Copy link

Anesthesia for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy

Last updated: 05/24/2024

Key Points

- Preoperative evaluation and risk assessment are essential to identify and mitigate risks associated with aspiration, hypoxia, and hypoventilation during gastrointestinal (GI) endoscopy.

- Capnography is crucial for patient safety during endoscopy procedures to monitor ventilation and prevent respiratory compromise.

- Anesthesia for endoscopy requires collaboration among gastroenterologists, nursing staff, and anesthesia providers. This ensures optimal patient safety, procedural efficiency, and effective perioperative management of complications.

Preoperative Assessment

- A thorough preoperative evaluation, including medical history and anesthesia-oriented physical examination, is essential. Particular attention should be given to identifying conditions predisposing patients to aspiration, hypoxia, and hypoventilation.

- Close communication with the proceduralist to gain insights into the procedure type, indication, expected duration, potential challenges, and optimal patient positioning is crucial.

- Assessment of Aspiration Risk

- The reported incidence of aspiration pneumonia during or after GI endoscopy is approximately 1.1%.1

- Various factors contribute to aspiration risk1-3, including:

- indeterminate NPO (nil per os) status

- uncontrolled gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD)

- dysphagia

- history of esophagectomy

- gastrointestinal dysmotility or emptying disorders (e.g., gastroparesis)

- achalasia

- esophageal stenosis

- utilization of glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP-1) receptor agonist

- intrinsic or extrinsic gastric or intestinal obstructions (e.g., abdominal compartment syndrome, ascites, advanced pregnancy)

- acute upper GI bleeding

- a history of severe comorbidities such as congestive heart failure, stroke, and insulin-dependent diabetes

- An ultrasonographic assessment of gastric content is recommended in high-risk patients before inducing general anesthesia.6,7

- Gastric content management

- Retained gastric content is frequently encountered during upper endoscopy, with reported rates ranging from 0.3% to 19.0% of cases.8

- In patients at an intermediate risk of aspiration, such as those using GLP-1 receptor agonists, the absence of conclusive evidence from high-quality studies has led to a lack of consensus on best practices.9 Therefore, the choice of anesthesia and airway management remains at the discretion of the clinician.

- However, when opting for sedation without securing the airway in patients at intermediate risk of aspiration, it is crucial to achieve adequate sedation and suppress the gag reflex before inserting the endoscope. In such cases, gastroenterologists can suction fluid contents from the esophagus or stomach via upper endoscopy to reduce potential aspiration risks.

- It is important to highlight that rapid sequence intubation (RSI) should be strongly considered in high-risk patients, as it may decrease the incidence of adverse events without compromising procedural efficacy.1,2

- Assessment of Hypoventilation and Hypoxia Risks4,10

- A standardized airway evaluation is crucial for anticipating and managing airway obstruction, ventilation, and intubation difficulties.

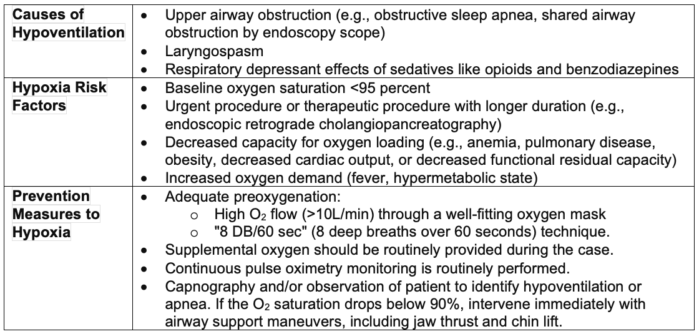

- Upper endoscopy presents a higher iatrogenic risk of hypoventilation and hypoxia, attributed to transient apnea from anesthetic overdose, partial laryngospasm due to suboptimal anesthesia, and the potential for airway obstruction by the endoscopy scope. Table 1 describes the common causes of hypoventilation, risks for hypoxia, and prevention measures.

Table 1. Assessment and prevention of hypoventilation and hypoxia risks

- Exclusion criteria for outpatient endoscopy procedures1-4

- American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) physical status IV or above

- Recent myocardial infarction, stroke, or pulmonary embolism on anticoagulation therapy

- Critical cardiopulmonary comorbidities, including severe aortic stenosis, significant pulmonary hypertension, and severe obstructive or restrictive lung diseases necessitating continuous home oxygen therapy

- Patients with well-compensated ASA III status and those with morbid obesity should undergo prescreening and individualized assessment. Final eligibility for outpatient endoscopy procedures should be determined on a case-by-case basis at the discretion of the preoperative clinic evaluation.

Anesthesia for Endoscopy

- Monitoring:

- Standard ASA monitors, including pulse oximetry, blood pressure, ECG, and capnography, should be universally available in settings where general anesthesia administration is anticipated.

- The integration of capnography during endoscopy markedly diminishes the incidence and duration of apnea, airway obstruction, hypoxia, and hypercarbia.

- Choice of Anesthesia Level1-4

- Determinants include procedure complexity, proceduralist expertise and preferences, patient comorbidities, and the risk of aspiration and airway intervention difficulty.

- Certain patient populations exhibit diminished susceptibility to anesthesia, e.g., patients with anxiety disorders who require home anxiolytics, individuals with chronic pain using opioids, or those engaged in recreational drug use such as marijuana may necessitate higher doses of sedatives and analgesics to achieve optimal drug dosing and administration.

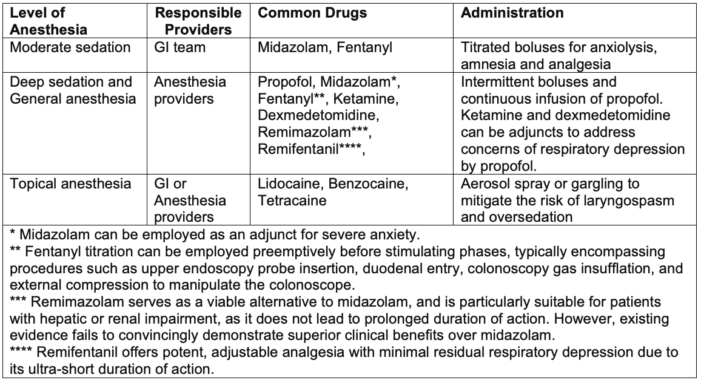

- Table 2 describes the common medications for different levels of anesthesia required for endoscopy.

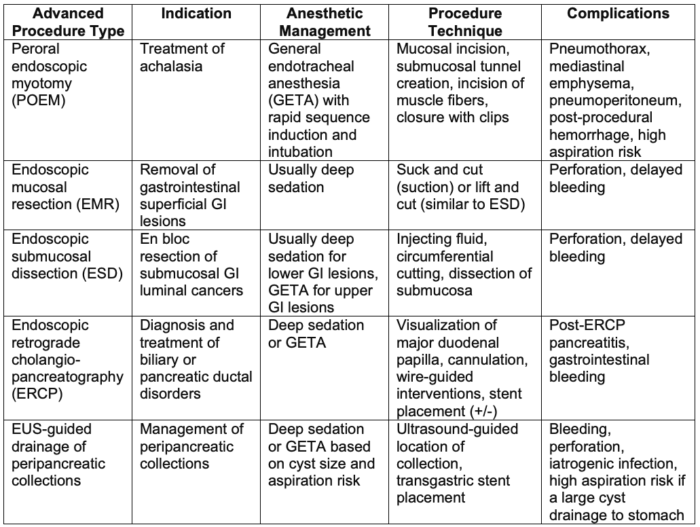

- Advanced endoscopic procedures typically require motionless and well-sedated patients due to their increasing technical complexity and a rising caseload of high-risk patients who are either unsuitable for surgery or are critically ill.4,5 Communication between the anesthesia provider and the endoscopist is necessary to identify and address potential risks proactively. The formulation of an anesthesia plan should involve discussion with the proceduralist and adhere to institutional practices. Common procedures include endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP), peroral endoscopic myotomy (POEM), endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR), endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD), and EUS-guided drainage of peripancreatic collections (Table 3).

Table 2. Level of anesthesia and common drugs for endoscopy procedures

Table 3. Advanced endoscopy procedure and anesthetic management

- Airway Management:

- Oxygen can be delivered via nasal cannula or an oxygen mask during sedation.

- A high-flow nasal cannula may be warranted for patients at higher respiratory risk.

- Preparedness for escalating airway management across sedation stages is critical to mitigate the risk of oversedation. Capnography is essential to monitor the patient’s adequate ventilation and prevent impending hypoxia and cardiopulmonary collapse.

- General anesthesia generally mandates endotracheal intubation or special LMA-Gastro (a dual-channel supraglottic airway device).

- Elective endotracheal intubation1-2: This is recommended for patients anticipated to present with an anatomically challenging airway to avoid uncontrolled scenarios with escalating sedation.

- Workflow1,4:

- Anesthesia professionals often experience time pressure due to high case volumes, short case duration, and rapid case turnover.

- A physician anesthesiologist-led anesthesia care team model optimizes efficiency and patient safety in high-volume, rapid-turnover endoscopy suites.

- Collaborating between anesthesia providers and the endoscopy team in solo practice settings streamlines workflow. For instance, endoscopy staff can facilitate preanesthesia transport and monitor placement, while the anesthesia personnel focus on airway preparation and medication readiness.

- A collaborative team approach and effective communication bolster work efficiency, consensus on anesthetic choice, and patient care quality.

Emergency and Complications in Endoscopy

- Mortality and Major Complications

- Mortality claims in non-operating room settings were double those in operating rooms, with gastroenterology procedures representing the majority of mortality claims3.

- Common major complications include the need for escalation of care, respiratory complications, and significant hemodynamic instability, including cardiac arrest.

- Key contributing factors encompass oversedation, inadequate monitoring, hypoventilation, and hypoxia.

- Airway-Related Adverse Events

- Airway-related adverse events occur five times more frequently in non-operating room cases compared to operating room cases.

- Endoscopy airway management poses logistical challenges due to poor lighting, constrained space, shared or obstructed airway access, patients positioned prone or laterally, and distant locations from additional personnel and equipment.3,4

- Upper endoscopy procedures share the airway, increasing the risk of laryngospasm, particularly in cases of inadequate anesthesia or patients with irritable airways, such as those with a history of smoking or recent upper respiratory infections.4

- During colonoscopy, excessive gas insufflation or external abdominal compression can elevate intraabdominal pressure, heightening the risk of aspiration.4

- Pulmonary Complications

- Inadequate oxygenation/ventilation often stems from oversedation, upper airway obstruction, and respiratory depression induced by sedatives and opioids.3-4

- High-flow nasal oxygenation (HFNO) may enhance oxygenation and reduce hypoxemia risk, albeit potentially predisposing to hypercarbia due to limited capnography utilization.

- Incorporating a capnography sampling port into HFNO devices would enhance patient safety. Capnography and vigilance allow rapid diagnosis of severe hypoventilation.

- Cardiovascular Complications

- Patients with severe comorbidities, ASA physical status ≥3, and oversedation are susceptible to cardiovascular complications,4 e.g., hypotension, cardiac arrhythmias, hypoxemia, myocardial ischemia, and cardiopulmonary arrest.

- Prompt access to inotropes and vasopressors is essential for timely intervention.

- Anesthesia personnel, proceduralists, and support staff must be proficient in defibrillator use and familiar with crash cart locations.

- Proactively considering communication strategies and early calls for assistance are pivotal during critical situations.

References

- Pardo E, Camus M, Verdonk F. Anesthesia for digestive tract endoscopy. Curr Opin Anaesthesiol. 2022;35(4):528-35. PubMed

- Cho YJ. Role of anesthesia in endoscopic operations. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am. 2021;31(4):759-72. PubMed

- Hardman B, Karamchandani K. Management of anesthetic complications outside the operating room. Curr Opin Anaesthesiol. 2023;36(4):435-40. PubMed

- Goudra B. Anesthesia for gastrointestinal endoscopy in adults. In Post T (ed): UpToDate; 2024. Accessed May 05, 2024. Link

- Goudra B, Saumoy M. Anesthesia for advanced endoscopic procedures. Clin Endosc. 2022;55(1):1-7. PubMed

- Eric R. Heinz. Gastric point of care ultrasound. OpenAnesthesia. 2023. Accessed May 06, 2024. Link

- Baettig SJ, Filipovic MG, Hebeisen M, et al. Pre-operative gastric ultrasound in patients at risk of pulmonary aspiration: a prospective observational cohort study. Anaesthesia. 2023;78(11):1327-37. PubMed

- Bi D, Choi C, League J, Camilleri M, et al. Food residue during esophagogastroduodenoscopy is commonly encountered and is not pathognomonic of delayed gastric emptying. Dig Dis Sci. 2021;66(11):3951-9. PubMed

- Hashash JG, Thompson CC, Wang AY. AGA rapid clinical practice update on the management of patients taking GLP-1 receptor agonists prior to endoscopy: Communication. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2024;22(4):705-7. PubMed

- Gonzalez RM. Hypoxia during upper GI endoscopy: There is still room for improvement. APSF Newsletter. 2019 June. Link

Other References

- APSF Podcast. Episode #122 Hyperinflation System Use and Best Anesthetic Practice During Endoscopy Procedures. Link

Copyright Information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.