Copy link

Beckwith-Weideman Syndrome

Last updated: 05/27/2025

Key Points

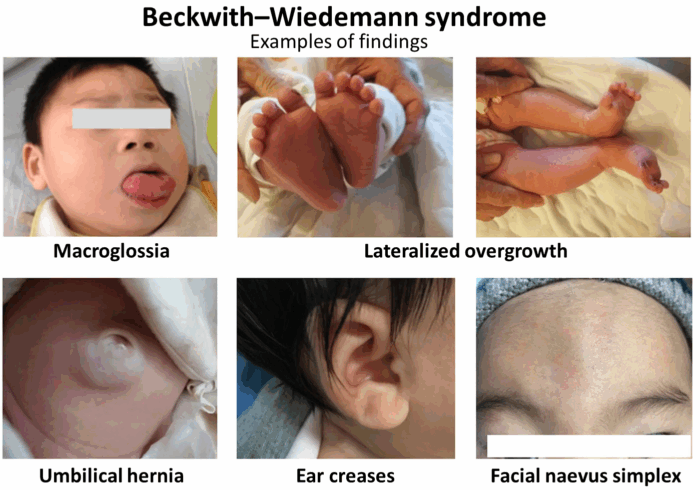

- Beckwith-Wiedemann syndrome (BWS) is the most common congenital overgrowth disorder characterized by macroglossia, macrosomia, visceromegaly, abdominal wall defects, and increased risk of childhood tumors.

- The major anesthetic considerations are potential difficult airway management and perioperative hypoglycemia.

Introduction

- The estimated incidence of BWS is 1 in 10,000 and affects all ethnicities and genders equally. However, this is likely an underestimate due to the mild nature of some clinical features.1

- BWS is likely inherited in an autosomal dominant fashion, but the variation in clinical features is likely explained by a component of incomplete penetrance or other genetic factors.

- It is commonly accepted that BWS is typically caused by dysregulation of the chromosome 11p15.5, leading to tissue overgrowth. However, these genetic changes are usually mosaic in nature, explaining the large array of phenotypes associated with BWS.2 Defects in this chromosomal region can also predict familial risks.

- Other genes linked to tissue overgrowth include the under expression of the p57 gene (KIP2), which encodes a protein that acts as a negative regulator of cell proliferation, and the overexpression of the insulin-like growth factor-2 gene (IGF2).3

Clinical Presentation

- BWS exhibits clinical heterogeneity, but the main features are:

- macroglossia;

- macrosomia (height >97th percentile);

- visceromegaly of intra-abdominal organs;

- abdominal wall defects (omphalocele or umbilical hernia);

- renal abnormalities; and

- earlobe creases or helical pits.3

- Minor findings include polyhydramnios in pregnancy, neonatal hypoglycemia, cardiomegaly/cardiomyopathy, diastasis recti, characteristic facies, nevus flammeus, and advanced bone age.1

Figure 1. Clinical features of BWS. Source: Wikipedia. Wang R, et al. Annotated by Mikael Häggström. CC BY 4.0. Link

- Severity of disease can vary significantly depending on phenotype, with the worst case being pediatric death due to complications from the above features.1

- The incidence of congenital heart disease in BWS is more common compared to the general population; however, most cases are minor defects, such as cardiomegaly, patent ductus arteriosus, patent foramen ovale, or interarterial or interventricular defects, which usually only require echocardiographic monitoring until the defect resolves.2

- Hypoglycemia in infancy occurs in around 30-50% of babies with BWS, which is thought to be related to hyperinsulinemia due to pancreas islet cell hyperplasia.1

- Most reported cases of hypoglycemia are transient and resolve by the first week of life, but up to 20% of episodes can persist.

- Although rare, a pancreatectomy may be necessary in the most severe cases.2

- Tissue hyperplasia leading to macroglossia can cause feeding difficulties, speech impediments, and occasionally obstructive sleep apnea (OSA).1

- It is common for neonates with BWS to gain weight rapidly in the second half of pregnancy and throughout the first few years of life. Height and weight for these individuals in the first few years of life can be in the 97th percentile, whereas head size remains average around the 50th percentile.1

- By the time these individuals reach adulthood, their heights are typically within the normal range. Facial features in BWS also tend to normalize by adolescence.1

- Hemihypertrophy or lateralized overgrowth has also been described in children with BWS, leading to uneven overgrowth of different body parts.2

- Children with BWS tend to develop normally unless they suffered from perinatal complications due to prematurity or uncontrolled hypoglycemia. A duplication in chromosome 11p15.5 also increased the chance of developmental problems.1

- Likely due to predisposition for tissue overgrowth, children with BWS are at an increased risk for embryonal malignancies such as Wilm’s tumor and hepatoblastoma, especially in the first 10 years of life.

- Instances of rhabdomyosarcoma, neuroblastoma, adrenocortical carcinoma, nephroblastoma, and gonadoblastoma have also been described but occur less frequently.3

- The overall risk for developing a tumor in individuals with BWS is estimated to be about 7.5%, but different estimates have been described as high as 21%.1

Anesthetic Considerations

Preoperative Evaluation

- It is essential to perform a thorough airway examination preoperatively, as 90% of children diagnosed with classical BWS exhibit macroglossia, which can commonly lead to upper airway obstruction.2,3

- Preoperative sedation should be avoided or minimized to prevent further airway obstruction.4

- Partial glossectomy is sometimes necessary to help relieve airway obstruction and prevent sleep apnea.3

- Another important but less common consideration in BWS is a smaller-than-expected trachea diameter for a child’s age and size, as well as tracheomalacia.3

- Clinicians should consider ordering sleep studies prior to anesthesia to assess for OSA.

- Blood glucose and electrolytes should be checked preoperatively due to the high incidence of hypoglycemia caused by hyperinsulinemia.

- Due to the increased incidence of congenital cardiac anomalies, a thorough cardiovascular exam and history should be performed prior to anesthesia.

- Intravenous access can be difficult due to neonatal prematurity. Ultrasound-guided vascular access may be necessary.

Intraoperative Considerations

- Macroglossia can make direct laryngoscopy difficult due to visual obstruction of the vocal cords.

- The use of video laryngoscopy or supraglottic airways can be used to overcome concerns with direct visualization.3

- Clinicians should also consider having a tracheostomy kit with a wide range of tracheostomy sizes available as well as informing ear-nose-throat physician (ENT).

- Factors in addition to macroglossia found to be associated with difficult airways include age less than 1 year old, ENT surgeries, history of OSA, low birth weight, and endocrine comorbidities.

- Intraoperatively, ventilation can be worsened due to decreased functional residual capacity (FRC) from visceromegaly.

- Enlarged organs can cause decreased total lung capacity, ultimately worsening FRC.

- FRC is already reduced during general anesthesia, so this, in combination with visceromegaly, can greatly impede ventilation intraoperatively.

- Due to a high incidence of neonatal hypoglycemia, clinicians should consider performing glucose checks intraoperatively.

- Sometimes, perioperative glucose infusions are necessary to maintain normal glucose levels.

- Some children with BWS are on steroids preoperatively and require stress dose steroids prior to surgery to maintain glucose levels.

Postoperative Considerations

- These patients are also at a higher risk of airway obstruction after extubation due to macroglossia and tissue overgrowth.

- It is essential to consider placing the patient in a lateral decubitus position or using an oropharyngeal airway to help mitigate airway obstruction.3

References

- Weksberg R, Shuman C, Beckwith JB. Beckwith–Wiedemann syndrome. Eur J Hum Genet. 2010;18(1):8-14. PubMed

- Brioude F, Kalish JM, Mussa A, et al. Expert consensus document: Clinical and molecular diagnosis, screening and management of Beckwith-Wiedemann syndrome: an international consensus statement. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2018; 14(4):229-49. PubMed

- Baum VC, O’flaherty JE. Beckwith-Wiedemann syndrome. Anesthesia for Genetic, Metabolic, & Dysmorphic Syndromes of Childhood. Wolters Kluwer; 2015.

- Celiker V, Basgul E, Karagoz AH. Anesthesia in Beckwith–Wiedemann syndrome. Paediatr Anesth. 2004;14(9):778-80. PubMed

- Sequera-Ramos L, Duffy KA, Fiadjoe JE, et al. The prevalence of difficult airway in children with Beckwith-Wiedemann syndrome: A retrospective cohort study. Anesth Analg. 2021;133(6):1559-67. PubMed

Copyright Information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.