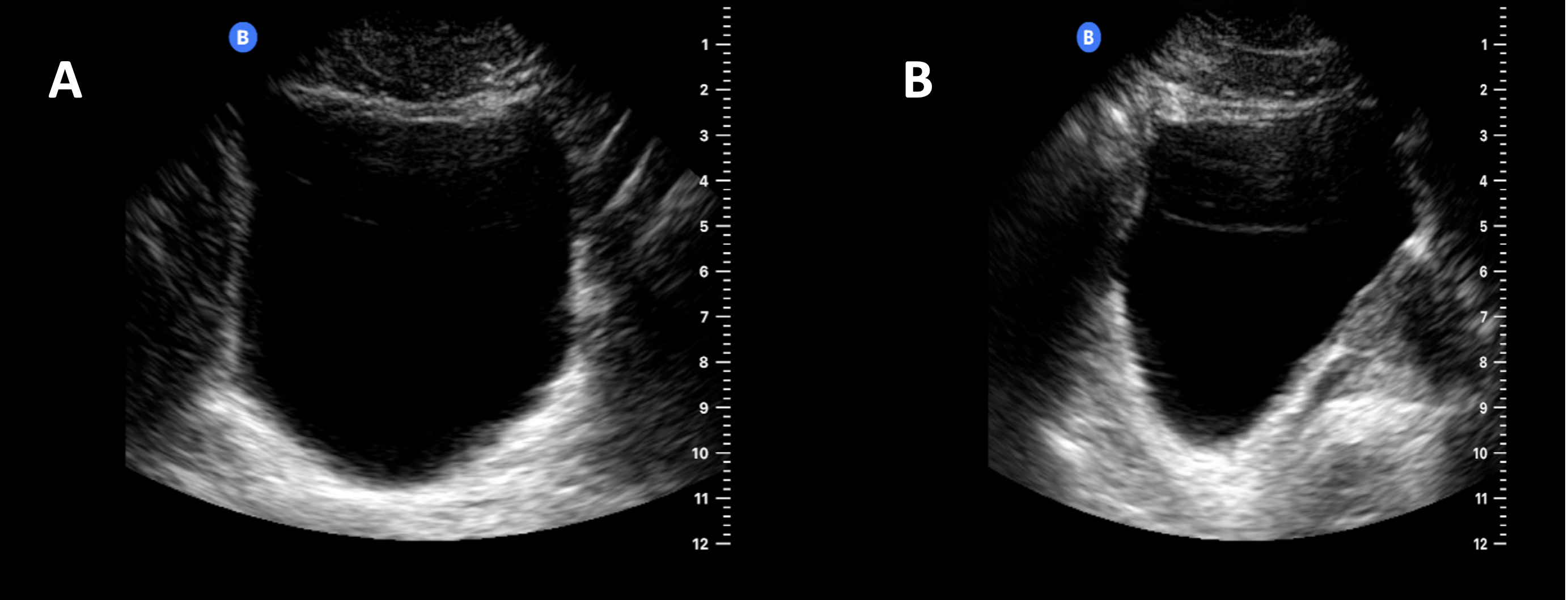

- The bladder appears as a symmetric, smooth, and anechoic (when filled with urine) structure with a wall thickness usually 4cm or less. Although the bladder shape may vary based on the bladder fullness on ultrasound imaging, the bladder is normally seen as a triangular structure on the sagittal view and appears rectangular on the transverse view (Figure 2).

- Posterior to the bladder, the rectum may be visualized. The prostate is identified posterior and caudal to the bladder neck in males. The uterus may be seen posterior and cranial to the bladder in females.3

Figure 2. The bladder appears as an anechoic fluid-filled structure on ultrasound. (A) The bladder is seen as a rectangular structure in the transverse view. (B) In the sagittal view, the bladder appears as a triangular structure.

Pathological Findings

- Bladder ultrasound can identify any of the following: urinary retention, bladder catheter placement, bladder masses, and the presence of free fluid in the pelvis.

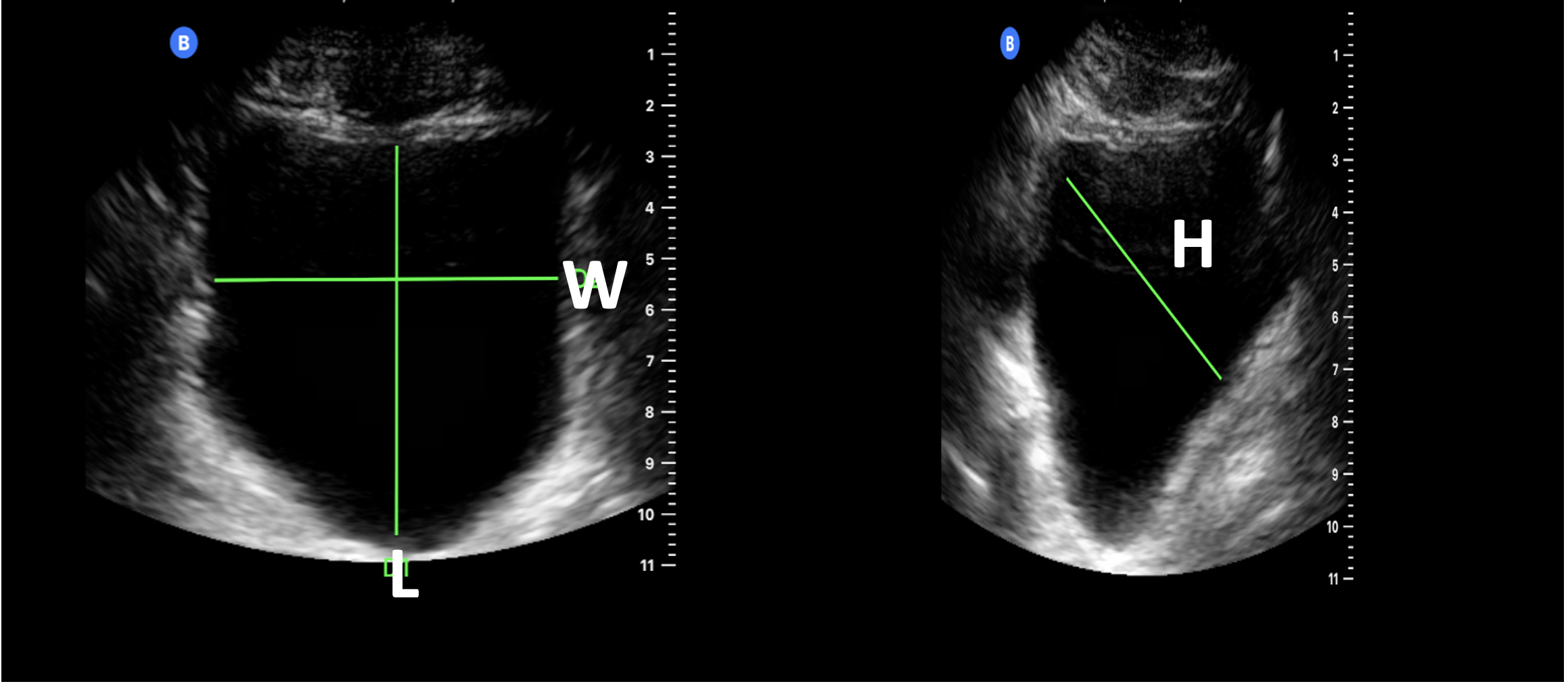

- When assessing for urinary retention, the bladder volumes are measured before and after voiding utilizing the formula 0.75 x width x length x height.4 The length and width are obtained in a transverse view, while the height is measured in the sagittal view (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Bladder volume assessment: The length (L) and width (W) measurements are obtained in the transverse view. The height (H) is calculated in the sagittal view.

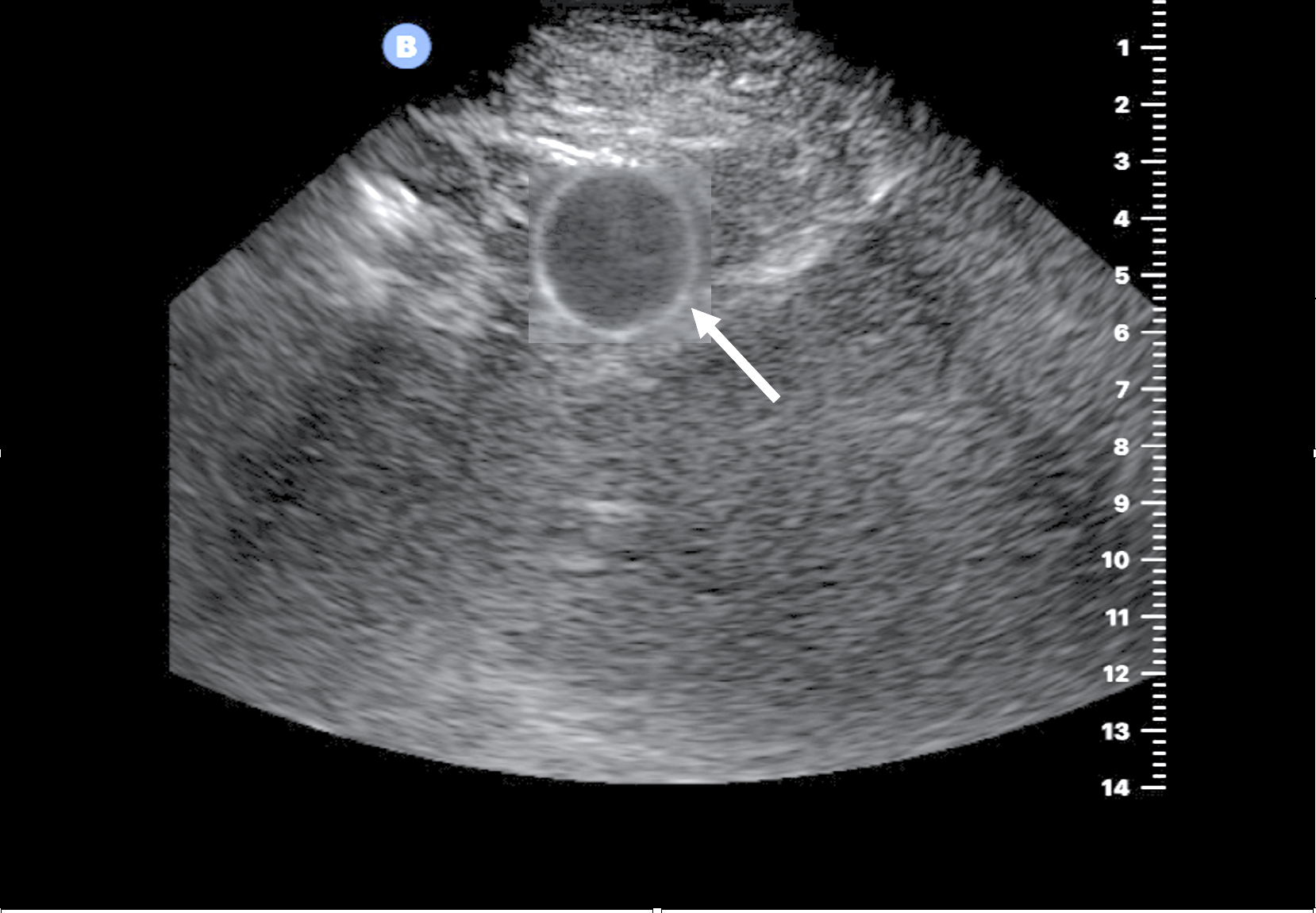

- The placement of a urinary catheter can be confirmed by visualization of a circular hyperechoic ring located within the bladder (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Presence of a correct Foley catheter placement is evidenced by the inflated balloon (arrow) and complete decompression of the bladder.

- While screening for free peritoneal fluid is more comprehensively done with a multiquadrant abdominal ultrasound (e.g., FAST exam), free fluid can nevertheless be seen incidentally while performing bladder ultrasound alone.

- In women, free fluid peritoneal is most likely to be seen between the uterus and rectum (rectouterine pouch of Douglas).

- In men, free fluid is most likely to be seen between the bladder and rectum (rectovesical space).

- Free fluid can also be found lateral or anterior to the bladder in both men and women.

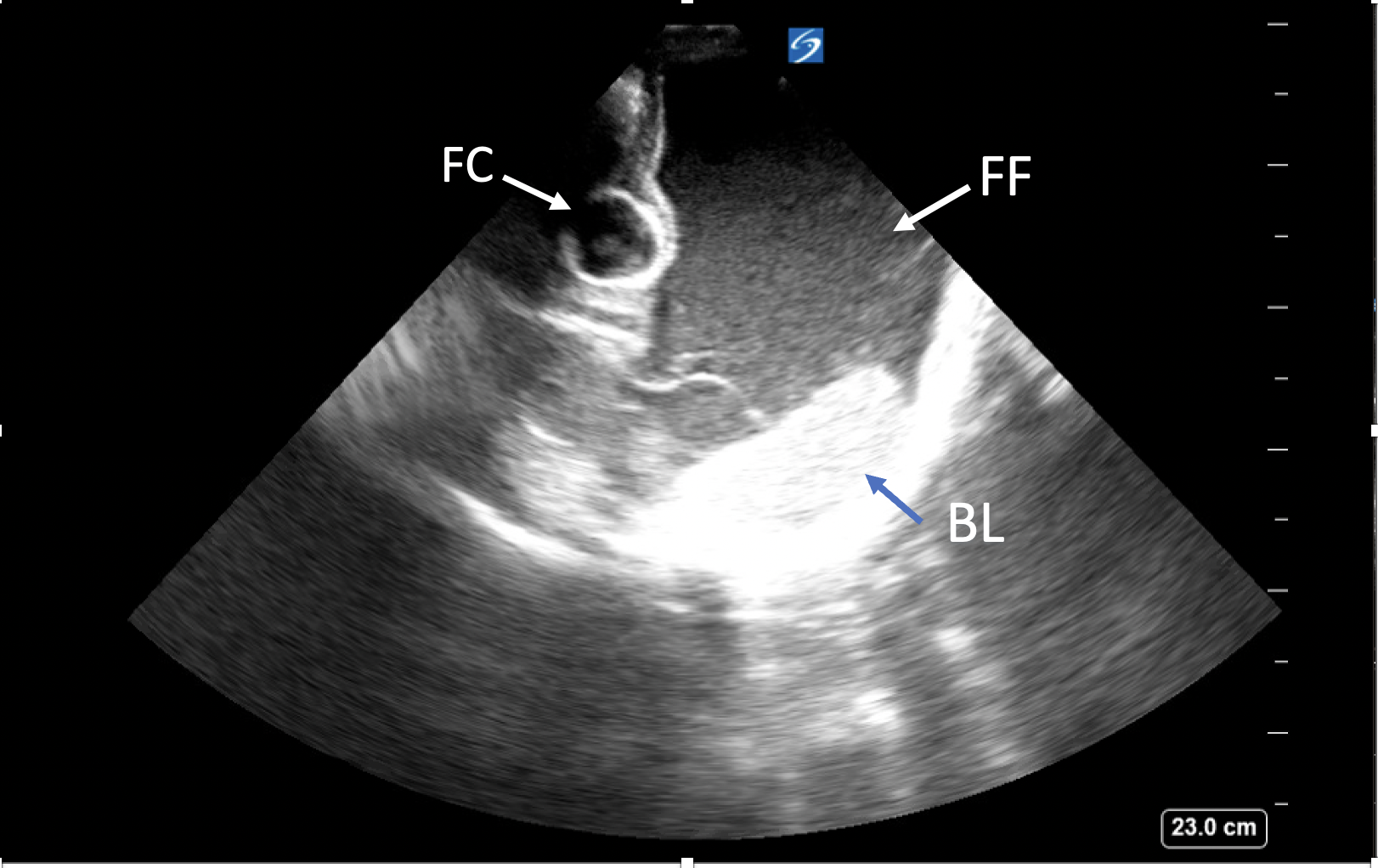

- Large amounts of fluid anterior to the bladder can easily be mistaken for a distended bladder. However, the bladder has well-defined walls, whereas free peritoneal fluid does not. Further, free fluid also sometimes contains floating loops of bowel within it, whereas the urinary bladder does not (Figure 5).4

Figure 5. In this transverse view image, an extensive amount of free fluid (FF) is seen anterior and adjacent to the decompressed bladder with a Foley catheter (FC) in place. Unlike the bladder with well-defined walls, the pelvic free fluid has poorly defined borders and is free flowing. In addition, bowel loops (BL) within the free fluid can also help distinguish it from the bladder. The image was obtained under the cardiac preset. Of note, the probe marker is located on the right of the screen in contrast to the radiology convention used for noncardiac imaging, where the probe indicator will be on the left of the screen.

- Bladder masses are typically irregular echogenic structures that project from the bladder wall or may be found in an area of the bladder with an abnormally thick wall. Most bladder masses are transitional cell carcinoma; however, the differential diagnosis of bladder masses includes bladder diverticula, congenital outpouchings, bladder thickening, and even blood clots.4

Common Pitfalls

- Patients with previous abdominal and/or pelvic surgeries may have scarring that can make imaging the bladder difficult. Significant bowel gas overlying the bladder can also make visualization of the bladder challenging.

- Utilizing ultrasound to estimate bladder volume is superior to standard bladder scanners in patients with ascites since bladder scanners are unable to differentiate the ascites from urine within the bladder. On ultrasound, ascites will show up as hypoechoic or anechoic like urine; therefore, it is important to identify the walls of the bladder, so free fluid in the pelvis is not mistaken for urine in the bladder (Figure 5).4

References

- Dinh V. Bladder Ultrasound Made Easy. Accessed June 10th, 2022. POCUS 101

- Taus PJ, Manivannan S, Dancel R. Bedside Assessment of the Kidneys and Bladder Using Point of Care Ultrasound. POCUS Journal. 2022; 7(Kidney): 94-104. Link

- Sheynkin YR. Ultrasound Evaluation of the Renal System and the Bladder In: Levitov AB, Mayo PH, Slonim AD, eds. Critical Care Ultrasonography, 2e. McGraw-Hill Education; 2015.

- Hassani B. Chapter 26: Bladder. In: Soni NJ, Arntfield R, Kory P, eds. Point of Care Ultrasound. 2nd ed. Elsevier Health Sciences; 2019: 239-245.

Copyright Information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.