Copy link

Acute Kidney Injury

Last updated: 05/27/2025

Key Points

- Acute kidney injury (AKI) is a clinical syndrome that is characterized by a rapid decline in glomerular filtration rate (GFR) with resultant accumulation of metabolic waste products.

- The incidence of AKI is about 5-7% in hospitalized patients and greater than 50% in critically ill patients.

- AKI is associated with an increased risk of cardiovascular events, progression to chronic kidney disease (CKD), long-term morbidity, and mortality.

- Causes of AKI fall into three groups: prerenal, intrinsic renal, and postrenal AKI.

- General management includes volume optimization, vasopressor support, avoidance of nephrotoxic agents, renal replacement therapy, if needed, and follow-up.

Definition

- AKI is characterized by a sudden decrease in renal function. It can be associated with a rapid increase in serum creatinine, a decrease in urine output, or both.1

- The Kidney Disease Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) definition is widely utilized to diagnose AKI. An increase in serum creatinine of ≥ 0.3mg/dL within 48 hours, or creatinine ≥1.5 times baseline in 7 days, or urine output of < 0.5 mL/kg/h for 6 hours indicates the presence of AKI.1

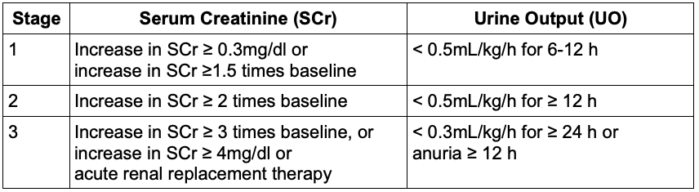

- In addition, based on the rise in serum creatinine and reduction in urine output, AKI could be categorized as stage 1, 2, or 3 (Table 1).

Table 1. Kidney Disease Improving Global Outcomes staging of acute kidney injury

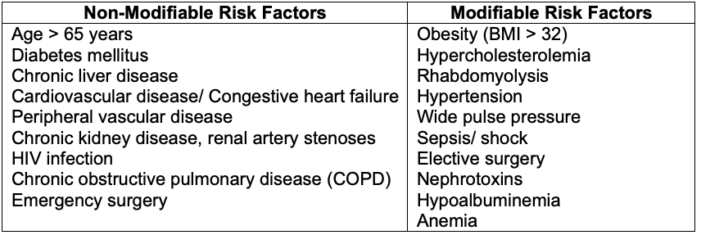

- Risk factors for AKI are listed in Table 2.

Table 2. Risk factors for acute kidney injury

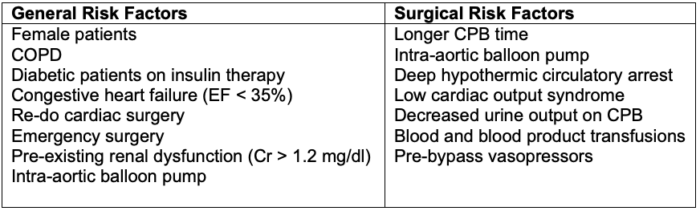

- Risk factors for perioperative AKI following cardiac surgery are listed in Table 3.

Table 3. Risk factors for perioperative AKI following cardiac surgery. Abbreviations: COPD = chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, EF = ejection fraction, CPB = cardiopulmonary bypass.

Etiology of AKI

Prerenal AKI

- Prerenal AKI accounts for up to 60% of cases. It results from functional adaptation to hypoperfusion of functionally normal kidneys.2

- Common causes include:

- Hypovolemia secondary to excess fluid losses, diuretic use, or hemorrhage

- Impaired cardiac function leading to a decrease in effective circulating volume

- Systemic vasodilation from sepsis, anaphylaxis, or administration of anesthesia

- Renal vasoconstriction from drugs like calcineurin inhibitors, iodinated contrast, and hepatorenal syndrome

- Efferent arteriolar vasodilation from angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors and angiotensin receptor blockers3

Intrinsic Renal AKI

- Intrinsic renal AKI accounts for up to 40% of cases of AKI and occurs due to parenchymal damage and is categorized based on the location of the injury.2

- Acute tubular necrosis (ATN) is the most common intrinsic AKI. It results from prolonged ischemia, dose-dependent nephrotoxicity from drugs (aminoglycosides, vancomycin, amphotericin B), and toxins like myoglobin and ethylene glycol.

Medications commonly associated with ATN include:4

-

- Aminoglycosides (tobramycin, gentamycin)

- Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) (ibuprofen, naproxen, ketorolac, celecoxib)

- Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (losartan, valsartan, candesartan, irbesartan)

- Amphotericin B

- Cisplatin

- Foscarnet

- Pentamidine

- Tenofovir

- Vancomycin

- Zoledronic acid

Medications requiring dose adjustment or cessation in AKI include:4

-

- Analgesics (morphine, meperidine, gabapentin, pregabalin)

- Antiepileptics (lamotrigine)

- Antivirals (acyclovir, ganciclovir, valganciclovir)

- Antifungals (fluconazole)

- Antimicrobial (almost all antimicrobials, except azithromycin, ceftriaxone, doxycycline, linezolid, moxifloxacin, nafcillin, rifampin)

- Diabetic agents (sulfonylureas, metformin)

- Allopurinol

- Baclofen

- Digoxin

- Lithium

- Low-molecular-weight heparin

- Novel anticoagulants.

- Acute interstitial nephritis (AIN) occurs due to hypersensitivity reactions to medications like β-lactam antibiotics, proton pump inhibitors, and NSAIDs, and hereditary AIN.3

- Glomerulonephritis can be immune-mediated (IgA nephropathy, Lupus nephritis), infectious (post-streptococcal, infective endocarditis), or drug-related.

- Vascular causes include large vessel disease (bilateral renal artery stenoses, bilateral renal vein thrombosis) and small vessel diseases (vasculitis, hemolytic uremic syndrome, thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura).

Postrenal AKI

- Postrenal AKI comprises a small proportion of AKI. It occurs from urinary tract obstruction.2

- Common causes include:

- Extrarenal obstruction from bladder cancer, prostatic hypertrophy, neurogenic bladder, external compression of kidneys from tumors, pregnancy, etc.

- Intrarenal obstruction due to nephrolithiasis, blood clots, papillary necrosis, etc.

Clinical Signs and Symptoms

- AKI induces multiorgan dysfunction due to the accumulation of uremic toxins, fluid overload, electrolyte, and acid-base abnormalities. It is more frequently seen in oliguric AKI.

- Patients can present with nausea, vomiting, encephalopathy, seizures, hypertension, arrhythmias, coagulopathy, and infections.

- Patients with AKI can have thrombocytopenia and an increased risk of bleeding. However, this may not be due to decreased platelet function.5

- In contrast, patients with CKD or end-stage renal disease exhibit uremic bleeding due to defects in platelet aggregation and adhesiveness from uremic toxins, increased nitrous oxide, prostacyclin, abnormal von Willebrand factor, etc. It presents as mucocutaneous bleeding and easy bruising.

Diagnosis and Management of AKI

In addition to a focused history and physical examination, evaluation for all possible causes of AKI is warranted. This may include, but is not limited to:

- Comprehensive laboratory testing – serum creatinine, cystatin, urea, electrolytes, glucose, liver profile, complete blood count, hepatitis, and HIV panels

- Common electrolyte abnormalities include elevated potassium, phosphate, and magnesium and decreased sodium and calcium. Additional laboratory abnormalities include elevated urea, creatinine, uric acid, sulfate, phosphate, phosphorous, lipids, cholesterol, neutral fates and some amino/organic acids.

- Urine studies – including urine output, routine analysis, chemistry, and microscopic examination for casts, red cells, eosinophils, and crystals

- Immunological studies – ex. antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies, antinuclear antibodies, anti-dsDNA antibodies, complement factors, serum electrophoresis to rule out monoclonal gammopathy

- Imaging – renal ultrasound and computed tomography of abdomen/ pelvis for urolithiasis or masses. Renal biopsy may be necessary in severe AKI with an unclear cause.

- Newer biomarkers, such as neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin (NGAL), kidney injury molecule-1, liver fatty acid binding protein, tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase 2, and insulin-like growth factor-binding protein 7 (TIMP-2*IGFBP7), which are under investigation, may aid with the early diagnosis of AKI.

- Finally, early nephrology consultation is highly beneficial in patients with higher stages of AKI, AKI of unclear cause, AKI unresponsive to supportive measures, patients with organ transplants, and when initiating renal replacement therapy.4

Treatment of AKI

Prevention is the best treatment for AKI. Identifying high-risk patients, avoiding hypotension and exposure to nephrotoxins, and optimizing hemodynamics and volume are crucial.2

- Correction of hypovolemia with individualized fluid resuscitation and diuresis if volume overload is present

- Vasopressor and ionotropic support to maintain mean arterial pressure > 65 mmHg.4

- Discontinuation of potential nephrotoxins and dose adjustment for renally excreted medications.4

- Supportive care, correcting acid-base/ electrolyte disturbances, ensuring adequate oxygenation, and optimizing nutrition and glycemic control.

- The treatment of uremic bleeding includes dialysis, desmopressin 0.3- 0.4 mcg/kg IV or SC, conjugated estrogen 0.6 mg/kg IV daily for 5 days, erythropoietin or blood transfusion to maintain hematocrit > 30%, and cryoprecipitate.

- Renal replacement therapy (RRT): If conservative measures are ineffective, continuous or intermittent RRT becomes necessary. Common modalities of RRT include:

- Continuous venovenous hemofiltration

- Continuous venovenous hemodialysis

- Continuous venovenous hemodiafiltration

- Intermittent hemodialysis

- Slow continuous ultrafiltration

- Sustained low-efficiency dialysis and

- Peritoneal dialysis2

- Indications for urgent RRT include:4

- Severe refractory hyperkalemia (K+ > 6.5 mEq/L)

- Severe refractory metabolic acidosis (pH < 7.2 despite normal or low PaCO2)

- Volume overload refractory to diuretic therapy

- Severe oliguria or anuria (urine output < 200 mL over 12 hours)

- Complications of uremia, like encephalopathy, pericarditis, neuropathy

- Removal of dialyzable toxins like lithium, ethylene glycol, etc.

- Post-AKI care should include follow-up with a nephrologist within 3 months of the AKI episode, medication reconciliation, nephrotoxic avoidance, and education to prevent progression to CKD.2

References

- Ronco C, Bellomo R et al. Acute kidney injury. The Lancet. 2019; 394(10212): 1949-64. PubMed

- Gameiro J, Fonseca JA, Outerelo C, et al. Acute kidney injury: From diagnosis to prevention and treatment strategies. J Clin Med. 2020;9(6):1704. PubMed

- Goyal A, Daneshpajouhnejad P, Hashmi MF, et al. Acute kidney injury. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2025 Jan-. Link

- Mercado MG, Smith DK, Guard EL. Acute kidney injury: Diagnosis and management. Am Fam Physician. 2019;100(11):687-694. PubMed

- Jensen JLS, Hviid CVB, Hvas CL, Christensen S, Hvas AM, Larsen JB. Platelet Function in Acute Kidney Injury: A Systematic Review and a Cohort Study. Semin Thromb Hemost. 2023 Jul;49(5):507-522. PubMed

Other References

Copyright Information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.