Copy link

One-Lung Ventilation in Children

Last updated: 01/20/2023

Key Points

- The diameter of the left mainstem bronchus is smaller than the right mainstem bronchus in children, and the distance from the carina to the takeoff of the left upper lobe is approximately three times the distance from the carina to the right upper lobe.

- Infants and small children are prone to hypoxemia during one lung ventilation (OLV).

- Common techniques for OLV in children are endobronchial intubation, bronchial blockers, and double-lumen tubes in older children.

Indications for One-Lung Ventilation

Advances in minimally invasive surgical techniques have popularized video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery in children, often necessitating OLV.1 The indications for OLV in children can be broadly categorized to either facilitate surgical exposure or to anatomically isolate a lung.1,2

To Facilitate Surgical Exposure

- Lung surgery: lung biopsy, lobectomy, resection of lung masses

- Pleural surgery: decortication, pleurodesis

- Vascular surgery: PDA ligation, aortic coarctation repair, vascular ring division, aortopexy

- Mediastinal/esophageal surgery: tracheoesophageal fistula, mediastinal mass surgery

- Orthopedic surgery: anterior thoracic spinal fusion, pectus excavatum repair

- Other: congenital diaphragmatic hernia, chest wall mass resection

To Anatomically Isolate a Lung

- To avoid cross-contamination of the healthy lung

- pulmonary hemorrhage, empyema, lung lavage for pulmonary alveolar proteinosis, etc.

- Ineffective ventilation of the ipsilateral healthy lung

- ↓ pressure on the contralateral side: bronchial disruption, bronchopleural fistula

- ↑ lung compliance on one side: unilateral cyst/bullae, congenital emphysema.

Anatomical Considerations in Children

- The diameter of the left mainstem bronchus is smaller than the right mainstem bronchus in children. Thus, a half-size smaller endotracheal tube (ETT) should be selected for left-sided lung isolation.1

- The distance from the carina to the left upper lobe is approximately three times the distance from the carina to the right upper lobe.1 This distance from the carina to the takeoff of the right upper lobe is less than 1cm in most children.

Physiological Considerations in Children

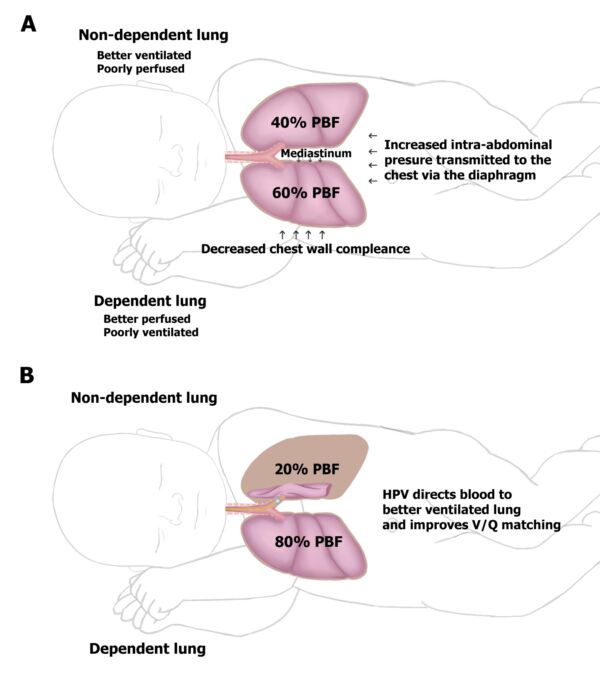

- In the lateral position, the dependent lung is poorly ventilated, secondary to the decreased compliance and functional residual capacity from external compression by the mediastinum, an increase in intraabdominal pressure transmitted to the chest, and a decrease in chest wall compliance (Figure 1).

- In the lateral position, the dependent lung is better perfused because of the redistribution of blood flow. The dependent lung receives about 60% of the pulmonary blood flow, while the nondependent lung receives about 40% of the pulmonary blood flow.

- However, in the lateral position, the nondependent lung is better ventilated but poorly perfused. After the initiation of OLV in the lateral position, the nondependent lung collapses with the distribution of ventilation to the dependent lung. Additionally, alveolar hypoxia in the nondependent lung activates hypoxic pulmonary vasoconstriction (HPV), which redirects blood flow to the better ventilated lung and improves V/Q matching. HPV is a biphasic response that peaks at 15-20 minutes, followed by a secondary delayed response that peaks at 2 hours.

Figure 1. Effects of lateral positioning on the ventilation and perfusion of the lungs in children. Reproduced with permission from Templeton TW, et al. An update on one-lung ventilation in children. Anesth Analg. 2020.1

- Infants and young children are particularly prone to hypoxemia during OLV for several reasons.1

- The mostly cartilaginous rib cage in infants cannot fully support the underlying lung.

- Functional residual capacity in infants is maintained closer to the residual volume, making airway closure in the dependent lung likely to occur even during tidal breathing.

- The mechanical advantage provided by the dependent diaphragm in adults is less pronounced in children.

- Decreased hydrostatic gradient between the nondependent and dependent lung due to smaller size leads to less effective shunting of blood from the nondependent lung to the dependent lung, further worsening V/Q matching.

- Oxygen consumption and metabolic rate are higher in infants and small children.

Techniques for OLV in Children

Endobronchial Intubation

- Endobronchial intubation is the simplest technique to achieve OLV and may be performed by advancing the ETT until unilateral breath sounds are present. The ETT will naturally tend to advance into the right mainstem bronchus and may occlude the right upper lobe takeoff.1

- For left-sided endobronchial intubation, the bevel of the ETT is rotated 180 degrees, and the patient’s head is turned to the right.

- Flexible fiberoptic bronchoscopy (FFB) may be used to facilitate endobronchial intubation and confirm the position of the ETT.

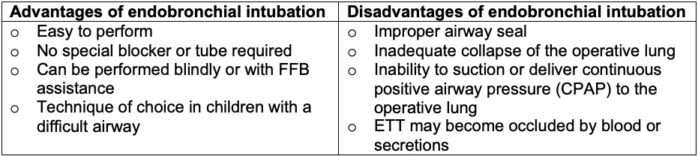

Table 1. Advantages and disadvantages of endobronchial intubation in children.

Bronchial Blockers

- Fogarty catheters and Arndt bronchial blockers (BB) are the most commonly used BBs in children. Less commonly used BBs include Fuji Uniblocker, Univent tube, and EZ-Blocker.1

- The Fogarty catheter has a low-volume, high-pressure balloon that should be inflated with 1.5-3mL of air under direct visualization to avoid overinflation and placing increased pressure on the distal airway. The Fogarty catheter does not have a central channel for suctioning, applying CPAP, or deflating the operative lung. The 2 Fr and 3 Fr Fogarty catheters lack a guidewire, limiting their ability to be angulated and directed into the desired mainstem bronchus.

- The Arndt BB has a high-volume, low-pressure cuff and terminates with a flexible wire loop that may be used as a lariat around the FFB to facilitate positioning. The central channel in the Arndt BB allows for the delivery of O2 and CPAP to the operative lung, and suction may be applied to facilitate lung deflation.

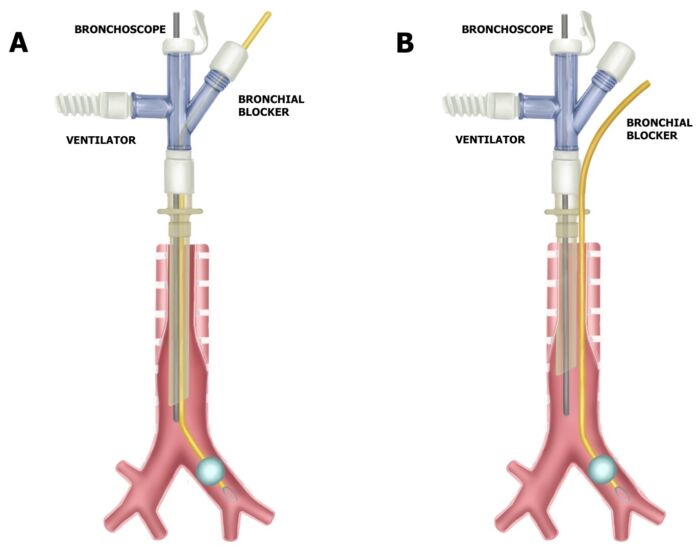

- Arndt BBs are available in three different sizes: 5 Fr, 7 Fr, and 9 Fr. They can be positioned intraluminally or extraluminally (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Intraluminal vs. extraluminal BB placement. Reproduced with permission from Templeton TW, et al. An update on one-lung ventilation in children. Anesth Analg. 2020.1

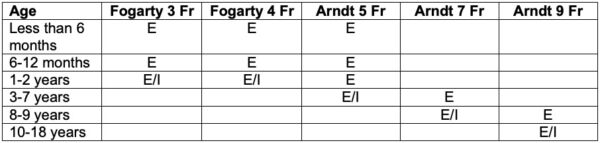

- A 5 Fr Arndt BB and 2.2 mm FFB requires at least a 4.5 ETT. Therefore, the earliest a 5 Fr Arndt BB can be used with an intraluminal approach is a 3–4-year-old child (Table 2).1,3, 4

Table 2. Recommended sizes of Fogarty catheter and Arndt BB for OLV based on age. E = extraluminal, I = intraluminal. Adapted from Templeton TW, Goenaga- Diaz E. One-lung ventilation. In Narasimhan J and Fiadjoe JE, Eds. Management of the Difficult Pediatric Airway. Cambridge UK; Cambridge University Press; 2020: 212-28.4

- There are two popular approaches to extraluminal bronchial blocker placement.

- The Loop Approach involves using the loop of the Arndt BB as a lariat around the ETT and subsequent placement following direct laryngoscopy. A FFB is then passed through the ETT into the desired mainstem bronchus, and the loop of the Arndt BB is advanced over the FFB and into the mainstem bronchus. The loop may move during placement, and it may be difficult to reposition the BB after the bronchoscope is withdrawn.

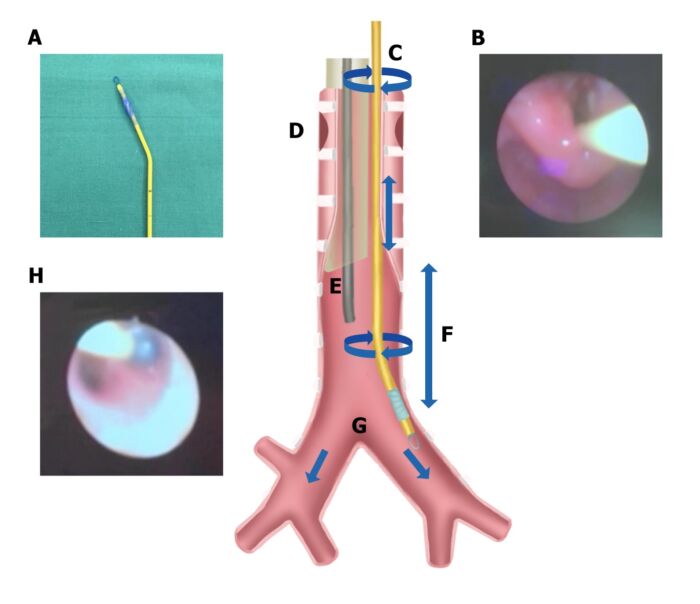

- Bending the Blocker technique involves placing a 30–45-degree bend 1-1.5cm proximal to the distal balloon of the Arndt BB (Figure 3). Following direct laryngoscopy, the BB is placed first and advanced 3-4cm distal to the glottic opening. Subsequently, an ETT is inserted adjacent to the blocker. A FFB is then passed through the ETT and used to visualize the BB, which is then advanced into the desired mainstem via a twisting motion.

Figure 3. Bending the BB approach. A: Arndt BB with 30–45-degree bend. B: Arndt BB advanced into the glottic opening after direct laryngoscopy followed by endotracheal intubation. C: BB manipulated with twisting motion at the mouth opening. E: Fiberoptic endoscope inserted via endotracheal tube. G: BB advanced into desired mainstem bronchus under direct vision. H: BB balloon inflated under direct vision. Reproduced with permission from Templeton TW, et al. An update on one-lung ventilation in children. Anesth Analg. 2020.1

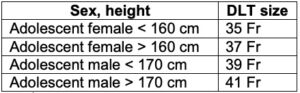

Table 3. Advantages and disadvantages of bronchial blockers.1

Double-Lumen Tubes (DLT)

- DLTs are considered the gold-standard for OLV in adults. Unfortunately, the smallest DLT is 26Fr (roughly equivalent to a 6.5 ETT); therefore, DLTs can only be used in children older than 8-10 years.1

- Following direct laryngoscopy, a DLT is advanced beyond the glottic opening and rotated 90 degrees towards the desired bronchus. Fiberoptic bronchoscopy is recommended to confirm placement such that the bronchial cuff is visualized at the level of the carina.

- While both left-sided and right-sided DLTs are available, left-sided DLTs are typically preferred to prevent occlusion of the takeoff of the right upper lobe.

- The sizing of DLTs depends on the patient’s sex and height (Table 4).1

Table 4. DLT sizing in adolescents.1

Table 5. Advantages and disadvantages of DLTs

Special Situations

OLV in a Child with a Tracheostomy

- Either an endobronchial intubation or an extraluminal BB may be used for OLV in a child with a tracheostomy.1 In small children, the short distance from the tracheostomy stoma to the carina must be considered while positioning the BB or using endobronchial intubation.

OLV in a Child with a Known Difficult Airway

- In a child with a difficult airway, securing the airway takes priority over OLV. The options for OLV are endobronchial intubation or using BBs in older children.1

References

- Templeton TW, Piccioni F, Chatterjee D. An update on one-lung ventilation in children. Anesth Analg. 2021;132(5): 1389-99. PubMed

- Ma M, Slinger PD. One lung ventilation: General principles. Ed: Hines R. UpToDate 2022. Accessed Nov 9th, 2022.

- Downard MG, Lee AJ, Heald CJ, et al, A retrospective evaluation of airway anatomy in young children and implications for one lung ventilation. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2021; 35(5): 1381-7. PubMed

- Templeton TW, Goenaga- Diaz E. One-lung ventilation. In Narasimhan J and Fiadjoe JE, Eds. Management of the Difficult Pediatric Airway. Cambridge UK; Cambridge University Press; 2020: 212-28.

Other References

- Chatterjee D. Pediatric one-lung ventilation. OpenAnesthesia. Published August 2019. Accessed January 20, 2023. Link

Copyright Information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.