Copy link

Anesthesia for Abdominal Trauma

Last updated: 01/12/2023

Key Points

- Management of abdominal trauma patients requires early assessment and resuscitation according to Advanced Trauma Life Support (ATLS) principles.

- Knowledge of the trauma mechanism allows the prediction of the severity and pattern of abdominal injury.

- Damage control laparotomy may be required for the unstable patient who cannot tolerate a long definitive repair.

- Angiographic embolization is a minimally invasive option for the treatment of solid organ hemorrhage or direct arterial trauma.

Introduction

- Abdominal trauma is a major cause of morbidity and mortality in all age groups.

- Approximately 75% of blunt abdominal trauma are related to motor vehicle collisions or auto versus pedestrian accidents.1

- Gunshot wounds (GSWs) and stab wounds cause 90% of penetrating abdominal injuries.1

- As members of the multidisciplinary trauma team, anesthesiologists play an active role in the initial assessment and resuscitation of abdominal trauma patients.

Mechanisms of Injury

- Traumatic injuries to the abdomen are either blunt force or penetrating.

- The mechanisms of blunt abdominal trauma include:

- rapid deceleration causing shearing of visceral organs at their points of attachment to the peritoneum;

- compression of solid organs against rigid structures (e.g., posterior thoracic cage or vertebrae column); and

- rapid rise in intraluminal pressure of hollow organs created by outward forces.

- The most commonly injured organs in blunt-force abdominal trauma are the spleen and the liver.1

- Penetrating trauma occurs when a foreign object physically enters through the skin and damages the underlying intrabdominal organs. Penetrating abdominal trauma can be characterized as either:1

- low velocity (e.g., stab wounds) that cause direct laceration, or;

- high velocity (e.g., gunshot wounds) that cause both laceration and cavitation effect by the missile and its fragments.

- The small bowel is the most commonly injured organ in penetrating trauma, followed by the large bowel, liver, and intra-abdominal vasculature.1

Preoperative Evaluation and Management

- The initial assessment, diagnostic evaluation, and management of abdominal trauma patients is based on ATLS principles, which include an assessment of the airway, breathing, circulation, disability, and exposure.2-3

History and Physical Exam

- The trauma history considers the risk for intrabdominal organ damage based on the mechanism of injury.

- Physical exam findings that are associated with intra-abdominal injuries include:

- seatbelt sign or other external signs, such as abrasions, ecchymosis, and contusion patterns;1

- abdominal distention and/or peritoneal signs (e.g., rebound tenderness) indicate intra-abdominal organ perforation or intra-abdominal hemorrhage;

- Cullen’s sign (periumbilical ecchymosis) and Grey-Turner’s sign (flank bruising), which suggest retroperitoneal hemorrhage.

- The absence of abdominal tenderness or pain on the physical exam does not rule out the possibility of intra-abdominal injury.

Diagnostic Tests

- Laboratory studies such as complete blood count, basic chemistry, and coagulation studies can be helpful in identifying patients at risk for injury when used in combination with other clinical findings. Arterial blood gas can be obtained in select cases with hemodynamic instability.1

- Plain radiographs can aid in detecting free air under the diaphragm, finding the location or trajectory of a missile in penetrating trauma, and help in the diagnosis of genitourinary or retroperitoneal hemorrhage.1-2

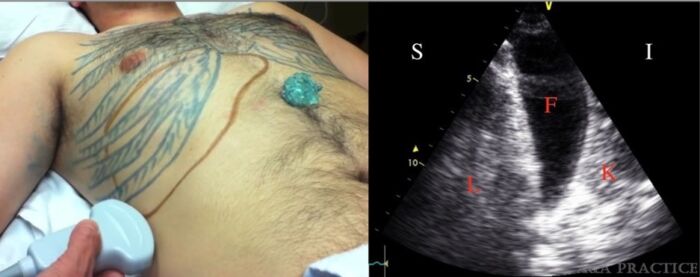

- Focused assessment with sonography for trauma (FAST) is used to detect free fluid in dependent locations within the peritoneal cavity. These include the hepatorenal space (Morison’s pouch), the splenorenal recess, and the inferior portion of the peritoneal cavity (including the pouch of Douglas). The FAST exam should be performed on all hemodynamically unstable blunt abdominal trauma patients as a part of their initial evaluation.1-2

- Diagnostic peritoneal lavage (DPL) has largely been replaced by ultrasonography but can be used in select cases of hypotensive abdominal trauma patients with an equivocal FAST examination.1-2

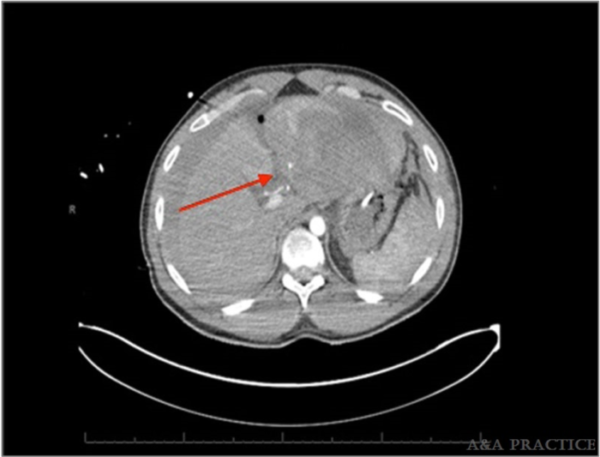

- Abdominal computed tomography (CT) is the test of choice to diagnose specific intra-abdominal organ injuries in hemodynamically stable patients. CT findings that suggest gastrointestinal injury include:1,6

- extravasated intravenous contrast;

- free intra-abdominal fluid;

- extraluminal enteric contrast;

- mesenteric air;

- pneumoperitoneum; and/or

- bowel wall thickening or edema.

Figure 1. Left: suggested position of an ultrasound probe to identify hepatorenal recess (Morison’s pouch). Right: ultrasound image showing fluid in hepatorenal recess (L, liver; F, free fluid; K, kidney). Source: Drew T, et al. Lund University cardiac assist system induced liver laceration and anterior cord infarction after cardiac arrest: A case report. A A Pract. 2020;14(3): 79-82.

Figure 2. Abdominal CT image with red arrow denoting blush from a bleeding artery at the posterior aspect of left hepatic lobe. Source: Drew T, et al. Lund University cardiac assist system induced liver laceration and anterior cord infarction after cardiac arrest: A case report. A A Pract. 2020;14(3): 79-82.

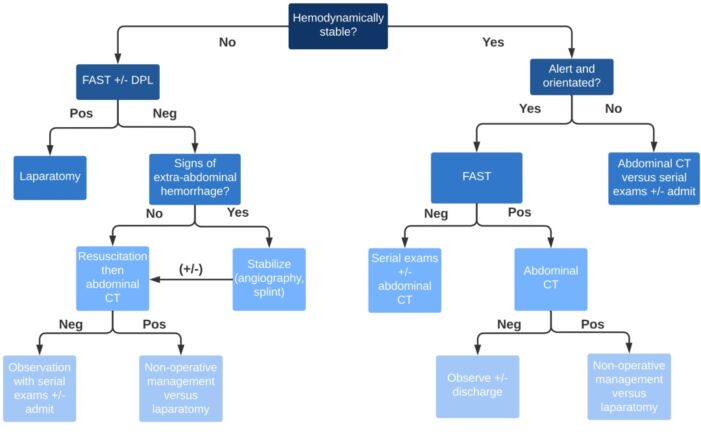

Management of Blunt Abdominal Trauma Patients

Hemodynamically Unstable Patients

- Unstable patients with suspected traumatic gastrointestinal injury on initial presentation should undergo an abdominal exploration.1-2

- Hypotension and tachycardia in the absence of a large scalp laceration or extremity trauma that does not improve with initial fluid resuscitation should be attributed to active abdominal or retroperitoneal bleeding.

- All hemodynamically unstable blunt abdominal trauma patients require a FAST exam. A positive FAST exam in an unstable blunt abdominal trauma patient warrants an emergent laparotomy.

- Other absolute indications for operative intervention include diffuse abdominal pain with peritonitis, and initial imaging studies demonstrating gastrointestinal perforation.2-4

- Patients with a limited or negative FAST exam and positive extra-abdominal signs of hemorrhage should be stabilized with angiography, resuscitative endovascular balloon occlusion of the aorta (REBOA), or splint.2

- Abdominal CT is reserved for unstable blunt abdominal trauma patients who can be resuscitated adequately and can undergo scanning.2

- Clinicians must search for alternative sources of hemorrhage or nonhemorrhagic causes of shock in unstable blunt abdominal trauma patients with negative diagnostic tests.

Hemodynamically Stable Patients

- Management of hemodynamically stable blunt abdominal trauma patients depends on an assessment of their risk factors for intra-abdominal injury.

- For patients deemed low risk by presentation, a period of observation that includes serial vital signs, abdominal examinations, and the FAST exam is sufficient to identify intra-abdominal injury.1,2

- For patients at high risk for abdominal trauma by presentation, an abdominal CT scan is the preferred modality to identify intra-abdominal injury.

Figure 3. Algorithm for the management of patients with blunt abdominal trauma based on hemodynamic stability.

Anesthetic Considerations in Exploratory Laparotomy

General considerations2,3

- Rapid sequence induction (RSI) and intubation are recommended, given the high risk for aspiration.

- Two large-bore peripheral intravenous (IV) lines are preferred in veins that drain into the superior vena cava as the inferior vena cava could be disrupted by the injury.

- Intraosseous lines can be used as an alternative in patients with difficult IV access.

- Early activation of massive transfusion protocols and mobilizing the availability of blood products is imperative in patients that require blood transfusions.

- Hematocrit, ionized calcium, and coagulation studies should be used to guide the transfusion of blood products.

- Parameters such as pulse pressure variation, stroke volume variation, base deficit, and lactate levels can also be used to guide resuscitation.

- Normothermia should be maintained with the use of warmed IV fluids and blood products, forced-air warming blankets, and a gel or fluid warming pad under the patient.

Induction Agents3

- In hypovolemic patients, a smaller total blood volume results in higher serum levels of anesthetic agents.

- Agents that act as direct myocardial depressants and vasodilation should be avoided.

- Preferred induction agents for patients in hypovolemic shock include etomidate (0.1-0.2 mg/kg) and ketamine (0.25-1 mg/kg).

Neuromuscular Agents3

- Succinylcholine (1-1.5 mg/kg) is commonly used for RSI, given its fast onset (30-60 seconds). Importantly, succinylcholine is contraindicated in patients with spinal cord injury or burn injury 48 hours after the insult, given the risk for hyperkalemia.

- Rocuronium (1-1.2 mg/kg) can also be used for RSI. There is a slight delay in the onset of action (60-90 seconds) compared to succinylcholine.

Maintenance of Anesthesia

- The minimum alveolar concentration can be reduced in hypoxemia, severe anemia, and hypotension.

- Volatile agents can cause direct myocardial depression. Thus, lower concentrations should be used and titrated to the patient’s blood pressure.

- Nitrous oxide should be avoided because it can diffuse into air-filled cavities and can cause bowel distention.

- Total IV anesthesia with propofol may be used.

- Neuraxial and regional anesthesia is not recommended because its sympathectomy effect can cause severe hypotension and/or cardiac arrest in hypovolemic patients.

Damage Control Surgery and Resuscitation

- Damage control laparotomy is reserved for unstable patients that require an operative intervention to treat life-threatening conditions but do not have the physiologic reserve to tolerate a prolonged operation.4,5

- The indications for damage control surgery include:

- patients in extremis;

- patients that require large-volume resuscitation; and

- patients with severe degree of physiologic insult, including hypothermia, coagulopathy, and/or evidence of persistent cellular shock.

Phases of Care5

- Phase 0 includes rapid transport and triage for treatment. Only interventions that are necessary to control hemorrhage and promote gas exchange are performed.

- Phase 1 consists of the initial operation to control hemorrhage with a focus on limiting contamination from perforated gastrointestinal organs and to maintain perfusion to vital organs. Phase 1 results in temporary abdominal closure.

- Phase 2 involves damage control resuscitation in the intensive care unit:

- aggressive IV fluid therapy to achieve euvolemia;

- maintenance of systolic blood pressure greater than 80-90 mmHg until major bleeding has been controlled in patients without head trauma;

- replenishment of blood composition for target hemoglobin 7-9 g/dL and correction of coagulopathy with cryoprecipitate, fibrinogen, and prothrombin complex concentrate;

- restoration of end-organ perfusion as indicated by pH greater than 7.25, arterial carbon dioxide less than 50 mmHg, and decreasing lactate levels; and

- preservation of normothermia with warmed IV fluids, convective warming blankets, forced air warming, and gel or fluid warming pads.

- Phase 3 involves definitive repair of injuries temporized during damage control surgery. Timing is dependent on the patient’s physiologic status, but phase 3 is typically 24-40 hours following the initial injury.

- Phase 4 consists of delayed soft-tissue reconstruction after complete recovery from injuries. Phase 4 is only required when primary fascial closure of the abdominal wall or definitive soft tissue coverage cannot be performed during the definitive repair.

Role for Angiographic Embolization

- Angiographic management of abdominal trauma uses minimally invasive approach for the nonoperative management of solid organ hemorrhage or direct arterial trauma.

- Embolic agents such as gel foam, coils, particulates, and n-butyl cyanoacrylate glue are delivered through blood vessels to achieve hemostasis.6

- Use of angiographic embolization can avoid open abdominal exploration and preserves the tamponade effect from potential hematomas.

- Common angiographic treatments include embolization of the splenic artery, hepatic vasculature, and bleeding pelvic vessels.6

- The use of angiography depends on several factors, including the patient’s clinical scenario, hemodynamic stability, and the need for resuscitation. Thus, the order and timing of angiographic embolization versus laparotomy remain a matter of debate.

References

- Isenhour JL, Marx J. Advances in abdominal trauma. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 2007;25(3):713-33. PubMed

- Brenner M, Hicks C. Major abdominal trauma: Critical Decisions and New Frontiers in Management. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 2018;36(1):149-60. PubMed

- Tobin J, Grabinsky A, McCunn M, et al. A checklist for trauma and emergency anesthesia. Anesth Analg. 2013. 117(5):1178-84. PubMed

- Tobin J, Varon, A. Update in trauma anesthesiology. Anesth Analg. 2012;115(6):1326-33. PubMed

- Johnson JW, Gracias VH, Schwab CW, et al. Evolution in damage control for exsanguinating penetrating abdominal injury. J Trauma. 2001;51(2):261-71. PubMed

- Ptohis ND, Charalampopoulos G, Abou Ali AN, et al. Contemporary role of embolization of solid organ and pelvic injuries in polytrauma patients. Front Surg. 2017;4(43):1-6. PubMed

Other References

- Varon A and Smith C. 2017. Essentials of trauma anesthesia. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, pp.232-45.

- Diercks D and Clarke S. 2020. Initial evaluation and management of blunt abdominal trauma in adults. In Moreira, M. and Khurana, B (Eds.), UpToDate. Link

Copyright Information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.