Copy link

Acute Coronary Syndrome

Last updated: 08/07/2025

Key Points

- Acute coronary syndrome (ACS) is characterized by decreased blood flow to the myocardium.

- Patients can be broadly categorized as having a ST elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) or non-ST elevation acute coronary syndrome (NSTE-ACS). (NSTEMI and unstable angina).

- Electrocardiogram (ECG) and biomarkers, such as troponins, are used to distinguish between the two.

- Prompt cardiac catheterization for revascularization is the mainstay treatment to reduce mortality.

Introduction

- ACS is a broad term that refers to a group of diseases involving sudden reduced blood flow to the myocardium. It can be broadly categorized as ST-elevation myocardial infarctions and non-ST-elevation ACS (NSTEMI and unstable angina) based on ECG findings and cardiac biomarkers.1

- Coronary artery disease (CAD) affects 15.5 million people in the United States, and cardiovascular disease is the leading cause of death worldwide.1

- Worldwide, it is estimated that 7 million people are diagnosed with ACS each year. In the US, more than 1 million people are hospitalized due to it.2

- Patients with CAD are at an increased risk of perioperative cardiac complications compared to those without the disease.1

- The most common risk factors for ACS are smoking, hypertension, diabetes, hyperlipidemia, obesity, male sex, use of vasoactive substances, and physical inactivity.1

- The most common risk factors for perioperative myocardial injury after non-cardiac surgery (MINS) are listed below.3

- age ≥65 years;

- coronary artery or peripheral artery disease;

- diabetes;

- kidney dysfunction;

- elevated N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide level;

- baseline ST-T wave changes;

- significant perioperative hemorrhage, and;

- specific types of surgery (e.g., emergency, vascular surgery).

- In hospitalized adults (≥ 45 years of age) undergoing noncardiac surgery, MINS occurs in 15-20% of this population. A diagnosis of MINS is associated with both a short-term and a long-term increased morbidity and mortality.3

Pathophysiology of Perioperative ACS

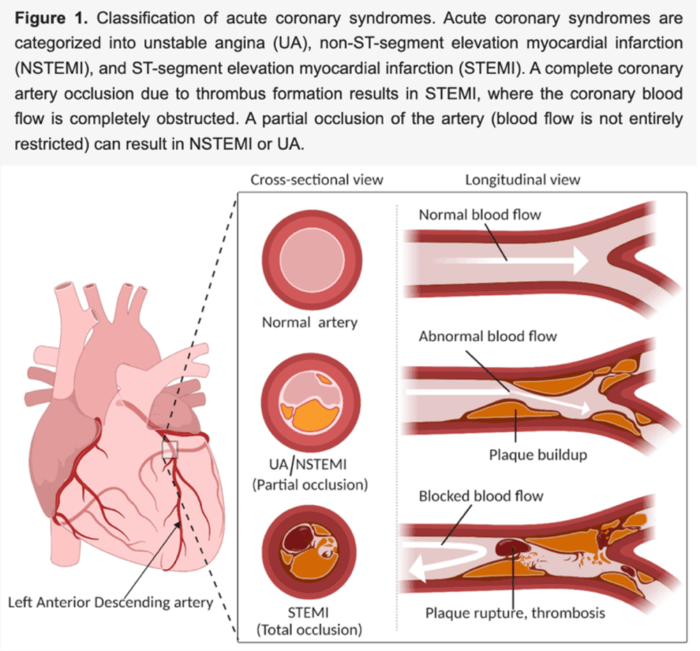

- ACS is a type of coronary heart disease and most often occurs due to coronary artery obstruction from plaque buildup, the rupture or erosion of atherosclerotic plaques, and thrombus formation. Other less common causes include calcified nodules, coronary vasospasm, spontaneous coronary artery dissection, coronary embolism, and myocardial infarction with non-obstructive coronary arteries (e.g., demand ischemia).2

- About 70% of perioperative ACS is NSTEMI, with demand ischemia being a frequent cause in the perioperative period.2

- Most perioperative ACS cases stem from preexisting coronary artery disease, even if previously asymptomatic. Surgery triggers physiological stress that can expose underlying vulnerabilities.4

- Similar to ACS, MINS is due to demand ischemia (supply-demand mismatch) or thrombus formation.3

Type 1 Myocardial Infarction (MI)

- Caused by acute plaque rupture or erosion in coronary vessels with atherosclerosis.

- The body’s stress response, hypercoagulable state, and increased disruption during surgery can provoke thrombus formation, leading to partial or complete occlusion.4

- Less common than type 2 MI in the perioperative setting, but it carries a higher long-term risk.4

Type 2 MI

- Much more common postoperatively, it is caused by an oxygen supply-demand mismatch rather than a thrombus.4

- Contributing factors include anemia, hypoxia, hypotension, tachyarrhythmias, or increased myocardial work.4

- Often occurs in patients with fixed coronary lesions who cannot compensate during systemic stress, such as surgery.

- The prognosis remains serious, but management focuses on addressing the underlying cause.

Takotsubo (Stress) Cardiomyopathy4

- Acute myocardial dysfunction resembling ACS but typically with normal coronary vessels.

- More common in older women and typically triggered by physical/emotional stress.

- Manifests with regional wall motion abnormalities similar to anterior MI.

Myocarditis

- Inflammation of the myocardium that can present like ACS but is rare in the perioperative context.

- The most common contributors are viral infections, immune response, or drug toxicity.4

STEMI vs NSTEMI in ACS: Clinical Categories

- STEMI: Represents transmural ischemia from complete arterial occlusion, often due to plaque rupture; urgent reperfusion is essential.4

- NSTEMI: Reflects subendocardial ischemia due to partial occlusion, plaque erosion, or supply-demand imbalance; ECG may be nonspecific.4

Figure 1. Classifications of ACS. Source: Surendran A, et al. Defining acute coronary syndrome through metabolomics. Metabolites. 2021; 11(10):685. CC BY 4.0. PubMed

Initial Diagnosis and Management of ACS

- Patients in the perioperative period oftentimes may not present with the classic ACS symptoms of chest pain, shortness of breath, diaphoresis, dizziness, or nausea. This is due to the use of anesthetic, analgesic, or amnestic agents.2

- Therefore, it is important to have a low threshold of suspicion in patients with risk factors of ACS and MINS.

- In patients at high risk for MINS (those presenting with one or more risk factors), obtaining troponin levels 6-12 hours after surgery and daily for three days after surgery is recommended.3

- Diagnosis of perioperative MINS requires 2 major criteria:3

- The patient has undergone noncardiac surgery within the past 30 days and presents with elevated surveillance troponin levels and a documented trend in troponin levels suggestive of acute injury.

- Exclusion of nonischemic causes of troponin elevation.

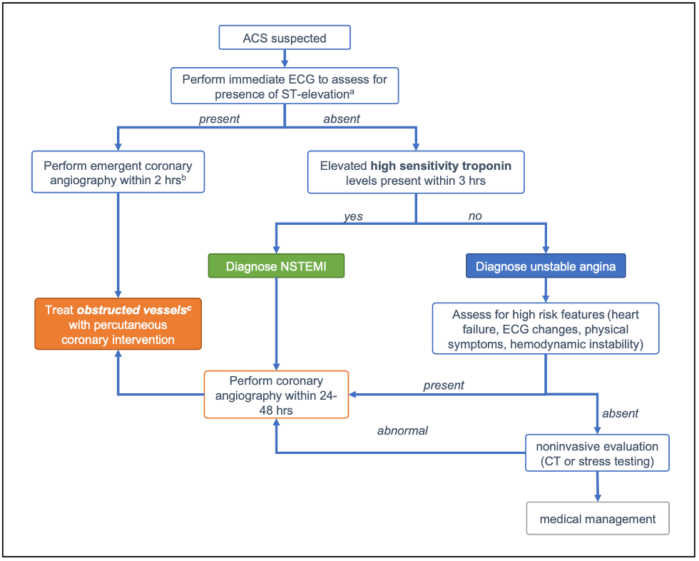

aTreat with antiplatelets and anticoagulants in the case of suspected ACS as early as possible bTransfer facility and treat with fibrinolytics (alteplase, reteplase, tenecteplase or streptokinase) and PCI within 24 hours cTreat with medical management in the absence of obstructed vessels

Figure 2. Proposed treatment algorithm for suspected ACS using ECG and repeat troponin levels to guide management. Adapted from: Initial diagnosis and management of ACS (Bhatt DL, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of acute coronary syndromes: a review. JAMA. 2022;327(7):662-675. PubMed

ACS Evaluation and Triage2

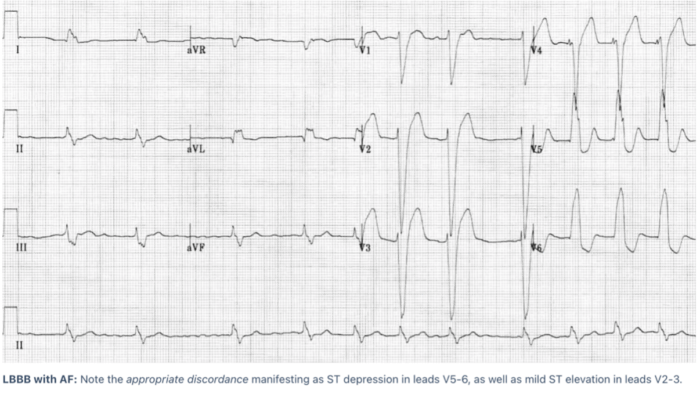

- Get an ECG quickly: If a patient presents with chest pain, an ECG should be performed within 10 minutes. If there is ST-elevation or a new left bundle branch block, they likely have a STEMI and need emergency angiography and percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI), ideally within 2 hours.2

Figure 3. Left bundle branch block (LBBB) with mild ST elevation in leads V2-3 with ST depression in leads V5-6. Source: Burns E, Buttner R. Left Bundle Branch Block (LBBB). ECG Library Diagnosis. LITFL (Life in the Fast Lane). Published October 8, 2024. Accessed July 15, 2025. CC BY 4.0 Link

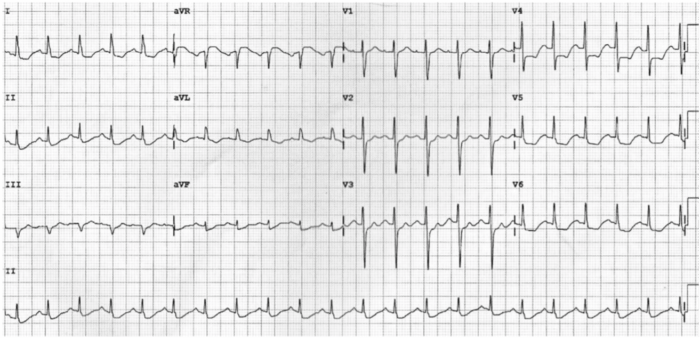

- Most ACS cases don’t have ST elevation: In NSTEMI or unstable angina, you might see ST depressions, T-wave inversions, both, or even a normal ECG—so don’t rely on the ECG alone to rule out ACS.2

Figure 4. Widespread ST depression due to subendocardial ischemia Source: Burns E, Cadogan M. Myocardial ischaemia. ECG Library Diagnosis. LITFL (Life in the FastLane). Published October 8, 2024. Accessed July 28, 2025. CC BY 4.0 Link

- High-sensitivity troponins are highly sensitive: If troponins are normal at presentation and still normal 1-3 hours later, you can rule out ACS with high confidence (~99% negative predictive value).2

- Echocardiography helps in unclear cases: For patients with NSTEMI symptoms or ongoing pain, bedside echo can detect wall motion abnormalities, helping identify those who need urgent angiography even in the absence of ECG changes.2

- Computed tomography (CT) angiography can be a noninvasive option: In low-to-intermediate risk patients (normal ECG/troponin, no instability), a normal coronary CT angiogram can rule out significant coronary disease and avoid unnecessary testing, with high sensitivity (~96.5%) and negative predictive value (~91%).2

- Diagnosing ACS in the perioperative period may be challenging, as patients under general anesthesia do not present with chest pain, and those in the postoperative areas do not always experience chest pain.5

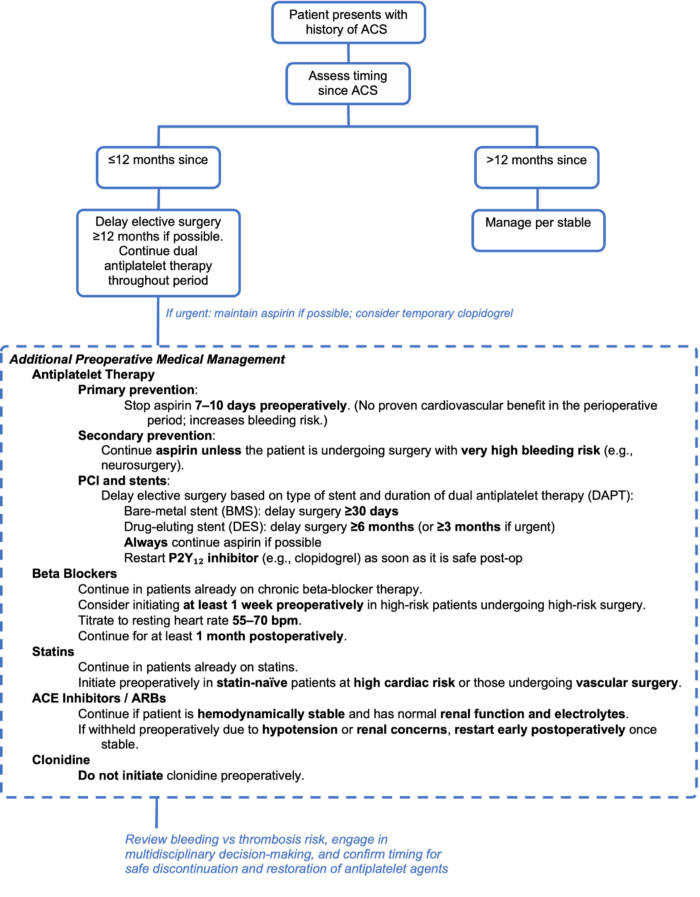

Preoperative Evaluation and Management

Figure 5. Algorithm for perioperative management of ACS.6

Intraoperative and Postoperative Management

- Demand ischemia is a major culprit of ACS. ECG changes during general anesthesia may be present (ST depression). The goal is to decrease myocardial oxygen demand while improving myocardial oxygenation (Table 1).

- Treat tachycardia and hypertension (consider narcotics and deepening the anesthetic if caused by pain and inadequate anesthesia; intraoperative beta blockers may be needed, along with vasodilators)

- Treat arrhythmias

- Treat hypotension with vasopressors and fluids if not hypervolemic

- Treat anemia with blood products to maintain a hemoglobin >8g/dL

- Discussion should be had with the surgeon regarding completing vs. aborting surgery if ECG changes persist despite management strategies or the patient becomes unstable.

- Cardiology consultation for cardiac catheterization is recommended for patients with NSTE-ACS, as they often benefit from revascularization.

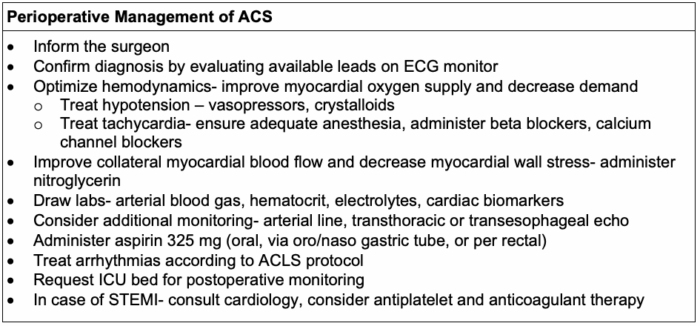

Table 1. Perioperative management of ACS.7

An appraisal of the 2023 European Society of Cardiology Guidelines for the Management of Acute Coronary Syndrome suggests the following.8

- Think of ACS as a continuum instead of discrete categories (STEMI vs NSTEMI)

- Treatment should be more individualized and not “one-size-fits-all.”

- Imaging and biomarkers play a bigger role in guiding therapy.

- Earlier angiography is recommended when indicated, but should be tailored, especially for non-ST-elevation acute coronary syndromes.

- Emerging therapies like low-dose colchicine could impact outcomes beyond traditionally used antithrombotic medications.

The 2025 ACC/AHA/ACEP/NAEMSP/SCAI guidelines offer additional recommendations to improve mortality in patients with multivessel cardiac disease9:

- STEMI patients with multivessel disease should undergo PCI of the culprit (infarct-related) artery first, followed by PCI of other significantly narrowed vessels during the same procedure.

- NSTE-ACS patients who are hemodynamically stable should have the culprit lesion treated first. PCI of other significant lesions can be performed either simultaneously or in a staged approach to reduce the risk of future major adverse cardiac events.

- Patients in cardiogenic shock (hemodynamically unstable) should not undergo multivessel revascularization during the acute procedure due to associated increased mortality and risk of renal injury.

References

- Singh A, Museedi AS, Grossman SA. Acute coronary syndrome. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2025. Link

- Bhatt DL, Lopes RD, Harrington RA. Diagnosis and treatment of acute coronary syndromes: a review. JAMA. 2022;327(7):662-675. PubMed

- Wijeysundera DN. Perioperative myocardial infarction or injury after noncardiac surgery. UpToDate. Link

- Helwani MA, Amin A, Lavigne P, et al. Etiology of acute coronary syndrome after noncardiac surgery. Anesthesiology. 2018;128(6):1084-1091. PubMed

- Ruetzler K, Smilowitz NR, Berger JS, et al. Diagnosis and management of patients with myocardial injury after noncardiac surgery: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2021;144(19): e287-e305. Link

- Tabit CE, Nathan S. Management of perioperative acute coronary syndromes by mechanism: a practical approach. Int Anesthesiol Clin. 2021;59(1):61-65. PubMed

- Steyn J, Dorfling J. Acute coronary syndrome. In: Crisis Management in Anesthesiology. Gaba DM, et al (eds). Second edition. 2015. Elsevier Saunders. 137-140.

- Licordari R, Costa F, Garcia-Ruiz V, et al. The evolving field of acute coronary syndrome management: a critical appraisal of the 2023 European Society of Cardiology guidelines for the management of acute coronary syndrome. J Clin Med. 2024;13(7):1885. PubMed

- Kumbhani DJ, Cibotti-Sun M, Moore MM. 2025 Acute Coronary Syndromes Guideline-at-a-Glance. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2025;85(22):2128-2134. Link

Copyright Information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.