Copy link

Blood Transfusion Reactions, TRALI, and TACO

Last updated: 05/10/2023

Key Points

- The signs and symptoms of transfusion reactions are often masked when a patient is under general anesthesia.

- Anesthesiologists should be familiar with the differential diagnosis of transfusion reactions and their management.

- Active vigilance is important, and when in doubt, the transfusion should be discontinued.

- Transfusion-associated circulatory overload (TACO) and transfusion-related acute lung injury (TRALI) are common causes of morbidity and mortality after a blood transfusion.

Introduction

- Blood transfusions are not without risk and can result in severe complications such as transfusion reactions, electrolyte abnormalities, transmission of infections, and coagulopathy.

- In this summary, we will focus on blood transfusion reactions, mostly immunologic reactions. Other complications from blood transfusions will be covered in a separate summary.

- Transfusion reactions may be seen in 1-3% of all transfusions.1 Pediatric patients have a higher rate of transfusion reactions than adults, especially with transfusion of red blood cells (RBC) and platelets.2

- Transfusion reactions have a broad spectrum of presentation and can range from mild symptoms to life-threatening events.3

- Prompt recognition and management is critical to improve patient outcomes.

- Transfusion reactions may be difficult to detect under general anesthesia as the classical signs and symptoms are often masked.

- Anesthesiologists should be vigilant and periodically monitor for signs like rash, increased airway pressures, fever, dark urine, unexplained hypotension, hypoxemia, and signs of volume overload.

- Transfusion reactions most likely to be encountered by anesthesiologists include transfusion-related acute lung injury (TRALI), transfusion-associated circulatory overload (TACO), febrile nonhemolytic transfusion reactions (FNHTR) and urticarial/anaphylactic reactions.4

Categories

- Transfusion reactions can be divided into acute (within 24 hours of the start of the transfusion) or delayed (after 24 hours and up to 30 days).

- The etiology can either be immunologic (hemolytic reactions, febrile, TRALI) or nonimmunologic (TACO).

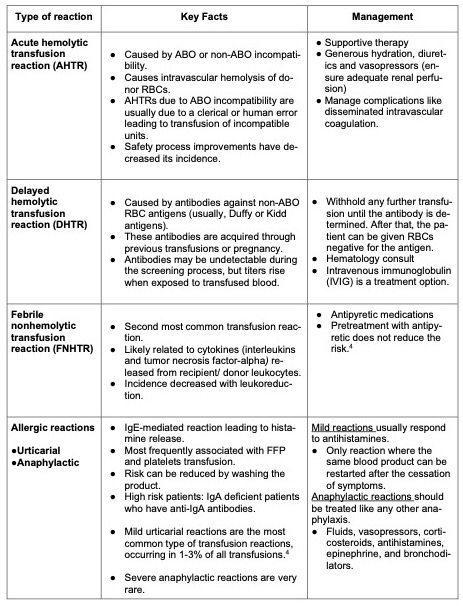

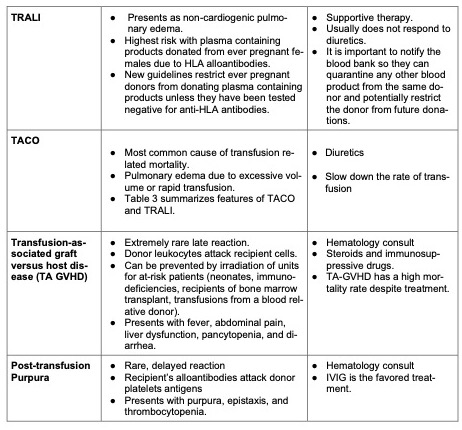

- Table 1 summarizes commonly encountered transfusion reactions and their management.

Table 1. Summary of common transfusion reactions.

Presentation

- There can be significant overlap in the clinical presentation of different reactions and a blood bank specialist should be consulted when in doubt.

- Small variations in vital signs are usually not a transfusion reaction.

- AHTR: Potentially fatal reaction. Presents with flank pain, dyspnea, fever, and hypotension. Under anesthesia, patients are more likely to present with hypotension, fever, oozing from intravenous access sites, and dark urine. If not treated immediately, it can lead to disseminated intravascular coagulopathy, renal failure, shock, and death.

- DHTR: Presents with jaundice, dark urine, back pain, and fever; usually days to weeks posttransfusion. The first sign is often a hemoglobin level that falls or fails to increase posttransfusion. Laboratory work will typically show elevated unconjugated bilirubin and lactate dehydrogenase and decreased serum haptoglobin.

- Allergic Reactions: most reactions are mild with cutaneous symptoms, like rash, itching, and urticaria, without systemic manifestation. Anaphylaxis presents with hypotension, angioedema, respiratory distress, and bronchospasm.

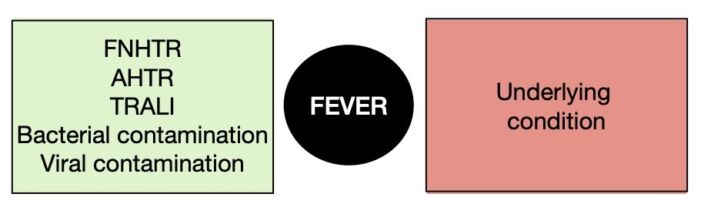

- FNHTR: Usually, presents with fever during or within 4 hours of transfusion. For its diagnosis there should be an increase in temperature of at least 1°C and a fever greater than 38°C. The diagnosis can also be made with the presence of chills and rigors in an immunocompromised patient, without fever. Keep in mind that other reactions can also present with fever (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Differential diagnosis of a fever during a blood transfusion.

TRALI

- TRALI is a clinical diagnosis that includes a combination of acute lung injury and noncardiogenic pulmonary edema.

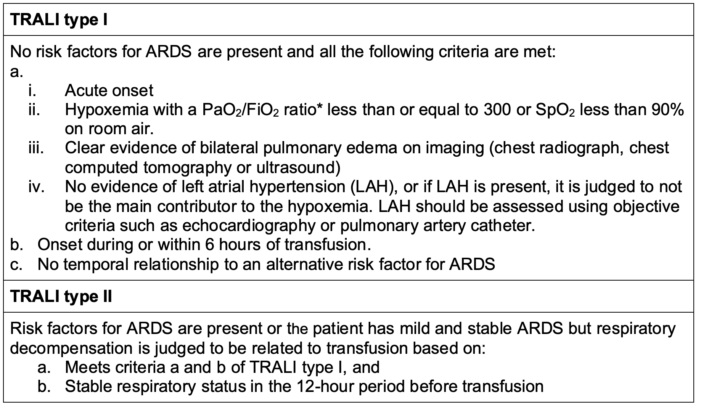

- In 2005, the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute working group proposed a definition for TRALI based on a clear temporal relationship between the onset of hypoxemia and transfusion.5 In 2019, a Delphi panel proposed a modified classification scheme that describes two types of TRALI based on the presence of risk factors for acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) (Table 2).6

Table 2. New TRALI definition. * If the altitude is higher than 1000 meters, a correction factor should be used (PaO2/FiO2 x barometric pressure/760). Adapted from Vlaar APJ, et al. A consensus redefinition of transfusion-related acute lung injury. Transfusion. 2019;59(7): 2465.6

- The incidence of TRALI is probably underestimated, but there has been a decrease since the adoption of TRALI mitigation strategies such as avoiding plasma containing components from multiparous female donors unless they have tested negative for anti-HLA antibodies.

- TRALI was the leading cause of transfusion-related mortality in the United States until 2016, when it was overtaken by TACO as the most common cause of transfusion-associated mortality.7,8

- The proposed mechanism of TRALI involves activation of recipient neutrophils, possibly by anti-HLA or antineutrophil antibodies, causing pulmonary endothelial damage.

- According to a “two-hit” theory, the first hit is the trauma/surgery/injury causing neutrophil sequestration and priming in the lung microvasculature, and the second hit is the activation of recipient neutrophils by a factor in the blood product.8

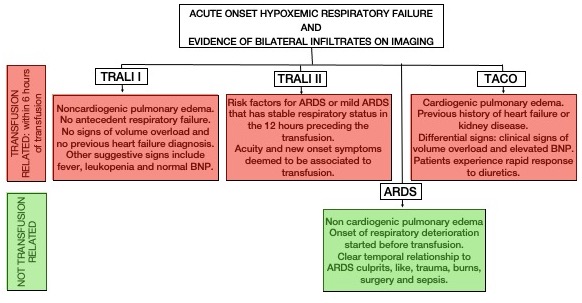

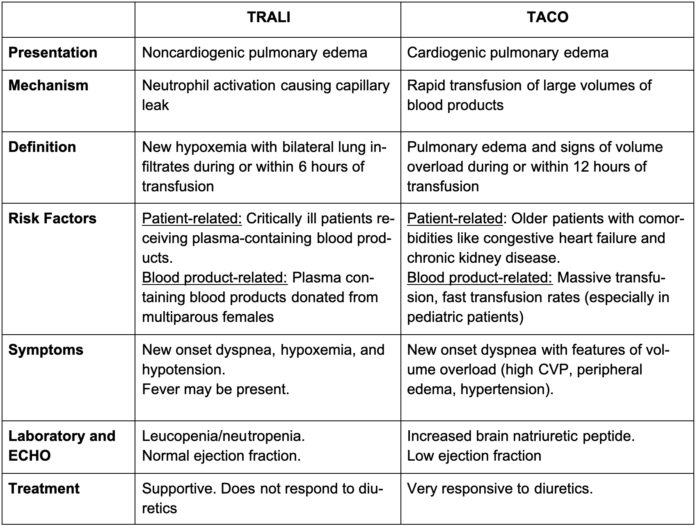

- The two main differential diagnosis include TACO and ARDS (Figure 2 and Table 3).

- ARDS is the appropriate diagnosis if the signs and symptoms were present 12 hours preceding the transfusion.

- Clinically, it can be very challenging to differentiate TRALI, TACO, or ARDS and they can be interposed.

- Management is supportive and include oxygen supplementation, noninvasive positive pressure ventilation and lung protective ventilation if intubated (same management as ARDS).

- Corticosteroids are not indicated.

- Any suspicion of TRALI should be immediately reported to the blood bank and transfusion specialist.

- Majority of the patients will require admission to the intensive care unit, but recovery generally occurs within 24 to 48 hours of symptom onset.

TACO

- Very similar presentation to TRALI but develops primarily due to large volume of transfusion in a short period of time, combined with underlying cardiovascular or renal disease.

- Patients have signs and symptoms of volume overload:

- Hypertension, high central venous pressure, peripheral edema, and jugular vein distension

- Previous diagnosis of heart failure or kidney disease

- Elevated brain natriuretic protein (BNP) levels

Figure 2. Acute pulmonary edema and blood transfusion.

Table 3. Comparison between TRALI and TACO. Response to diuretics is one of the key distinguishing features. Adapted from Kleinman S, Kor DJ. Transfusion-related acute lung injury. In: Post T, ed. UpToDate; 2023.8

Management

- The transfusion should be stopped as soon as there is a suspicion of an adverse reaction.

- Treatment includes supportive care with fluids, supplemental oxygen, ventilatory support, antipyretics, antihistamines, and vasopressors, depending on the presentation (Table 1).

- The blood bag should not be discarded. A blood and urine sample should be collected from the patient.

- The remaining blood product, blood tubing, and posttransfusion blood sample should be sent to the blood blank for workup and a local report should be filed.

References

- Hendrickson JE, Roubinian NH, Chowdhury D, et al. Incidence of transfusion reactions: a multicenter study utilizing systematic active surveillance and expert adjudication. Transfusion. 2016; 56(10):2587-96. PubMed

- Vossoughi S, Perez G, Whitaker BI, et al. Analysis of pediatric adverse reactions to transfusions. Transfusion. 2018;58(1):60-9. PubMed

- Maxwell MJ, Wilson MJ. Complications of blood transfusion. Continuing Education in Anaesthesia and Critical Care. BJA Education. 2006; 6:225-9. Link

- Gilliss BM, Looney MR, Gropper MA. Reducing noninfectious risks of blood transfusion. Anesthesiology. 2011; 115:635-49. PubMed

- Toy P, Popovsky MA, Abraham E, et al. Transfusion-related acute lung injury; definition and review. Crit Care Med. 2005;33(4):721. PubMed

- Vlaar APJ, Toy P, Fung M, et al. A consensus redefinition of transfusion-related acute lung injury. Transfusion. 2019;59(7): 2465. PubMed

- United States Food and Drug Administration. Transfusion/donation fatalities. 2022. Accessed March 18th, 2023. Link

- Kleinman S, Kor DJ. Transfusion-related acute lung injury. In: Post T, ed. UpToDate; 2023. Accessed March 18th, 2023. Link

Copyright Information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.