Copy link

Acute Respiratory Failure in Pregnancy: ICU Management and Anesthetic Considerations

Last updated: 07/30/2025

Key Points

- Optimal management of respiratory failure in pregnant patients requires consideration of gestational age, fetal status, and pregnancy physiology and is best provided by a multidisciplinary team.

- Pregnancy is not a contraindication to the use of rescue therapies for acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), including prone positioning, inhaled vasodilators, and extracorporeal life support when indicated.

Ventilation Management

Noninvasive Ventilation (NIV)

- High-flow nasal cannula (HFNC) involves administering 100% humidified and heated oxygen at a flow rate of up to 60 L/min. HFNC may reduce the risk of invasive mechanical ventilation in patients with hypoxemic respiratory failure and is considered safe and reasonable to trial in pregnant patients.1

- The use of NIV with bilevel positive airway pressure and continuous positive airway pressure is controversial in ARDS, as it has not been shown to reduce the incidence of intubation and mechanical ventilation. Furthermore, the physiologic changes of pregnancy that predispose parturients to aspiration make NIV a less attractive option.

- Failure to clinically improve with HFNC or NIV should be identified promptly, and intubation with mechanical ventilation should be pursued.

Intubation and Mechanical Ventilation

- Hormonal changes in pregnancy lead to increased tissue friability and airway edema, predisposing to difficult intubation.

- Physiological changes in pregnancy include increased tidal volume, decreased functional residual capacity, decreased total respiratory compliance, increased minute ventilation, and increased oxygen consumption, which predisposes these patients to rapid desaturation in the setting of apnea.2

- Pregnant patients with ARDS should be managed on the ventilator with settings consistent with ARDS Network ventilation with low tidal volumes of 6-8 mL/kg predicted body weight and goal plateau pressures of ≤ 30 cm of water.3

- The physiologic changes in pregnancy result in a higher PaO2 (90-100 mmHg) and lower PaCO2 (28-32 mmHg). A goal PaO2 ≥ 70 mmHg and saturation ≥ 95% is recommended to avoid fetal distress secondary to hypoxia. A goal of PaCO2 ≤ 40 mmHg is generally recommended to avoid fetal hypercarbia.

- Sedation and analgesia should be administered to pregnant women who are intubated and mechanically ventilated for comfort and ventilatory synchrony. Propofol, opioids, benzodiazepines, and dexmedetomidine may all be appropriate.

Refractory Hypoxemia

Neuromuscular Blockade

- Early initiation of neuromuscular blockade for refractory ARDS may decrease mortality.

- There are no contraindications to neuromuscular blockade during pregnancy as a rescue therapy for refractory ARDS, and the use of this strategy has been extensively described in pregnant patients.4

Prone Positioning

- Prone positioning in mechanically ventilated patients with severe ARDS decreases mortality, with benefits most pronounced with longer durations (>12 hours/day).5

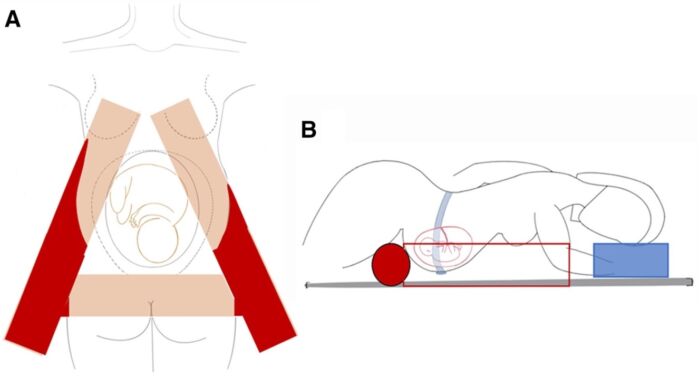

- Prone positioning is feasible in pregnant patients but requires attention to positioning and padding to prevent aortocaval compression, offload the uterus, and allow access to fetal monitoring.

Figure 1: Cushioning for prone positioning during pregnancy with the “A frame.” (A) Aerial view of the patient, resting on an “A” frame configuration of cushions. The pelvis and upper body are supported by 2 limbs of the “A,” and the pelvis is supported by a horizontal cushion. The abdomen is free in the hollow of the “A” frame, and there is space to insert a fetal heart rate monitor and a tocodynamometer. B, Lateral view of patient on the “A” frame. The head is turned to 1 side, with ipsilateral arm in swimmers’ position. Cushions support the lower extremities to facilitate cannula flow by avoiding excessive hip flexion. Used with permission. Wong MJ, et al. Anesth Analg. 2022.6

Pulmonary Vasodilators

- Pulmonary vasodilators are well tolerated and may be beneficial in pregnant patients with severe ARDS.

- Inhaled vasodilators including nitric oxide (iNO) and inhaled prostaglandins have been shown to improve the PaO2 in patients with severe ARDS; however, this benefit has not translated to improvement in mortality or days on mechanical ventilation.7

- Inhaled epoprostenol has been shown to have comparable clinical efficacy to iNO for improvement in oxygenation and ventilation in patients with severe ARDS and no difference in clinical outcomes including length of stay, duration of mechanical ventilation, and mortality at a lower cost.8,9

Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation (ECMO)

- In cases of severe, refractory ARDS, venovenous ECMO may be utilized as a rescue therapy.

- The most recent systematic reviews examining the use of ECMO in pregnancy for ARDS show superior survival rates (nearly 80%) compared to the general population for respiratory indications (58%).10-12

- Neonatal complications are higher in pregnancies where the mother undergoes ECMO during pregnancy, including preterm delivery, intensive care unit admission, and mortality. Delivery of the fetus prior to initiation of ECMO is not a requirement and is only initiated if needed for maternal and/or fetal indications.

Delivery Considerations

Fetal Monitoring

- Maternal condition is often reflected in the fetal status, and fetal heart rate monitoring is routinely performed in critically ill obstetrical patients.

- Intermittent (daily or multiple times during the day) or continuous fetal heart monitoring may be utilized, depending on the patient’s acuity, with an individualized approach based on multidisciplinary input.

- There is no expert consensus for guiding the frequency of checks, and the decision should be made case-by-case based on input from interdisciplinary teams, neonatal resuscitative resources, and patient preferences.

Timing of Delivery

- Equipment for emergency delivery and neonatal resuscitation should be available at the bedside of any pregnant patient in the intensive care unit.

- The decision to proceed with delivery of the fetus is complex and case-specific; multidisciplinary teams including maternal fetal medicine, critical care, obstetric anesthesiology, and neonatology should weigh the relative risk-benefit for each case with consideration of gestational age, underlying illness, and maternal status.

- Prolonging the pregnancy to allow fetal growth in utero (ideally beyond 32 weeks gestation) is generally the goal.

Method of Delivery

- Most women with severe ARDS are delivered via cesarean section.

- Fluid intake should be restricted as much as possible while maintaining adequate oxygenation and blood pressure.

- An individualized plan for delivery should be made based on the gestational age, patient status, etiology of respiratory failure, need for advanced therapies, and clinical stability.

Anesthetic Considerations

- Neuraxial analgesia and anesthesia are associated with decreased morbidity in pregnant patients and reduced fetal exposure to systemic medications, as well as superior pain control and reduced oxygen consumption.

- The decision to proceed with neuraxial analgesia or anesthesia in patients with acute lung disease is individual and should take into consideration additional conditions and therapy, fluid status, and presence of infection.

- In obstetrical patients who are already intubated and mechanically ventilated, there is no data as to the added benefit of a neuraxial procedure for cesarean delivery, and they are more likely to receive general anesthesia.

- Women who are on anticoagulation for any reason, including mechanical circulatory support, require a plan for cessation timing and monitoring if neuraxial anesthesia is pursued, given the risk of epidural hematoma.

References

- Watts A, Duarte AG. Acute respiratory distress syndrome in pregnancy: Updates in principles and practice. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2023;66(1): 208-22. PubMed

- Lapinsky SE. Acute respiratory failure in pregnancy. Obstet Med. 2015:8(1): 126-32. PubMed

- Walkey AJ, Goligher EC, Del Sorbo L, et al. Low tidal volume versus non-volume-limited strategies for patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome. A systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2017; 14(supplement_4): s271-s279. PubMed

- Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine management considerations for pregnant patients with COVID-19. 2021. Link

- Munshi L, Del Sorbo L, Adhikarni NKJ, et al. Prone position for acute respiratory distress syndrome. A systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2017; 14(Supplement_4): S280-S288. PubMed

- Wong MJ, Bharadwaj S, Galey JL, et al. Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation for patients with ARDS: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Anesth Analg. 2022:135(2):277-289. PubMed

- Fuller BM, Mohr NM, Skrupky L, et al. The use of inhaled prostaglandins in patients with ARDS: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Chest. 2015;147(6): 1510-22. PubMed

- Buckley MS, Agarwal SK, Garcia-Orr R, et al. Comparison of fixed dose inhaled epoprostenol and inhaled nitric oxide for acute respiratory distress syndrome in critically ill adults. J Intensive Care Med. 2021: 36(4): 466-76. PubMed

- Valsecchi C, Winterton D, Safaee Fakhr B, et al. High-dose inhaled nitric oxide for the treatment of spontaneously breathing pregnant patients with severe COVID-19 pneumonia. Obstet Gynecol. 2022:140(2): 195-203. PubMed

- Naoum EE, Chalupka A, Haft J, et al. Extracorporeal life support in pregnancy: A systematic review. J Am Heart Assoc. 2022;9(13): e016072. PubMed

Other References

- Naoum E. OpenAnesthesia. OA-SOAP Fellow Webinar Series. Extracorporeal Life Support in Pregnancy. Published: October 1, 2021. Accessed: July 30, 2025. Link

Copyright Information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.