Copy link

Anesthetic Considerations in the Care of Refugee Children

Last updated: 05/22/2023

Key Points

- Providers serve an ever-increasing number of children from refugee families in the perioperative period.

- The varied experiences and individuality of our patients must be recognized. Refugee children may require surgical procedures that have been delayed due to contextual factors and may present with additional comorbid conditions or higher complexity.

- Prior patient experiences, provider knowledge and expectations, and health care system factors directly impact the clinical encounters of refugee children and their families throughout the perioperative experience.

- Care of refugee children requires a patient-centered approach that focuses on three pillars: trauma-informed care, cultural humility and communication, and coordinated care. This approach meets the needs of refugee children and provides equitable care.

Introduction

- Per recent United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees estimates, 103 million people are forcibly displaced due to conflict, persecution, violence, human rights violations, public disorder, natural disasters, or famine. Of those forcibly displaced, 32.5 million are refugees.1 For forcibly displaced persons, there is an estimated surgical need of 3 million procedures.2

- Nearly half of all forcibly displaced people are children.1 Children are considered amongst the most vulnerable throughout the migration process regarding health risks, physical and mental well-being, and adverse outcomes.3

Refugee Policies

- The United Nations (UN) has been instrumental in advancing the rights of refugees and children. In 1951, the UN defined a refugee as a person who, “owing to a well-founded fear of persecution … is outside the country of nationality and is unable, or owing to such fear, is unwilling to avail oneself of the protection of that country.”4 In 1967, the UN refoulement rights protected refugees against being returned back to a state of harm or danger.4

- With regard to the well-being of children, the 1989 UN Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC) recognized children as individuals with full rights to develop and grow with dignity, such as the right to health, welfare, and education. CRC also emphasized a principle of equity by asserting that the rights of displaced and refugee children are to be held to the same standard as resident populations.5 More recently, the International Society of Social Pediatrics and Child Health (ISSOP) focused on holistic, comprehensive care of the child in the health care setting, ranging from preventive to curative care, and being mindful of linguistic and cultural sensitivity.6

- Providers should recognize the individuality of each patient’s needs. Refugee families have varied experiences. Factors such as whether or not families migrate together, witness trauma, and prior interactions with the health care system must be elicited. Each family has a varying level of literacy and health literacy, and each has a different level of trust for institutions. All these factors should influence how providers approach the care of refugee families.

Key Determinants of Health

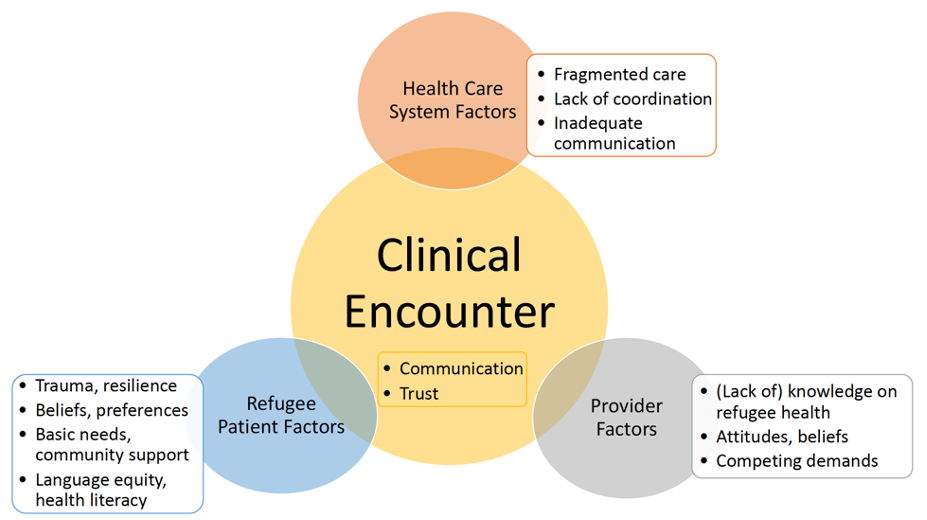

- Providers must focus not only on medical considerations but also incorporate key determinants of health7 into the planning and delivery of anesthetic care. Patient, provider, and health system factors impact access and quality of care received. The perioperative clinical encounter is the intersectionality of these factors. The following key determinants of health should be considered to reduce perioperative care gaps and improve the clinical encounter (Figure 1).8

Figure 1. Key determinants of health. Adapted from Kamath A, et al. Tailoring the perioperative surgical home for children in refugee families. Int Anesthesiol Clin. 2023;61(1):1-7.

Patient-Centered Care Approach

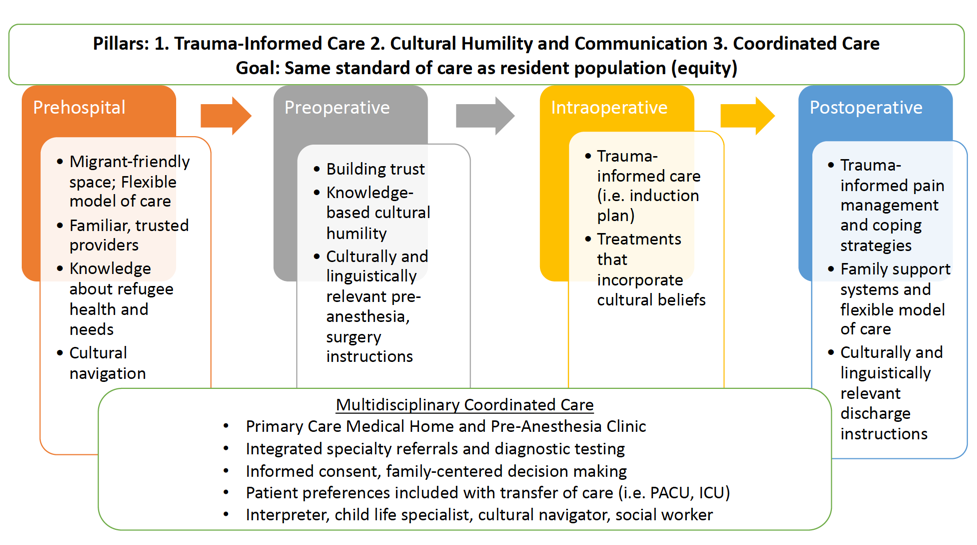

- The Refugee Perioperative Surgical Home (RPSH) care model (Figure 2) has been proposed, 8 which emphasizes a patient-centered care approach and streamlining care across all phases of perioperative care. Integrated care should span not only preoperative, intraoperative, and postoperative phases but, ideally prehospital planning as well.

- Concepts of holistic, individualized care and equity — that is, providing the same standard of care as the resident population — are important. Anesthetic management focuses on three pillars: (1) trauma-informed care (2) cultural humility and communication (3) coordinated care. Regardless of resource constraints, trauma-informed care and cultural humility can be applied to any clinical encounter, and working towards the goal of all care pillars is encouraged.

Figure 2. Refugee Perioperative Surgical Home (PSH) Care Model. Adapted from Kamath A, et al. Tailoring the perioperative surgical home for children in refugee families. Int Anesthesiol Clin. 2023;61(1):1-7.

1. Trauma-Informed Care

- Trauma may occur at any point during a refugee’s migration history and after resettlement. Refugee families have varied experiences with providers, prior anesthetic experiences, and navigating health care systems.

- Trauma-informed care is not a single technique but rather continuous attention, awareness, and sensitivity to create a safe, caring, and inclusive environment. The six CDC guiding principles of trauma-informed care include safety, trust, support, collaboration, empowerment, and cultural issues (Figure 3).9

- For safety and support, providers should be mindful of the separation of the patient and caregiver for induction of anesthesia and recovery. Parental presence, premedication, and child life consultation should be considered as options or in combination for care plan. Patient cues should be noted and acted upon appropriately. Before examining the patient or performing a procedure, the procedure should be explained. The patient should be reunited with their families as soon as possible in the recovery room. Family support systems and flexible models of care should be allowed during the hospital stay.

- For trust and collaboration, providers should aim to build engagement during the preoperative encounter and at every phase of care. This includes allowing time to ask questions, listening carefully, and not rushing clinical discussions. As mentioned, patient cues should be noted and permission sought before acting. Open-ended questions should be used to elicit concerns. Joint decision-making and informed consent should be ensured. The risks, benefits, and when appropriate choices are made, such as for the induction plan, pain management approach, and coping strategies, should be discussed in detail.

- For empowerment, families should be encouraged to speak up and advocate for themselves at any time during the hospital stay and provide information in their preferred language of care (both written and verbal). For example, caregivers should use interpreter services preoperatively, in the recovery room, and throughout the hospital stay. Also, if they have a concern about their child, they should feel comfortable voicing this to the care team at any time.

- For cultural issues, refer to the cultural humility section below.

2. Cultural Humility and Communication

- Cultural humility is not the same as cultural competence. Providers are not expected to know everything and should attempt to “walk in their shoes” as best they can.

- As described above in the trauma-informed care section, beliefs, needs, and concerns should be elicited. Health care providers should treat patients as they would like to be treated, not how they think patients should be treated. Assumptions should be avoided, and instead, patients should be empowered with their voices and their choices when possible. Differences should be respected, and cultural beliefs should be incorporated in treatment and care plans. Providers should be mindful of any potential power imbalances in the patient-provider relationship. All of this is part of communication which are amplified when there are cultural or language nuances.

- Implementation strategies may include:

- Interpreter services and cultural navigators should be proactively requested, and families should be empowered to use these services at any time during their hospital stay.

- Linguistically and culturally sensitive educational materials should be created at every phase, from preoperative visits and phone calls to discharge care instructions.

- Workshops on cultural humility for providers ranging from trainees to hospital employees should be offered.

3. Coordinated Care

- Care should be bundled when possible to improve patient experience, quality of care, and efficiency at every phase of care, starting and returning back to the prehospital phase. For example, hospital appointments and preoperative phone calls in preparation for surgery should be bundled in order to reduce stressors like time off work, transportation issues, and length of hospital stay.

- Providers should collaborate across the health system and during a hospital stay. For example, patient care should be optimized between the preanesthesia clinic and primary care medical home, specialty referrals, and diagnostic workup in the community before arrival. On the day of surgery, providers should work closely with child life consultants, interpreter services, and cultural navigator teams to offer the best care plan possible. While in the hospital, patient preferences or concerns should be relayed to the next provider during signouts and huddles with the ICU, PACU, and inpatient care teams.

References

- UN Refugee Agency. Refugee Data Finder: Key Indicators. Accessed April 28th, 2023. Link

- Zha Y, Stewart B, Lee E, et al. Global estimation of surgical procedures needed for forcibly displaced persons. World J Surg. 2016; 40:2628–34. PubMed

- ISSOP Migration Working Group. ISSOP position statement on migrant child health. Child Care Health Dev. 2018; 44:161–70. PubMed

- UN Refugee Agency. UNHCR Convention and protocol relating to the status of refugees. Accessed April 28th, 2023. Link

- UNICEF. The United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child. Accessed April 28th, 2023. Link

- ISSOP. Budapest Declaration on the Rights, Health and Well-being of Children and Youth on the Move. Accessed April 28th, 2023. Link

- Kilbourne AM, Switzer G, Hyman K, et al. Advancing health disparities research within the health care system: a conceptual framework. Am J Public Health. 2006; 96:2113-21. PubMed

- Kamath A, Gentry K, Dawson-Hahn E, et al. Tailoring the perioperative surgical home for children in refugee families. Int Anesthesiol Clin. 2023;61(1):1-7. PubMed

- CDC Center for Preparedness and Response. 6 guiding principles to trauma-informed approach. Accessed March 31, 2025. Link

Copyright Information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.