Copy link

Anesthesia for Patients with Asthma

Last updated: 09/06/2024

Key Points

- Bronchial asthma is a disease that involves airway inflammation and hyperresponsiveness, specific respiratory symptoms, and obstructive expiratory airflow.

- Symptom frequency indicates the severity of the disease and the level of control. It also affects perioperative risks and guides management.

- Asthma increases the risk of perioperative respiratory adverse events, such as bronchospasm and hypoxemia.

- The highest risk for perioperative respiratory complications occurs during induction, airway manipulation, and emergence.

Introduction

- The Global Initiative for Asthma defines asthma as “a heterogenous disease, usually characterized by chronic airway inflammation and a history of respiratory symptoms, such as wheeze, shortness of breath, chest tightness, and cough, that vary over time and in intensity, together with variable expiratory airflow limitation.”1

- Asthma increases the risk of perioperative respiratory adverse events (bronchospasm, hypoxemia), morbidity, and mortality. This risk increases as asthma severity increases and/or control decreases.

- The physical stimulus of intubation/airway instrumentation is an additional trigger for bronchospasm. Therefore, the highest risk for perioperative respiratory complications occurs during induction, airway manipulation, and emergence.

Preoperative Evaluation

- Preoperative evaluation should include an assessment of severity and control as evidenced by symptom frequency, exercise tolerance/ activity restriction, nighttime awakenings, medication use, hospital admissions, and intubations.2

- Increased symptom frequency such as nocturnal dry cough, more than three wheezing episodes in the last year, a history of eczema, second-hand smoke exposure, prematurity, and wheezing with exercise are associated with an increased risk of perioperative bronchospasm.2,3

- Notes from recent pulmonology consultations and the patient’s adherence to the prescribed plan should be reviewed.

- Chest radiographs have limited use in asthma severity assessment but may be used to rule out comorbid conditions. Pulmonary function tests also have little utility if the patient is stable at baseline.

- For patients with poorly controlled asthma, it is reasonable to postpone elective procedures until better control is reached. For patients with severe asthma that is well-controlled, this may be the optimal time to proceed with the knowledge that they remain at high risk for intraoperative airway events.

- Wheezing, coughing, dyspnea, or chest tightness are common symptoms in an awake patient experiencing bronchospasm preoperatively.

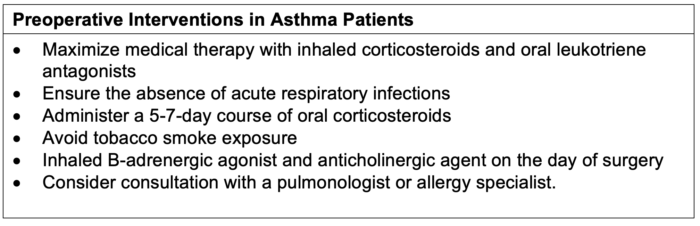

- Preoperative interventions for asthma patients are listed in Table 1.

Table 1. Preoperative interventions in asthma patients. Adapted from Khara B, Tobias JD. Perioperative care of the pediatric patient and an algorithm for the treatment of intraoperative bronchospasm. J Asthma Allergy. 2023; 16:649-60. CC BY NC 3.0

Asthmatic Patients With Upper Respiratory Infections Undergoing General Anesthesia

- Mask ventilation or using a supraglottic airway is a reasonable alternative to tracheal intubation to avoid the stimulation of an endotracheal tube (ETT).

- When tracheal intubation is required, practitioners should establish a deep plane of anesthesia to blunt airway hyperreactivity. Throughout the surgery, maintaining anesthetic depth and adequate analgesia will blunt the stress response to surgical stimulation that may trigger bronchospasm.2

- Deep extubation (assuming no contraindications) is an option to avoid hyperreactivity upon return of airway reflexes, although data have not shown it to be superior.

Perioperative Medications for Asthmatic Patients

- Corticosteroids may have a role in preventing perioperative bronchospasm when given in advance of surgery.4

- Beta-agonists function as direct bronchodilators, and their use before anesthesia may lessen the airway reactivity that occurs following intubation.2,4

- Ketamine is a direct bronchodilator often used in asthmatic patients, but it may also increase airway secretions. Propofol is also a bronchodilator commonly used as an induction agent in asthmatic patients.

- Among the volatile agents, sevoflurane and isoflurane cause bronchodilation. In contrast, desflurane is known to increase airway reactivity and bronchial smooth muscle tone and may precipitate bronchospasm. It is not a preferred agent in asthmatic patients.

- The reversal agent neostigmine increases acetylcholine through the inhibition of acetylcholinesterase. The increased vagal tone may increase the risk of bronchoconstriction and bronchospasm, so use caution when treating asthmatic patients. Sugammadex allows for neuromuscular blockade reversal of select agents without this risk of cholinergic-induced bronchospasm.3

Intraoperative Care

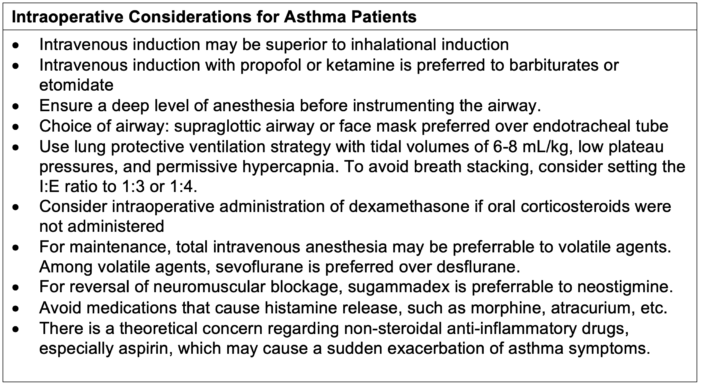

- The primary intraoperative considerations for asthma patients are listed in Table 2.

Table 2. Intraoperative considerations for asthma patients. Adapted from Khara B, Tobias JD. Perioperative care of the pediatric patient and an algorithm for the treatment of intraoperative bronchospasm. J Asthma Allergy. 2023; 16:649-60. CC BY NC 3.0

Emergence from Anesthesia and Postoperative Care

- Bronchospasm may recur or worsen when the patient emerges from anesthesia, and vigilance is recommended.

- There is limited evidence to advocate for awake vs. deep extubation in asthma patients.4

- The key to minimizing postoperative complications is continuous patient monitoring to detect clinical signs of bronchospasm or deterioration in respiratory status, adequate pain control, and ongoing bronchodilator therapies.4

Intraoperative Bronchospasm

- Bronchospasm in an anesthetized and intubated patient presents with increased peak inspiratory pressure and an upsloping EtCO2 waveform indicating obstruction, assuming the ability to ventilate is maintained. Wheezing is often present on auscultation.

- Hypercapnia and hypoxemia may ensue, followed by cardiopulmonary collapse if not treated.

- It is essential to differentiate intraoperative wheezing due to bronchospasm from other causes. A non-exhaustive list of the differential diagnosis includes:

- obstruction of the endotracheal tube (ETT) from a mucus plug;

- kinked ETT or circuit;

- mainstem intubation;

- aspiration;

- pneumothorax;

- pulmonary edema; and

- anaphylaxis often involves systemic signs like angioedema, flushing, urticaria, and cardiovascular collapse.

Treatment of Intraoperative Bronchospasm

- The FiO2 should be increased to maintain oxygen saturation above 90%, and the triggering stimulus should be removed, if possible. The anesthetic should be deepened to facilitate bronchodilation.

- If able to ventilate:

- A beta-agonist, such as albuterol +/- ipratropium, should be administered. Nebulized formulations are preferred due to better controlled delivery within the breathing circuit.

- For ventilated patients, the I:E ratio must be increased to allow for more time in expiration to avoid auto-positive end-expiratory pressure and breath stacking.

- If unable to ventilate:

- Propofol may be administered to deepen the anesthetic depth. Epinephrine may be necessary for severe bronchospasm and impending cardiopulmonary collapse.

- Intravenous (IV) salbutamol is another option for rapid onset bronchodilation (20 mcg/kg IV bolus, then infusion 5-10 mcg/kg/min x1 hour until improvement and then decreased to 1-2 mcg/kg/min until resolution of bronchospasm).2

- Epinephrine 0.05-0.5 mcg/kg/min.2

- Corticosteroids should be administered to reduce inflammation, although their onset of action is not immediate.

- Leukotriene receptor antagonists such as montelukast are used to prevent bronchospasm but have no role in treating acute bronchospasm. The role of methylxanthines is debated and varied.

- Antibiotics are not recommended unless infectious etiologies are present.

- Please see the OA summary on bronchospasm for more details. Link

References

- GINA ©2024. Global Initiative for Asthma, reprinted with permission. Accessed July 3, 2024. Link

- Firth P, Kinane TB. Essentials of pulmonology. In: Cote C, Lerman J, Anderson B. A Practice of Anesthesia for Infants and Children. 6th Edition. Philadelphia, PA; Elsevier; 2019: 281-96.

- Kamassai JD, Aina T, Hauser JM. Asthma anesthesia. In: StatPearls (Internet). Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2023 Jan

- Khara B, Tobias JD. Perioperative care of the pediatric patient and an algorithm for the treatment of intraoperative bronchospasm. J Asthma Allergy. 2023; 16:649-60. PubMed

Copyright Information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.