Copy link

Discogenic Pain: Radiculopathy vs Referred Pain

Last updated: 05/08/2025

Key Points

- Degenerative changes of the intervertebral discs begin in the second decade of life and are believed to be a major cause of nonspecific low back pain.

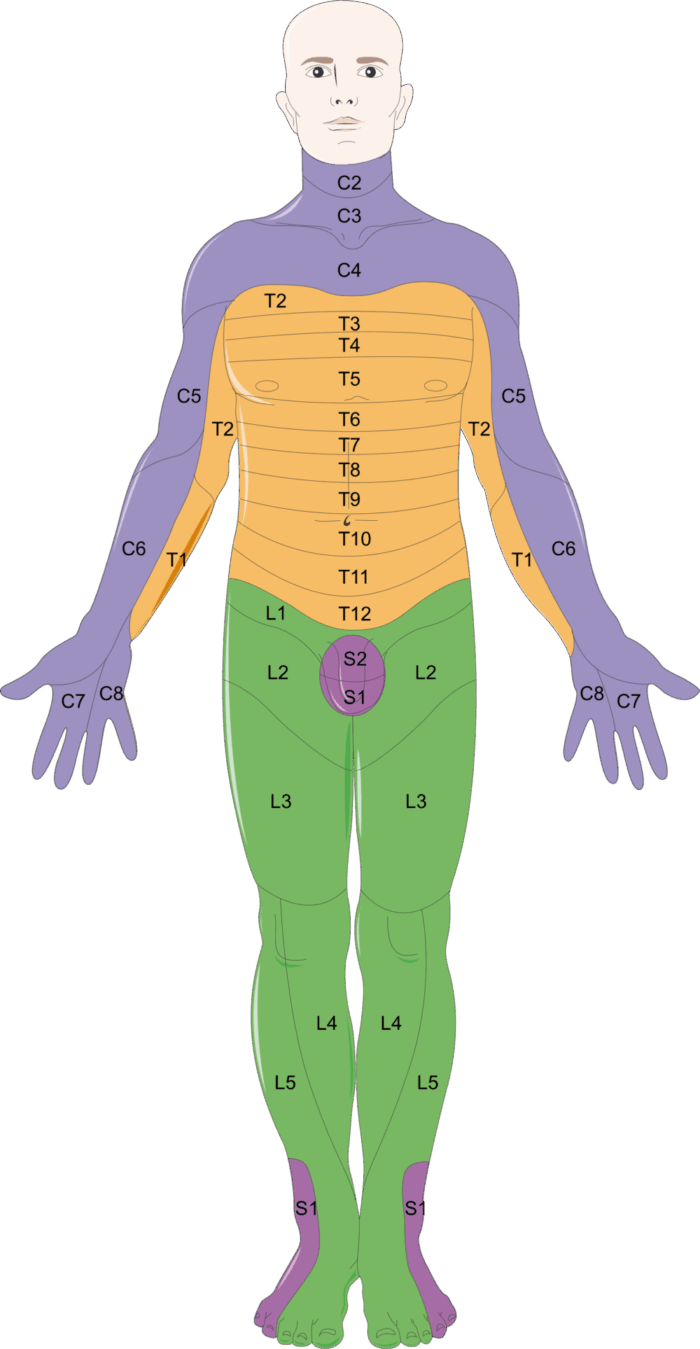

- Radiculopathy follows a dermatomal pattern with motor, sensory, and/or reflex abnormalities appreciated on a physical exam.

- Referred lumbar discogenic pain is typically experienced in the thigh, above the level of the knee.

Degenerative Disc Changes

- Neck pain and low back pain are common causes of disability and morbidity, with costs estimated to exceed 100 billion dollars annually in the United States.1 Approximately 45% of low back pain cases have appeared to be discogenic in nature, with degenerative changes beginning in the second decade of life.2,3

- The proposed disc degenerative cascade is as follows:1,2

1. Vertebral endplate damage preceding disc degeneration

2. Nucleus pulposus matrix changes with fragmentation of proteoglycans

3. Decrease in nucleus pulposus water volume and decline of viable disc cells

4. Radial or full-thickness tearing of the annulus fibrosis

5. Ingrowth of peripheral blood vessels and nerve fibers - After disc degeneration begins with subsequent loss of disc height, greater axial load is transmitted to the facet joints, resulting in the development of spondylosis with possible facet arthropathy, ligamentum flavum hypertrophy, and osteophyte formation.4

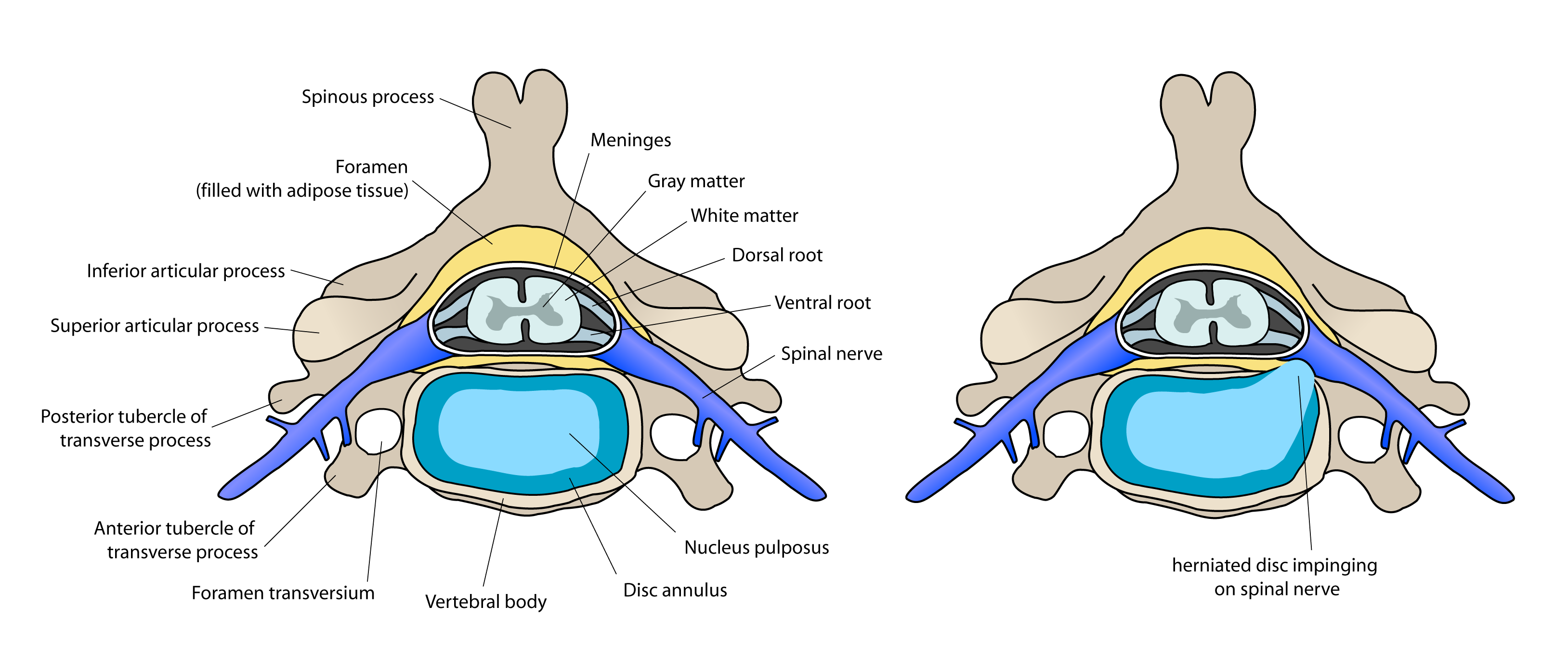

Figure 1. Cervical vertebra and disc anatomy demonstrating nerve impingement. Source: Wikimedia. Debivort CC BY-SA 3.0 Link

Radiculopathy

- Radiculopathy is nerve dysfunction caused by compression of a nerve root from either an intravertebral disc herniation or from foraminal encroachment secondary to chronic degenerative changes such as loss of disc height or facet hypertrophy.4,5 Nerve dysfunction can be identified on a physical exam as a motor, sensory, and/or reflex abnormality.5

- The most commonly affected levels in the lumbar spine include L4/5 and L5/S1, resulting in L5 or S1 radiculopathies4 (Figure 2). When these root levels are involved, symptoms are generally reported to begin in the lumbar spine with radiation down the posterior thigh to the lower leg and/or foot. In the cervical spine, the most commonly affected nerve roots are C6 and C7, with symptoms radiating into the forearm and hand.5

Characteristics of Radiculopathy

- Radiculopathy is often described as a burning, aching, throbbing, dull, or sharp pain.

- Symptoms typically follow a segmental dermatomal distribution.

- Cervical radiculopathy symptoms can be recreated on a physical exam with the Spurling’s maneuver. Link

- Lumbar radiculopathy symptoms can be recreated on a physical exam with a straight leg raise test. Link

- In general, 4-6 weeks of conservative management is recommended for individuals experiencing radicular symptoms in the absence of red flags (bowel/bladder changes, night pain, weight loss, intravenous drug use, etc.). Conservative management includes nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, physical therapy, and avoiding the activity that causes the pain.

- After this time, further workup, including magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and electromyography (EMG), may be warranted.4,5 It should be noted that up to 30-40% of asymptomatic individuals may have evidence of lumbar disk herniations on MRI.4

- EMG and nerve conduction studies are useful in evaluating suspected radiculopathy due to the ability to:4

- differentiate between radiculopathy vs peripheral neuropathy vs plexopathy;

- determine the severity and chronicity of radiculopathy; and

- evaluate the integrity of nerve roots as well as peripheral nerves.

Discogenic Referred Pain

- Discogenic referred pain develops secondary to degenerative changes of the intervertebral disc.2 A healthy intervertebral disc is innervated by the sinuvertebral nerve only on the outermost third of the annulus fibrosis.2,3 It is thought that discogenic pain can be experienced once a tear in the annulus fibrosis reaches the outer third, where this innervation occurs.2 In high-grade, chronically degenerated discs the peripheral nerve fibers may penetrate more deeply to the level of the nucleus pulposus.2,3 Once nerve fibers and nociceptors have penetrated, the disc may become sensitized to normal mechanical axial loads.2

- In addition to disc sensitization, there is evidence that inflammatory mediators such as IL-6, matrix metalloproteinases, and prostaglandin E2 can be released from the nucleus pulposus.2,5 These inflammatory mediators may be a source of pain as they affect adjacent epidural structures.2

- Risk factors for disc degeneration and discogenic pain include:3,4

- Smoking;

- repetitive heavy lifting; and

- genetic susceptibility.

Characteristics of Discogenic Referred Pain2

- Discogenic referred pain presents as persistent pain, which worsens with axial load and improves with laying down.

- Radiation of lumbar discogenic symptoms can be experienced in the anterior, lateral, or posterior thigh.

- L3/4 – Anterior thigh

- L4/5 – Lateral to posterior thigh

- L5/S1 – Posterior thigh

- Pain can worsen when straightening from flexion or with an increase in intradiscal pressure (coughing, straining, etc.).

- No typical characteristics or specialty tests have been established on the physical exam.

Imaging/Diagnostic Tests

- MRI can be an effective tool for evaluating intervertebral discs with potential findings of:

- high-intensity zones within the discs;

- loss of disc height; and

- degenerative endplate changes (also known as Modic changes).

- The importance of these MRI findings in determining discogenic pain has been debated.2,3

- Provocative discography has been regarded as the gold standard for the evaluation of discogenic pain, but a clear definition of diagnosis and subsequent treatment has not yet been established.1,3 Complications of discography include infection and the risk of accelerated disc degeneration, likely secondary to disc puncture.1

References

- Malik, KM, Cohen SP, Walega DR, et al. Diagnostic criteria and treatment of discogenic pain: a systematic review of recent clinical literature. Spine J. 2013;13(11):1675-89. PubMed

- Kallewaard, JW, Terheggen MAMB, Groen GJ, et al. Discogenic low back pain. In: Zundert, JV, Patijn, Hartrick C, et al. Evidence‐Based Interventional Pain Medicine: According to Clinical Diagnoses. John Wiley & Sons; 2012: 107-22.

- Hurri H, Karppinen J. Discogenic pain. Pain. 2004;112(3):225-228. PubMed

- Tarulli AW, Raynor EM. Lumbosacral radiculopathy. Neurol Clin. 2007;25(2):387-405. PubMed

- Carette S, Fehlings MG. Clinical practice. Cervical radiculopathy. N Engl J Med. 2005;353(4):392-9. PubMed

Copyright Information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.