Copy link

Pneumonia

Last updated: 09/13/2023

Key Points

- Diagnosis of pneumonia takes into consideration: 1. symptoms (cough, dyspnea, pleuritic chest pain); 2. oxygen requirement; and 3. radiographic infiltrates.

- If possible, sputum and blood cultures should be sent on all patients admitted to the hospital before antibiotics are given.

- Depending on the patient’s history and the targeted organisms, the choice in empiric antibiotics will change.

Introduction

- Pneumonia is an acute infection of the pulmonary parenchyma that can be categorized based on the site of acquisition.1

- Community-acquired pneumonia (CAP): acquired outside health care settings

- Nosocomial pneumonia: acquired in hospital settings, which includes:

- Hospital-acquired pneumonia (HAP): acquired ≥ 48 hours after hospital admission

- Ventilator-associated pneumonia (VAP): acquired ≥ 48 hours after endotracheal intubation

- Health care-associated pneumonia: term no longer used

- Pneumonia can also be classified by etiology.1

- Atypical pneumonia is caused by atypical bacterial pathogens such as Legionella, Mycoplasma pneumoniae, Chlamydia pneumoniae, etc.

- Aspiration pneumonia results from aspiration of gastric or oropharyngeal fluids.

- Chemical pneumonitis commonly results from aspiration of gastric fluid that causes an inflammatory reaction in the lower airways.

- Bacterial aspiration pneumonia caused by bacterial inoculation of aspirated orogastric contents.

- CAP is the second most common cause of hospitalization and the most common infectious cause of death.1

Diagnosis

- Updates to the American Thoracic Society (ATS)/Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) Guidelines (2019) regarding the diagnosis of CAP include:2

- Sputum and blood cultures should be sent on all patients with severe disease as well as in all inpatients empirically treated for methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) and Pseudomonas aeruginosa.

- The use of procalcitonin is not recommended to determine the need for initial antibacterial therapy.

- Chest radiographs should be performed on all patients with the suspicion for pneumonia.

- Radiograph can help to define severity of pneumonia (i.e., multilobar vs. not) and the presence of complications (e.g., effusions or cavitations).

- Additional laboratory studies may include:

- Streptococcus pneumoniae urine antigen should be obtained in all patients with CAP (specificity >95%, positive predictive value 90-95%)

- Some recent studies have questioned its use and noted much lower sensitivity.3

- Legionella urine antigen detects L. pneumophila serogroup 1, which is responsible for 70-80% of Legionella infection.

- Respiratory virus testing should be obtained regardless of time of year if there is a clinical suspicion of respiratory virus infection.

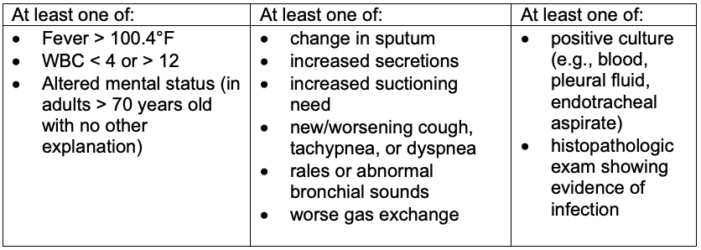

- The criteria for diagnosing VAP is listed in Table 1.4

Table 1. Diagnosis of ventilator-associated pneumonia

- The 2016 IDSA/ATS guidelines recommend noninvasive respiratory sampling for HAP and VAP. In the nonventilated patient, the specimen may be obtained by spontaneous expectoration, sputum induction, or via nasotracheal suction (in uncooperative patients). In the ventilated patient, endotracheal aspirates are preferred.4

- Initial Gram stain and semi-quantitative cultures are used to determine the causative organism(s). Quantities of bacterial growth above a threshold are diagnostic of pneumonia, while quantities below that threshold are likely to be due to colonization. The generally accepted threshold are as follows:4

- Endotracheal aspirates- 106 colony-forming units (CFU)/mL

- Bronchoalveolar fluid- 104 CFU/mL

- Protected specimen brush samples- 103 CFU/mL.

Pathogens

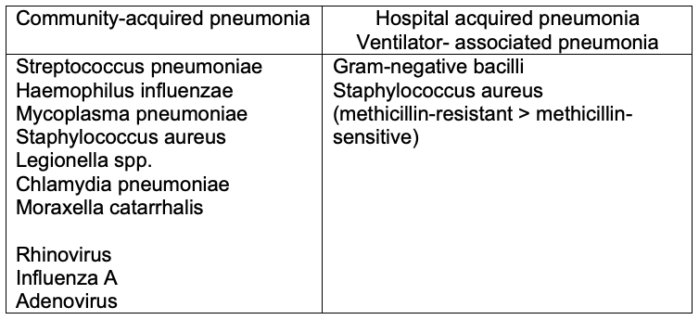

- Common pathogens for pneumonia are listed in Table 2.1,2,4

Table 2. Common pathogens for CAP and VAP

- Epidemiologic and host clues should be used to consider potential pathogens beyond the classic CAP pathogens (e.g., travel exposure, endemic fungi, immunocompromised state, etc.).

Management

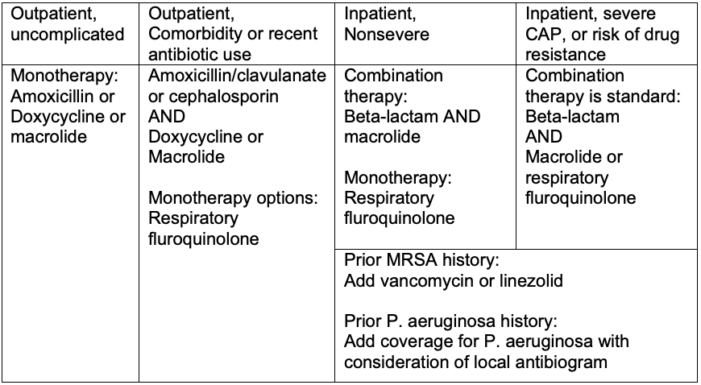

- Treatment of CAP2

- Typically, treatment for no fewer than 5 days is recommended and may be sufficient unless MRSA or P. aeruginosa is present (Table 3). If the patient does not improve, a longer course of therapy (more than 7 days) may be needed.

Table 3. Treatment of community-acquired pneumonia

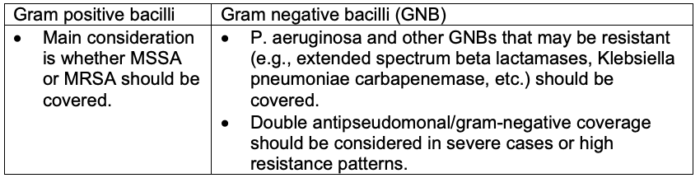

- Treatment of HAP and VAP4

- Most bacterial pathogens in HAP are easily detected by heavy growth on respiratory specimens. Antibiotic considerations are listed in Table 4.

- Sensitivity tests should guide antibiotic choices.

- Duration of treatment is 7 days, although it can be longer.

Table 4. Antibiotic considerations for HAP and VAP

- Prevention of VAP5

- Essential practices for preventing VAP include5

- Intubation and reintubation should be avoided, if possible, by using high-flow nasal oxygen or noninvasive positive pressure ventilation as appropriate whenever safe and feasible (high level of evidence (LOE)).

- Sedation of ventilated patients should be minimized whenever possible. To manage agitation, the use of multimodal strategies and medications other than benzodiazepines is recommended (high LOE).

- Physical conditioning should be maintained and improved by providing early exercise and mobilization (moderate LOE).

- The head of the bed should be elevated to 30-45 degrees (low LOE).

- Oral care should be provided with toothbrushing but without chlorhexidine (moderate LOE).

- Early enteral rather than parenteral nutrition should be provided (high LOE).

- The ventilator circuit should be changed only if visibly soiled or malfunctioning (high LOE).

- Additional approaches include5

- Using selective oral or digestive decontamination in ICUs with low prevalence of antibiotic-resistant organisms (high LOE)

- Using endotracheal tubes (ETT) with subglottic secretion drainage ports for patients expected to require more than 48-72 hours of mechanical ventilation (moderate LOE)

- Considering early tracheostomy (moderate LOE)

- Considering postpyloric rather than gastric feeding for patients with gastric intolerance or at high risk for aspiration (moderate LOE)

- The following approaches are NOT recommended (inconsistently associated with lower VAP rates and no or negative impact on duration of mechanical ventilation, length of stay, or mortality): All with moderate LOE:5

- Oral care with chlorhexidine

- probiotics

- ultrathin polyurethane ETT cuffs

- tapered ETT cuffs

- automated control of ETT cuff pressure

- frequent cuff-pressure monitoring

- silver-coated ETTs

- kinetic beds

- prone positioning

- chlorhexidine bathing

- Essential practices for preventing VAP include5

References

- Ramirez JA. Overview of community-acquired pneumonia in adults. Post T(ed). UpToDate. 2023. Link

- Metlay JP, Waterer GW, Long AC, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of adults with community-acquired pneumonia. an official clinical practice guideline of the American Thoracic Society and Infectious Diseases Society of America. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2019;200(7): e45-e67. PubMed

- Hyams C, Williams OM, Williams P. Urinary antigen testing for pneumococcal pneumonia: is there evidence to make its use uncommon in clinical practice? ERJ Open Res. 2020;6(1):00223-2019. PubMed

- Kalil AC, Metersky ML, Klompas M, et al. Management of adults with hospital-acquired and ventilator-associated pneumonia: 2016 clinical practice guidelines by the Infectious Diseases Society of America and the American Thoracic Society. Clin Infect Dis. 2016:63(5): e61-e111. PubMed

- Klompas, M, Branson R, Cawcutt K, et al. Strategies to prevent ventilator-associated pneumonia, ventilator-associated events, and nonventilator hospital-acquired pneumonia in acute-care hospitals: 2022 Update. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2022; 43(6): 687-713. PubMed

Copyright Information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.