Copy link

Transversus Abdominal Plane Block

Last updated: 05/24/2023

Key Points

- Transversus abdominis plane (TAP) blocks are important analgesic interventions that provide significant somatic pain relief to the abdomen.

- The various approaches to the TAP block are differentiated by their probe placement and location of needle insertion and injection, resulting in differences in local anesthetic spread and extent of analgesia.

- Multiple small abdominal wall nerves are the primary target for the TAP block. These nerves are anesthetized by the deposition of large volumes of dilute local anesthetic (20-30 mL per side) across the transversus abdominis fascial plane.

- TAP blocks are technically easy to perform, relatively safe, and best used as adjuncts to multimodal analgesic regimens.

Indications

- The TAP block is often utilized as a part of a multimodal analgesic regimen for abdominal surgeries. Common surgeries where the TAP block has been used include:1

- Open appendectomy

- Open hernia repair

- Total abdominal hysterectomy

- Cesarean section

- Open cholecystectomy

- Laparoscopic abdominal cases

Contraindications

Absolute

- Patient refusal

- Local anesthetic allergy

- Infection at the site of needle entry

Relative

- Severe coagulopathy

Anatomy

Anatomical Considerations

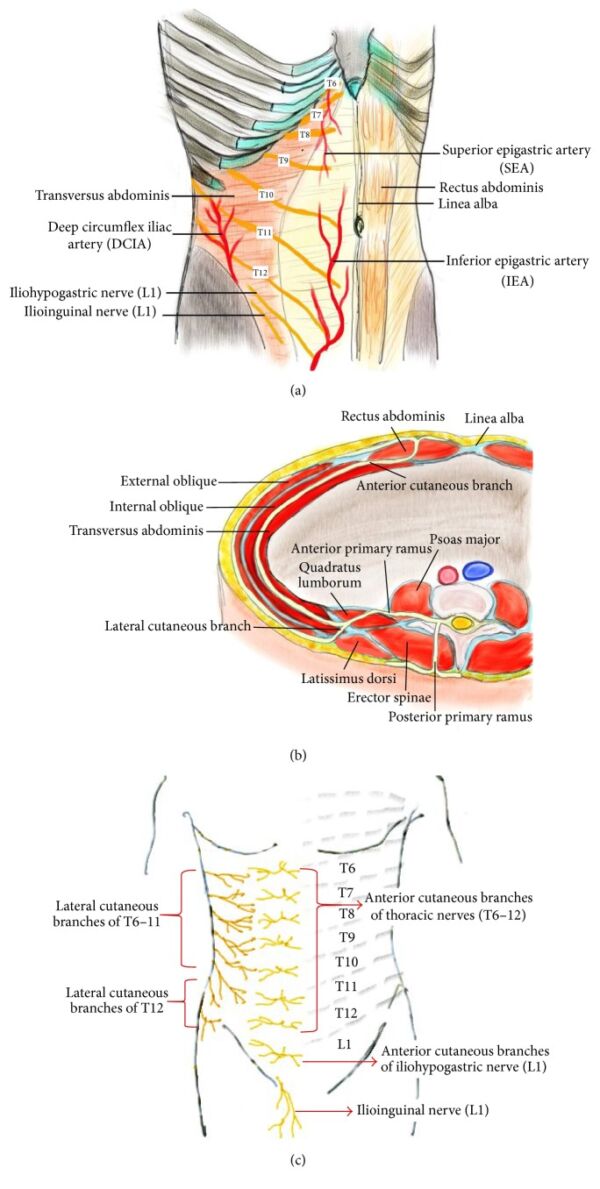

- The anterolateral abdominal wall (skin, subcutaneous tissue, extraperitoneal adipose tissue, abdominal muscles, and parietal peritoneum) lies between the posterior axillary lines on either side. Its superior boundaries are the costal margin of the 7th to 10th ribs and xiphoid process. Its inferior boundaries are the iliac crests, inguinal ligament, pubic crest, and pubic symphysis.

- The anterolateral abdominal wall consists of four paired muscles2: the rectus abdominis, the external oblique, the internal oblique, and the transversus abdominis (Figure 1).

- The paired rectus abdominis muscles run in parallel across the midline.

- Adjacent to the rectus (from superficial to deep) are the external oblique muscle, internal oblique muscle, and transversus abdominis muscle. Fibers of these muscles form an aponeurosis just lateral to the rectus abdominis known as the linea semilunaris. These aponeuroses also form the rectus sheath encasing the rectus abdominis muscle and come together in the midline as the linea alba, a fibrous structure separating the paired rectus abdominis.

- The “TAP” is the fascial plane between the transversus abdominis and internal oblique (lateral TAP), or between the transversus abdominis and posterior rectus sheath (subcostal TAP).

- The transversalis fascia is a thin layer of connective tissue that lines the undersurface of the transversus abdominis muscle, separating it from the parietal peritoneum. It is part of the fascia lining the internal aspect of the abdominal wall, continuing inferiorly with the fascia iliaca and medially as the investing fascia of the quadratus lumborum and psoas major muscles.

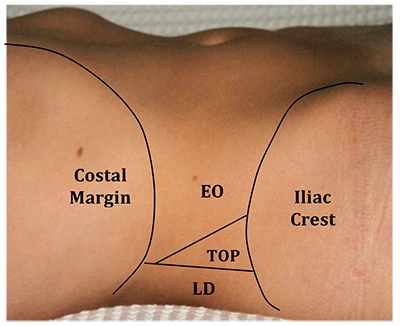

- Prior to ultrasound-guidance, the landmark-guided TAP block involved insertion of the needle posterior to the midaxillary line in the triangle of Petit. The triangle of Petit is bounded posteriorly by the latissimus dorsi, anteriorly by the external oblique, and inferiorly by the iliac crest (Figure 2). This approach uses tactile pops as its endpoint. The first pop indicates penetration through the fascial extension of the external oblique muscle; the second pop indicates penetration through the fascial extension of the internal oblique muscle.

Figure 1. The thoracolumbar spinal nerves (T6-L1) innervating the anterolateral abdominal wall. (a) Anatomy of the anterolateral abdominal wall. (b) Cross-sectional view of the left abdomen. The anterior primary ramus of the segmental nerves divides into anterior and lateral cutaneous branches, which supply the anterolateral abdominal wall. (c) The segmental distribution of cutaneous nerves on anterolateral abdominal wall. Source: Tsai HC, et al. Transversus abdominis plane block: An updated review of anatomy and techniques. Biomed Res Int. 2017; 2017:8284363. CC-BY SA 4.0. PubMed.

Figure 2. Landmarks of the triangle of Petit (EO, external oblique muscle; TOP, triangle of petit; LD, latissimus dorsi muscle). Source: Townsley P, French J. Transversus abdominis plane block anaesthesia tutorial of the week 239. ATOTW, 239, 12-16. CC BY NC ND 4.0. Link.

Cutaneous Supply

- The cutaneous supply of the anterolateral abdominal wall is derived from the anterior rami of the T6 to T12-L1 thoracolumbar spinal nerves.2 Injection of local anesthetic within the TAP can provide unilateral analgesia from T6 to T12-L1 (Figure 1).

- The anterior divisions of the T6 to T12-L1 spinal intercostal nerves exit the intervertebral foramen and travel along their corresponding intercostal space.

- The nerves travel along the lateral abdominal wall within a fascial plane between the transversus abdominis and internal oblique muscle (TAP), before emerging anteriorly to pierce the rectus abdominis muscle and terminate as the anterior cutaneous branches.

- At the midaxillary line, a lateral cutaneous branch comes off and divides into anterior and posterior branches to supply sensation to the skin of the anterolateral and posterolateral trunk.

- The combination of the anterior cutaneous and lateral cutaneous branch innervate most of the anterolateral trunk.

- Vasculature of the anterolateral abdominal wall consists of continuations of the lower thoracic intercostal arteries and the deep circumflex iliac arteries.

- The iliohypogastric and ilioinguinal nerves primarily arise from the anterior ramus of the L1 spinal nerve with occasional contribution from T12. These nerves enter the transversus abdominis plane inferiorly near the anterior third of the iliac crest.

- The iliohypogastric nerve splits into an anterior cutaneous branch which supplies skin near the hypogastrium and a lateral branch that supplies skin over the gluteal region. The ilioinguinal nerve travels within the inguinal canal to supply sensation to the upper thigh, base of penis, and scrotum.

- These abdominal segmental nerves give off branches which communicate at multiple locations within the anterolateral abdominal wall in defined areas known as the upper and lower TAP plexus.3,4 The overlapping contribution of multiple spinal nerves to individual terminal branches may result in a nondermatomal analgesic pattern unless adequate spread of local is achieved.

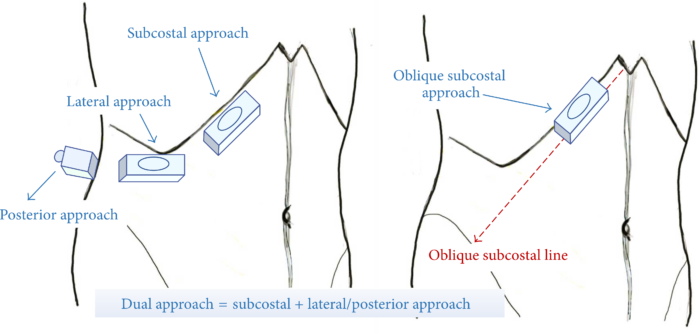

- Various approaches to the TAP block aim to target one or more of these TAP plexuses at different levels of the abdominal wall (Figures 3 and 4).

- The subcostal approach to the TAP targets the upper TAP plexus in between the posterior rectus sheath and the transversus abdominis muscle. Target nerves for the subcostal TAP are the anterior cutaneous branches originating from T6 to T9, innervating the upper abdomen just below the xiphoid and parallel to the costal margin.

- The lateral or midaxillary approach to the TAP targets the lower TAP plexus in between the internal oblique muscle and transversus abdominis muscle. Target nerves for the lateral TAP are the anterior cutaneous branches from T10 to T12 and to a lesser extent, L1.

- The posterior approach to the TAP also targets the lower TAP plexus but at the posterior limit of the TAP plane. Target nerves for the posterior approach are similar to that of the lateral approach but may also include the lateral cutaneous branches. Since the lateral cutaneous branches may be blocked, incisional analgesia can extend lateral to the anterior axillary line, resulting in coverage of most of the truncal surface below the umbilicus.

- A combination of these two approaches (subcostal and lateral/posterior TAP) is termed the 4-quadrant TAP or bilateral dual-TAP block and has been purported to provide analgesia to most of the anterior abdominal wall.

Figure 3. Four approaches of ultrasound-guided transversus abdominis plane (TAP) blocks. Red dashed line indicates the oblique subcostal line, from the xiphoid to the anterior part of the iliac crest. Source: Tsai HC, et al. Transversus abdominis plane block: An updated review of anatomy and techniques. Biomed Res Int. 2017; 2017:8284363. CC-BY SA 4.0. PubMed.

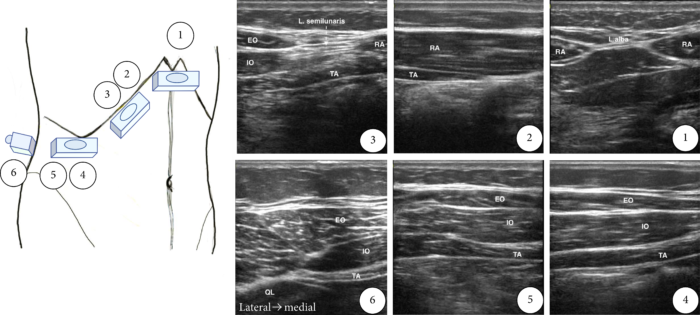

Figure 4. Ultrasound examination of the TAP. RA = rectus abdominis; TA = transversus abdominis; IO = internal oblique muscle; EO = external oblique muscle; QL = quadratus lumborum, L. alba = linea alba; L. semilunaris = linea semilunaris. Source: Tsai HC, et al. Transversus abdominis plane block: An updated review of anatomy and techniques. Biomed Res Int. 2017; 2017:8284363. CC-BY SA 4.0. PubMed

Technique

- The goal of the TAP block is to deposit large volumes of dilute local anesthetic into the transversus abdominis plane. While the TAP block can be performed with a landmark technique, the ultrasound-guided approach provides the benefit of needle visualization, proper spread of local anesthetic, and reduces the chance of injury to other structures. Spread of local anesthetic can be affected by anatomic variation and choice of approach. Choice of approach should be determined on a case-by-case basis, considering the surgery, anticipated incisions, and patient demographics and comorbidities.

Lateral Approach3,4

- A linear transducer is placed in a transverse orientation in the midaxillary line between the subcostal margin and iliac crest.

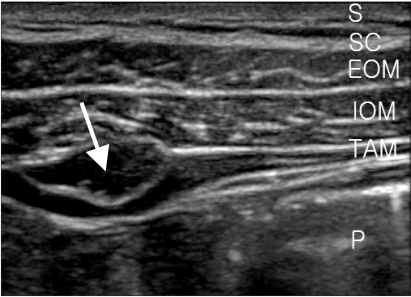

- The transducer is scanned medially to identify the rectus sheath and linea semilunaris, the fascial plane giving rise to the external oblique, the internal oblique, and the transversus abdominis muscles. Scanning laterally will show these three muscles running in parallel to one another (Figure 5).

- A needle is inserted in-plane from anterior to posterior and directed to the transversus abdominis plane in between the internal oblique and transversus abdominis muscles.

- Local anesthetic, in 5 mL increments with negative aspiration for blood, should be slowly injected into this plane.

- If a posterior approach is desired, the ultrasound is moved posteriorly to reveal the transversus abdominis muscle tapering off into a fascial line. Injection occurs at the end of the transversus abdominis plane.

- Correct placement will reveal separation of the transversus abdominis fascial plane with clear formation of a hypoechoic, oval shaped collection of local anesthetic.

- Incorrect placement can be recognized by the lack of clear spread of local anesthetic or patchy opacities appearing within the muscle, indicating that the needle tip is too superficial (internal oblique muscle) or too deep (transversus abdominis muscle).

- Adequate spread of the local anesthetic is ensured by advancing the needle to facilitate unzippering of the plane for optimal analgesic coverage.

Figure 5. Ultrasound view of abdominal muscle and fascia after injection of 1 mL of local anesthetics. Arrow points to transverse abdominis plane. S: skin, SC: subcutaneous tissue, EOM: external oblique muscle, IOM: internal oblique muscle, TAM: transverse abdominis muscle, P: peritoneal cavity. Source: Ra YS, et al. The analgesic effect of the ultrasound-guided transverse abdominis plane block after laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Korean J Anesthesiol. 2010; 58(4), 362-8. CC BY SA 3.0. PubMed.

Subcostal Approach4

- A linear transducer is placed in an oblique orientation along the lower margin of the rib cage.

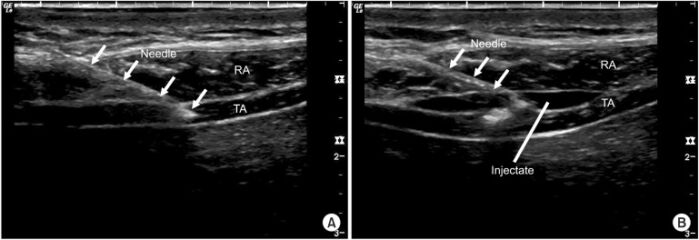

- Scanning towards the midline will reveal the oval shaped rectus abdominis muscle. The aponeurosis of the external oblique, internal oblique, and transversus abdominis should be seen immediately lateral to the rectus abdominis muscle (Figure 6).

- The needle should be directed into the fascial plane between the posterior sheath of the rectus abdominis muscle and the muscle of the transversus abdominis.

- Similar to the lateral TAP approach, correct injection will reveal separation of the fascial plane with clear formation of a hypoechoic, oval shaped collection of local anesthetic.4

Figure 6. (A) Ultrasonography of anterior abdomen during needle insertion for subcostal TAP block. Arrows indicate the shadow of needle. (B) Ultrasonography of anterior abdomen when the injectate starts to hydrodissect the rectus abdominis and transversus abdominis muscles. RA: rectus abdominis, TA: transversus abdominis. Source: Chen CK, et al. A comparison of analgesic efficacy between oblique subcostal transversus abdominis plane block and intravenous morphine for laparascopic cholecystectomy. A prospective randomized controlled trial. Korean J Anesthesiol. 2013;64(6), 511-6. CC BY SA 3.0. PubMed.

Complications

- The TAP block, although considered relatively safe, has a few complications reported in the literature. Such complications include1

- injury to local structures, most notably bowel injury or hepatic injury;

- intraperitoneal injection;

- block failure;

- local anesthetic systemic toxicity; and

- abdominal wall infection.5

References

- Townsley P, French J. Transversus abdominis plane block. Anaesthesia tutorial of the week 239. ATOTW 239 (2011): 12-16. Link

- Elsharkawy H, Bendtsen TF. Ultrasound-guided transversus abdominis plane and quadratus lumborum nerve blocks. In: Hadzic A (ed). Hadzic’s Textbook of Regional Anesthesia and Acute Pain Management. 2nd edition. New York, NY. McGraw Hill. 2017. 642-9.

- Ra YS, Kim CH, Lee GY, et al. The analgesic effect of the ultrasound-guided transverse abdominis plane block after laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Korean J Anesthesiol. 2010; 58(4), 362-8. PubMed

- Chen CK, Tan PCS, Phui VE, et al. A comparison of analgesic efficacy between oblique subcostal transversus abdominis plane block and intravenous morphine for laparascopic cholecystectomy. A prospective randomized controlled trial. Korean J Anesthesiol. 2013;64(6), 511-6. PubMed

- Hang D, Weich D, Anderson C, et al, Severe abdominal wall infection after subcostal transversus abdominis plane block: A case report. AA Practice. 2021; 15(10): e01531. PubMed

Copyright Information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.