Copy link

Herpes Zoster and Postherpetic Neuralgia

Last updated: 06/13/2023

Key Points

- Herpes zoster is a viral syndrome caused by the reactivation of varicella-zoster virus (VZV) previously lying dormant in the peripheral or cranial nerves.

- Postherpetic neuralgia (PHN) is a long-term complication of herpes zoster characterized by lancinating/burning pain in a unilateral dermatomal pattern that persists for three or more months after the onset of herpes zoster.

- Risk factors for developing PHN include increasing age, severe rash, and pain during herpes zoster infection.

- Treatment is focused on aggressive pain management that can include a variety of medications traditionally used to treat neuropathic pain, with strong evidence for gabapentinoids, tricyclic antidepressants, and topical capsaicin.

Herpes Zoster

- Herpes zoster, also known as shingles, is a viral syndrome caused by the reactivation of VZV. After the initial varicella infection or chickenpox in childhood, VZV remains dormant in nerve cells, specifically dorsal root ganglia or cranial nerves.1,2

- Upon reactivation, VZV replicates in neuronal cell bodies, and virions are carried down from the nerve to the area of the skin innervated by that ganglion. In the skin, the virus causes local inflammation and blistering.2

- In the United States, herpes zoster occurs in more than 1.2 million patients annually. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention estimates that approximately 30% of Americans will experience herpes zoster during their lifetime.1

Risk Factors for Herpes Zoster

Risk factors for developing herpes zoster include:2

- Age is the most important risk factor. There is a dramatic increase in the incidence of herpes zoster at approximately 50 years of age, with 40% of the cases occurring in patients older than 60 years. The severity of the disease and complications, such as PHN, also increases with age.

- Immunocompromised patients are at an increased risk of VZV reactivation. This includes patients with organ transplants, hematopoietic stem cell transplants, immunomodulator therapies, autoimmune diseases (rheumatoid arthritis, inflammatory bowel disease), human immunodeficiency virus, etc.

- Other risk factors include female sex, Caucasians, and physical trauma.

Clinical Presentation of Herpes Zoster

- Herpes zoster usually presents with a viral prodrome followed by a rash that starts as erythematous papules in a single or two contiguous dermatomes and becomes grouped vesicles or bullae. The thoracic and lumbar dermatomes are commonly involved, and the rash does not usually cross the midline (Figure 1).1,2

- The rash is usually painful, itchy, or tingly and these symptoms may precede the rash itself. This acute phase lasts about 2-4 weeks.

Treatment of Herpes Zoster

- Antiviral therapy (acyclovir, valacyclovir, famciclovir) is commonly used to hasten the healing of the cutaneous lesions and to decrease the duration and severity of the painful neuritis.2

- Patients with mild pain can be treated with acetaminophen and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs.

- A short course of oral opioids may be needed in patients with moderate to severe pain. There is no clear role for the use of glucocorticoids or tricyclic antidepressants in patients with uncomplicated herpes zoster.2

Postherpetic Neuralgia

- PHN is the most common long-term complication of herpes zoster. The hallmark of PHN is a lancinating/burning pain in a unilateral dermatomal pattern that persists for three or more months after the onset of herpes zoster. The pain can also be severe shooting or electric-like pain.

- More than 90% of patients with PHN report allodynia and hyperalgesia.3

- The pain is localized to a dermatome. Thoracic (T4-T6), cervical, and trigeminal nerves are most commonly affected by PHN.

- PHN can last for weeks, months, or even years.

- The risk of developing PHN after herpes zoster increases with age. Approximately 10-13% of patients 60 years and older with herpes zoster will get PHN.4 On the other hand, the risk of PHN is less than 2% in patients younger than 60 years of age.3

- Other predictors of PHN include the level of pain and the size of the rash.3,4

Treatment of PHN

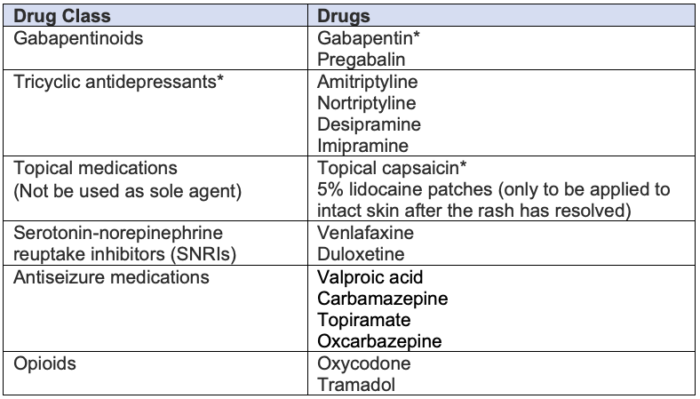

- PHN can be difficult to treat, and patients often multimodal therapy (Table 1).3,5,6 The treatment options should be individualized according to the severity and location of pain, comorbidities, treatment cost and availability, and patient preferences.3

Initial Therapies

- For most patients with moderate or severe pain, a gabapentinoid, such as gabapentin or pregabalin, is often used as initial therapy.

- For patients who do not tolerate or respond to a gabapentinoid, a tricyclic antidepressant, such amitriptyline or nortriptyline is often used.

- Topical therapy with capsaicin is used for patients with mild to moderate and localized pain. Lidocaine patches can be used as an alternative for those who do not tolerate capsaicin. Lidocaine patches should only be applied to intact skin after the rash has resolved.

Alternative Therapies

- For patients who do not tolerate or are unresponsive to initial therapy, an alternative agent is often added. Alternative agents include antiseizure medications and serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (Table 1).

Adjunctive Options

- For patients with refractory symptoms, adjuncts include a short course of opioids, intrathecal glucocorticoid injections, botulinum toxin injections, cryotherapy, neuromodulation, etc.

Table 1. Pharmacological treatment options for PHN. * indicates high level of evidence.

Prevention of PHN

- The primary prevention of PHN is prior vaccination with the varicella vaccine. Vaccination decreases the incidence of virus reactivation and also decreases the severity of herpes zoster if reactivation does occur, and consequently, the incidence of PHN.3

- Secondary prevention is focused on aggressive pain management during the herpes zoster infection, given that severe pain during the acute phase is a predictor for developing PHN.

- The routine use of nerve blocks (peripheral, neuraxial and sympathetic blocks) as a preventive measure for PHN is not supported by strong evidence. A consensus statement by the International Association for the Study of Pain Neuropathic Pain Special Interest Group and by the Neuropathic Pain Institute gave a weak recommendation for the use of epidural or paravertebral blocks with local anesthetic and steroids injections for herpes zoster pain.7

References

- Nair PA, Patel BC. Herpes zoster. In: StatPearls (Internet). Treasure Island, FL. StatPearls Publishing. 2023. Link

- Albrecht MA, Levin MJ. Epidemiology, clinical manifestations, and diagnosis of herpes zoster. In: Post T (ed). UpToDate. 2023. Link

- Ortega E. Postherpetic neuralgia. In: Post T (ed). UpToDate. 2023. Link

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Shingles (Herpes Zoster) Signs & Symptoms. October 5, 2020. Accessed November 30, 2022. Link

- Dosenovic S, Jelicic Kadic A, Miljanovic M, et al. Interventions for neuropathic pain: an overview of systematic reviews. Anesth Analg. 2017;125(2):643-52. PubMed

- Thakur S, Dworkin RH, Thakur R. Herpes zoster and postherpetic neuralgia. In: Fishman S, Ballantyne J, Rathmell J (eds). Bonica’s Management of Pain (5th edition). Philadelphia, PA; Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2019: 372-95.

- Dworkin RH, O’Connor AB, Kent J, et al. Interventional management of neuropathic pain: NeuPSIG recommendations. Pain. 2013;154(11):2249-61. PubMed

Copyright Information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.