Copy link

Anesthesia for Cervical Cerclage

Last updated: 10/22/2025

Key Points

- Cervical cerclage placement allows a patient to maintain a pregnancy beyond the second trimester.

- There are several types of cerclages, including transvaginal, transabdominal (TAC), rescue, and prophylactic cerclages.

- Anesthetic objectives for rescue cerclage placement include avoiding increases in intra-abdominal pressure while maintaining patient comfort and fetal perfusion.

Introduction/Indications for Cerclage

Background

- Preterm birth remains the leading cause of perinatal morbidity and mortality in the United States.1,2

- Cervical cerclage is a procedure to reinforce the cervix in the setting of cervical insufficiency.

- Goal: prevention of second-trimester loss or preterm birth due to cervical insufficiency while minimizing preterm birth, preterm premature rupture of membranes (PPROM), and infections.

- Three types: McDonald, Shirodkar, and TAC

- Cervical insufficiency refers to painless cervical dilation resulting in recurrent mid-trimester loss or preterm birth in the absence of contractions or infection.

- Cervical insufficiency is diagnosed clinically and managed per guideline-based risk factors.

- Approximately 1-2% of pregnancies may meet criteria for cerclage, though practice patterns vary.1

- Transvaginal ultrasound is the gold standard for evaluating cervical length and funneling and is performed between 16-24 weeks of pregnancy.

- Physical exam, such as a speculum or digital exam, is used to evaluate for dilation, bulging membranes, and/or signs of infection.

- Symptoms are typically vague, such as a change in vaginal discharge, increased lower abdominal and vaginal pressure, urinary frequency, and back discomfort

Causes of Cervical Insufficiency1,2

- Congenital or developmental causes:

- Mullerian disorders (e.g., unicornate, didelphys, or septate uterus)

- Connective tissue disorders (Ehlers-Danlos syndrome – types I & IV)

- In utero diethylstilbestrol exposure: this is now rare but classically associated with a hypoplastic or T-shaped cervix/uterus.

- Congenital short cervix on imaging (less than 25 mm in the absence of trauma or prior procedures)

- Acquired or Iatrogenic causes:

- Mechanical or surgical trauma to the cervix (e.g., loop electrosurgical excision procedure or cold knife conization, cervical dilation and curettage, cervical laceration)

- Obstetric trauma from second-trimester losses or manual exploration

- Obstetric and reproductive factors:

- History of cervical insufficiency, multiple gestation, polyhydramnios, and infection/inflammation

- Cone biopsy and multiple cervical procedures are leading contemporary risk factors for cervical insufficiency.

- A substantial proportion of cases have no single identifiable cause; instead, they are attributed to a combination of genetic, biomechanical, and inflammatory factors.

Guideline References

- SMFM Consult Series #70 (2024)

- Latest guidance on management of short cervix and indications for cerclage

- ACOG Practice Bulletin #142 (2014)

- Still widely cited, though the guidance is more than 10 years old

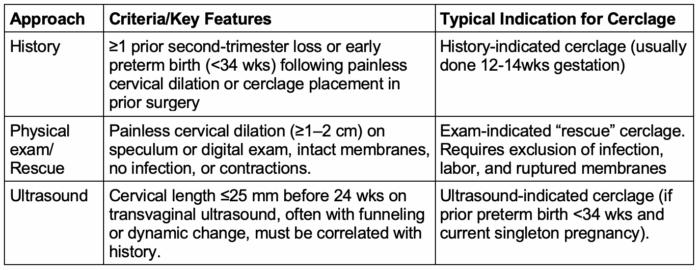

Table 1. Diagnostic approaches for cervical insufficiency1-3

Cerclage Timing

- Assessment of the cervix should be attempted at the 18–22-week anatomy ultrasound using either a transabdominal or transvaginal approach.2

- Cervical cerclage is usually performed between 12 and 24 weeks, depending on the indication.2

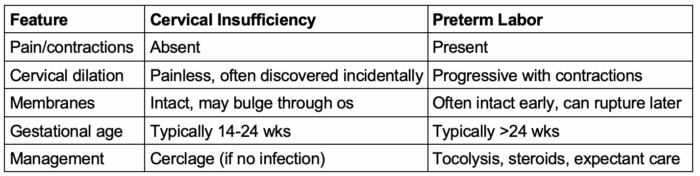

Table 2. Differentiating cervical insufficiency vs preterm labor

Contraindications to Cerclage Placement1,2

- Absolute contraindications: active preterm labor, PPROM, intraamniotic infection, fetal demise or lethal anomaly, active vaginal bleeding, placental abruption, and gestational age ≈24 weeks

- Placing a cerclage in the setting of infection, ruptured membranes, or contractions increases the risk of sepsis, PPROM, and fetal loss.

- Relative contraindications: advanced cervical dilation (>4 cm) with prolapsed or ruptured membranes, multiple gestation (routine prophylactic cerclage not recommended), severe uterine anomaly, extensive cervical resection, or maternal contraindication to anesthesia or surgery.

- Additional practical considerations include active maternal systemic infection, placenta previa or a low-lying placenta, and contraindications to lithotomy or Trendelenburg positioning.

- Even relative contraindications require coordination with the obstetric team to confirm that infection, labor, or ruptured membranes have been excluded before neuraxial or general anesthesia is administered.

Risks of Cerclage Placement3

- Maternal (procedure-related):

- Infection, bleeding, cervical laceration/tearing, uterine irritability/precipitous contractions, rupture of membranes, hemorrhage, preterm labor, and infection

- Fetal/Obstetric:

- PPROM, pregnancy loss, preterm birth despite cerclage, cervical stenosis from cerclage, and need for cesarean (some Shirodkar placements and TAC)

- Risks unique to TAC: visceral injury, hemorrhage, venous thromboembolism (VTE), wound infections, and need for eventual cesarean delivery.

Types of Cervical Cerclage

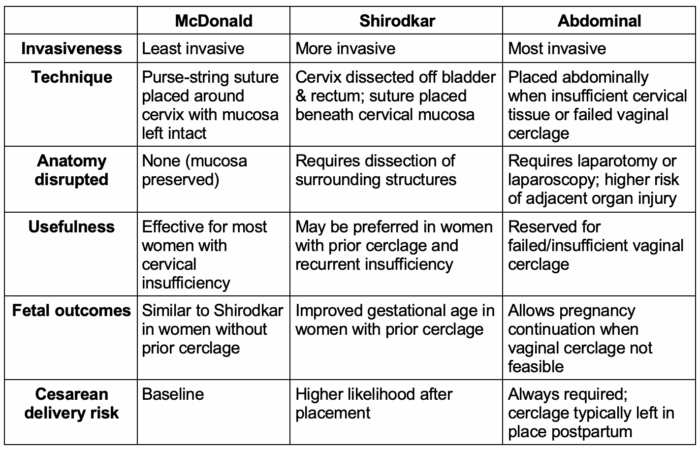

Table 3. Types of cervical cerclage3,4,6

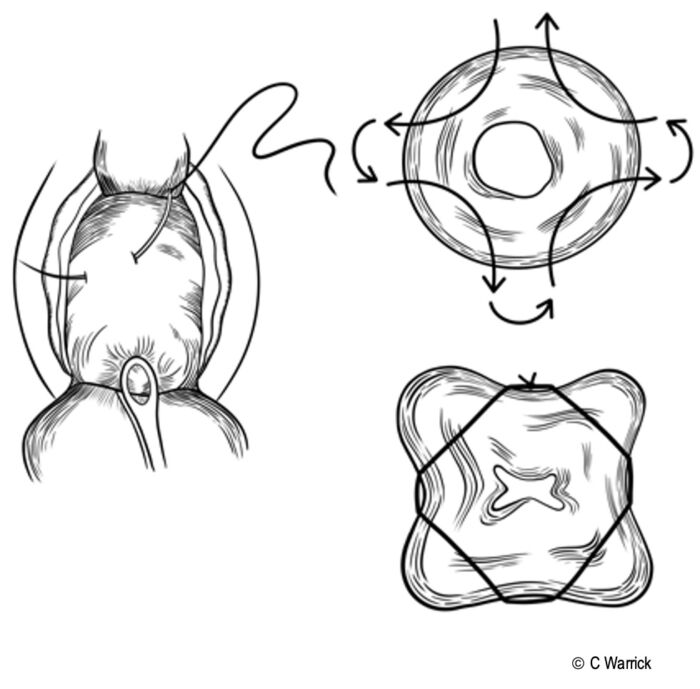

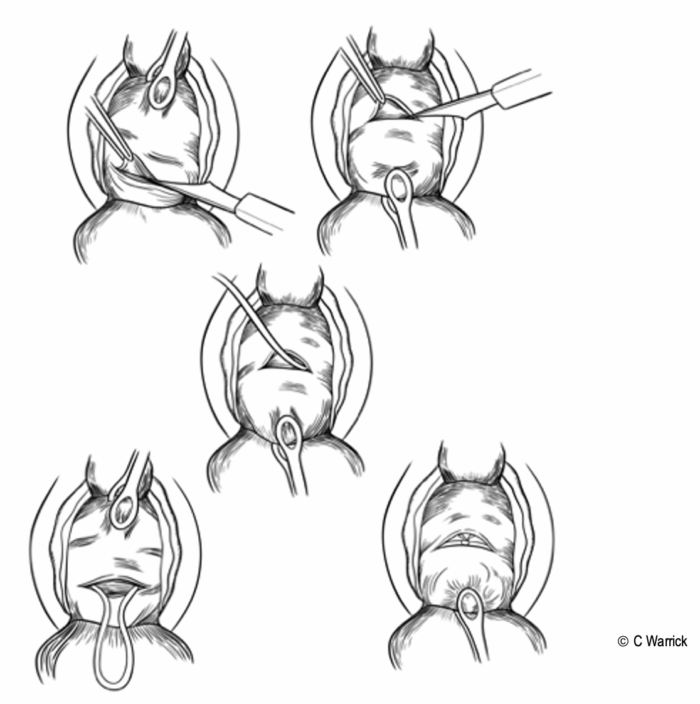

Figure 1. McDonald cerclage. Commissioned by C. Warrick, MD

Figure 2. Shirodkar cerclage. Commissioned by C. Warrick, MD

Procedural Considerations for Cervical Cerclage

Procedural Considerations1,2,4

- Preprocedure evaluation

- Confirm the absence of contraindications

- The optimal procedural window is between 12 and 24 weeks of gestation, depending on the indication for cerclage.

- A fetal assessment should be completed to confirm there has not been a fetal demise or the presence of a fatal anomaly.

- Maternal preparation

- Baseline vital signs, complete blood cell count, Rh status, and vascular access

- Positioning:

- Lithotomy with or without left uterine displacement (dependent on gestational age and other factors)

- Trendelenburg position facilitates amniotic membrane replacement into the uterus.

- This can increase the risk of high neuraxial spread; therefore, the timing of the anesthetic is crucial.

- Membrane management

- If membranes are bulging, Trendelenburg positioning will help the obstetrician gently reduce the membranes. In rare cases, amnioreduction is performed under ultrasound guidance.

- Measures should be considered to reduce increased intra-abdominal pressure (see anesthetic considerations).

- Medications/Adjuncts:

- Nitroglycerin facilitates the replacement of bulging amniotic membranes.5

- Older randomized controlled studies suggested a benefit of antibiotics and indomethacin in exam-indicated cerclage; however, newer meta-analyses found no apparent reduction in preterm birth or perinatal mortality, resulting in institutional practice variations.11

- Cerclage removal usually occurs at 37 weeks’ gestation or earlier following rupture of membranes or onset of labor.

Anesthetic Considerations for Cervical Cerclage

- Anesthetic considerations are addressed in the non-obstetric surgery in pregnancy summary. Link

- Efficacy and outcomes of cerclage placement are similar for neuraxial and general anesthesia with regard to fetal outcomes and risk of preterm labor.7

Preprocedure Preparation

- The absence of contraindications to cerclage and/or regional or general anesthesia should be confirmed.

- Aspiration prophylaxis if indicated (e.g., gastroesophageal reflux disease, diabetes, gastroparesis)8

- A thorough anesthetic preoperative evaluation should be performed, including a physical exam of the heart, lungs, airway, and back.

Gestational Age-Specific Considerations

- More than 13 weeks:

- Increased aspiration risk from decreased lower esophageal sphincter tone (hormonal) and increased intragastric pressure (gravid uterus)9,10

- Aspiration prophylaxis recommended:

- Nonparticulate antacid

- H2 receptor antagonist

- Metoclopramide

- More than 20 weeks’ gestation (earlier in multigestation pregnancies)

- Left-uterine displacement to mitigate hemodynamic disturbances from aortocaval compression

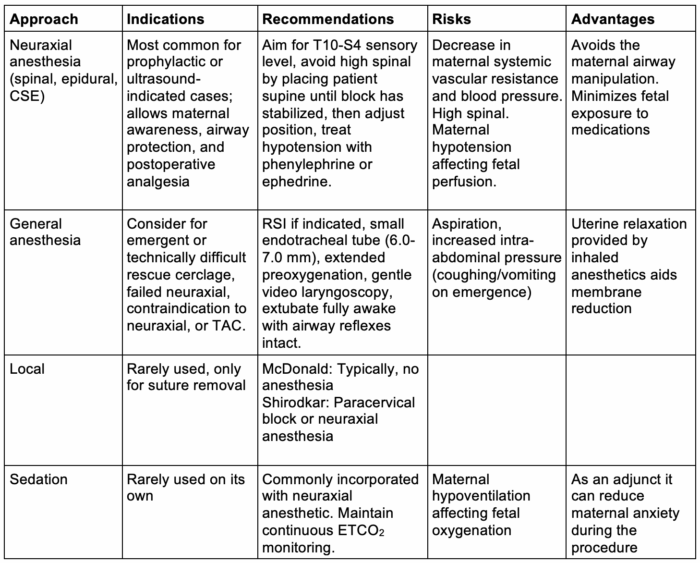

Table 4. Choice of anesthetic technique and general recommendations1,2,6,7

Neuraxial for Cervical Cerclage

- Spinal anesthesia

- Lidocaine: 30-60-minute duration of effect but historically associated with transient neurologic syndrome (TNS)

- Bupivacaine (low dose) has a similar duration and block level without TNS risk.

- Typical dosing: 0.75% bupivacaine (7.5-9 mg) with fentanyl (10-15 mcg) – T10 to S4 block

- Risk: High block if placed in a steep Trendelenburg with a hyperbaric solution

- Chloroprocaine: Faster recovery from motor block with earlier discharge and ambulation.7 Motor block regression for 40 mg intrathecal chloroprocaine occurs around 77 minutes in cesarean delivery patients.7

- Limitation: Short duration, for complicated cerclage placement, consider a combined spinal epidural to extend duration

- Lumbar epidural

- Provides adequate dermatomal coverage from T10 to S4

- Blunts the hemodynamic changes observed with spinal anesthesia

- Typical dosing: 12-15 mL of 2% lidocaine with epinephrine (with/without 50-100 mcg fentanyl)

Anesthesia for TAC

- TAC is usually performed prepregnancy or ≤13 weeks via open, laparoscopic, or robotic approach.

- The anesthetic can be either general anesthesia or neuraxial if an open approach is used. General anesthesia is preferred for laparoscopic and robotic TAC.

- If general anesthesia is utilized during pregnancy, consider low insufflation pressures, left uterine displacement, VTE prophylaxis, ramping, and extended preoxygenation.

- Cesarean delivery is required, and the TAC is usually left in place for future pregnancies.

Postoperative Management of Cerclage

- Fetal assessment via Doppler or nonstress test per gestational age

- Clinician should observe for at least 2 hours for uterine contractions, bleeding, hemodynamic instability, and resolution of neuraxial blockade.

- Most patients have minimal pain. Acetaminophen or a small oral opioid dose can be administered if needed.

- Patients should be monitored for infection, contractions, rupture of membranes, or bleeding during the first 24-48 hours.

- Discharge instructions include return for fever, leakage, bleeding, and/or contractions, and pelvic rest for several days.

Fetal Considerations for Nonobstetric Procedures

See the nonobstetric surgery in pregnancy summary regarding fetal monitoring, medications to avoid during pregnancy, and hemodynamic goals for non-obstetric procedures requiring sedation and/or anesthesia. Link

References

- ACOG Practice Bulletin No.142: Cerclage for the management of cervical insufficiency. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;123(2 Pt 1):372-379 PubMed

- Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine (SMFM); Biggio J; SMFM Publications Committee. SMFM Consult Series #70: Management of short cervix in individuals without a history of spontaneous preterm birth. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2024;231(2):B2-B13. PubMed

- Berghella V, Ludmir J, Simonazzi G, Owen J. Transvaginal cervical cerclage: evidence for perioperative management strategies. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2013;209(3):181-192 PubMed

- Bobotis S, Arsenaki E, Hamilton K, et al. Transabdominal vs transvaginal cervical cerclage in the prevention of preterm birth: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2025:S0002-9378(25)00486-7. PubMed

- Cousins LM, Pue A. Nitroglycerin facilitates therapeutic cerclage placement. J Perinatol 1996;16(2 Pt 1):127-128. PubMed

- Ioscovich A, Popov A, Gimelfarb Y, et al. Anesthetic management of prophylactic cervical cerclage: a retrospective multicenter cohort study. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2015;291(3):509-512. PubMed

- Maes S, Laubach M, Poelaert J. Randomised controlled trial of spinal anaesthesia with bupivacaine or 2-chloroprocaine during caesarean section. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand 2016;60(5):642-649. PubMed

- Wong CA, Loffredi M, Ganchiff JN, et al. Gastric emptying of water in term pregnancy. Anesthesiology. 2002;96(6):1395-400. PubMed

- Delatorre E, Provinciatto H, Rolo LC, Araujo Júnior E. Antibiotics and indomethacin as perioperative management for cerclage: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2025;304:104-108. PubMed

Other References

Copyright Information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.