Copy link

Factor V Leiden Disease

Last updated: 03/26/2024

Key Points

- A point mutation of the Factor V gene, which codes for an elimination of the cleavage site in Factor V and activated Factor Va, is the underlying cause of Factor V Leiden (FVL) disease.

- The majority of individuals with FVL have a laboratory-only abnormality, as only 5% of patients with FVL develop venous thromboembolism (VTE) in their lifetimes. The main clinical presentation is the presence of recurrent thromboembolism, either arterial or venous in origin.

- Testing for FVL is not indicated for patients with their first diagnosis of deep vein thrombosis (DVT)/pulmonary embolism (PE), as it is too expensive and provides no clinically meaningful benefit. In addition, random screening of the general population for FVL is not recommended. Neither is prenatal testing nor routine newborn screenings. However, there is growing consensus that testing should be performed under certain conditions.

- There is no evidence for altering perioperative management on the basis of FVL, nor is there evidence to support a role of preoperative screenings, though the risk of arterial thrombosis is increased in vascular surgeries.

Pathophysiology

- FVL is the most commonly known inherited cause of thrombophilia and is present in approximately 5% of the Caucasian population.

- A point mutation of the factor V gene, which codes for an elimination of the cleavage site in factor V and activated factor Va, is the underlying cause of FVL disease.1

- Patients are at an increased risk for thrombosis as a result of this genetic defect.

- FVL is inherited in an autosomal dominant pattern with incomplete penetrance. Some patients with the mutation may never have a thrombotic event, while others may develop DVT, cerebral venous thrombosis, or recurrent pregnancy losses.1

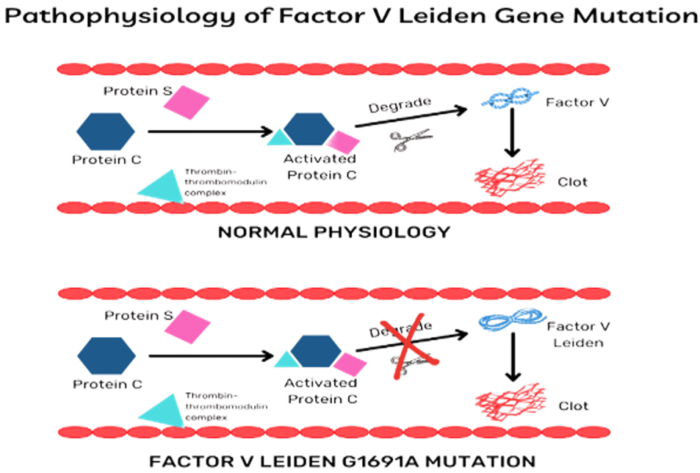

- Normally, activated protein C (APC) and its cofactor protein S, function as a natural anticoagulant by inactivating factors Va and VIIIa, the primary factors implicated in the coagulation cascade.1 With FVL, APC cannot bind and inactivate factor V, which increases the risk of thrombosis (Figure 1).

- FVL is found in 20-25% of patients with VTE and up to 50% of patients with familial thrombophilia.2

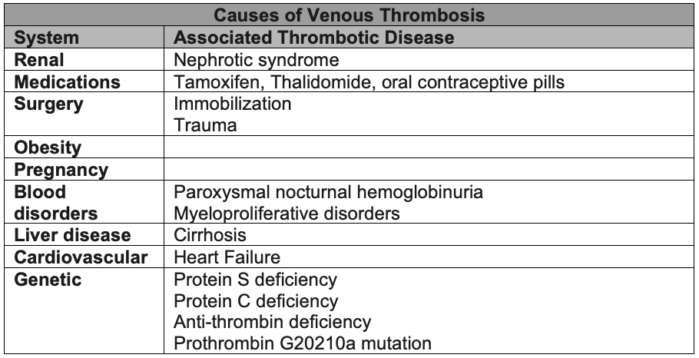

- It is important to identify other common causes of thrombophilia (Table 1).3

- APC resistance accounts for approximately 20% of unselected patients with a first episode thrombosis, as well as 50% of familial thrombosis and 60% of thrombotic patients known to have normal levels of protein S, protein C, antithrombin, and antiphospholipid antibodies.4

Table 1. Common causes of venous thrombosis. Adapted from Reference 3.

Figure 1. Pathophysiology of factor V Leiden gene mutation. Source: Padda J, et al. Factor V Leiden G1691A and prothrombin gene G20210A mutations on pregnancy outcome. Cureus. 2021;13(8):e17185. PubMed

Clinical Manifestations

- The majority of individuals with FVL have a laboratory-only abnormality, as only 5% of patients with develop VTEs in their lifetime.1

- The main clinical presentation is the presence of recurrent VTE, either arterial or venous in origin.2

- There is a slight increased risk of coronary artery disease in patients with FVL, with an increased risk of stroke in female smokers.1

- Recurrent pregnancy losses, hepatic artery thrombosis after liver transplantation, and central venous thromboses are rare clinical manifestations.4,5

Diagnosis and Testing

- Diagnosis is suspected in patients with VTEs as manifested by unprovoked DVT or PE. This is seen particularly during pregnancy in women taking oral contraceptives, or in a patient with a family history of recurrent thromboembolism.4

- FVL may lead to increased thrombin generation beyond the hypercoagulability of pregnancy and contribute to thrombosis and generation of fibrin and fibrin degradation products, causing an overall “inflammatory burden” which leads to pregnancy loss.4,5

- Despite the proposed mechanism, a causative relationship is not well established for FVL. A recent case-controlled study suggested an increased in small for gestational age (SGA) association for pregnant parturients with FVL.4

- According to the American Society of Hematology, testing for FVL is not indicated for patients with their first diagnosis of DVT/PE, as it is too expensive and provides no clinically meaningful benefit. In addition, random screening of the general population for FVL is not recommended. Neither is prenatal testing nor routine newborn screenings.6

- However, there is growing consensus that testing should be performed in the following circumstances based on recommendations from the American College of Medical Genetics:6

- Age younger than 50 years, with any venous thrombosis.

- Venous thrombosis in unusual sites (such as hepatic, mesenteric, and cerebral veins)

- Recurrent venous thrombosis

- Venous thrombosis and a strong family history of thrombotic disease

- Venous thrombosis in pregnant women or women taking oral contraceptives

- Relatives of individuals with venous thrombosis under the age of 50

- Myocardial infarction in female smokers under the age of 50

- Testing may also be considered in the following situations:6

- Venous thrombosis, age older than 50 years, or younger than 50 years if active malignancy is present

- Relatives of individuals known to have FVL disease

- May influence the management of pregnancy

- May be a factor in decision-making regarding oral contraceptive use

- Women with recurrent pregnancy loss or unexplained severe preeclampsia, placental abruption, intrauterine fetal growth retardation, or stillbirth

- Carrier status may influence management of future pregnancies.

- Routine testing is not recommended for patients with a personal or family history of arterial thrombotic disorders (e.g., acute coronary syndromes or stroke) except for the special situation of myocardial infarction in young female smokers.6

- Testing may be worthwhile for young patients (younger than 50 years) who develop acute arterial thrombosis in the absence of other risk factors for atherosclerotic arterial occlusive disease.6

Perioperative and Postoperative Implications

- Venous thrombosis after orthopedic or general surgery does not appear to be increased in the presence of FVL heterozygosity when patients are appropriately managed with established protocols for prophylactic postoperative anticoagulation.7

- There is no evidence for altering perioperative management on the basis of FVL, nor is there is evidence to support a role for preoperative screening.7

- The risk of arterial thrombosis is slightly increased for vascular surgeries, with research identifying benefits of APC screening. However, the decision should be based upon a variety of factors, including surgical urgency and potential risk, patient history, clinical predictors, functional capacity, and specific invasive and noninvasive testing.

- Patients with FVL undergoing cardiac surgery will likely bleed less than their non-FVL counterparts. The bleeding loss would be similar to patients undergoing antifibrinolytic therapy.7

- There is limited literature on the use of lysine analogs, including tranexamic acid and amino-aminocaproic acid, in patients with FVL. However, there are case reports of massive thrombotic events in the setting of FVL, antifibrinolytic therapy and hypothermic circulatory arrest.7

- Aprotinin is known to be an APC inhibitor, though its anticoagulation effects seem to predominate in FVL patients. Therefore, they are recommended when clinically necessary.7

References

- Albagoush SA, Koya S, Chakraborty RK, et al. Factor V Leiden mutation. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2022. Link

- Kujovich JL. Factor V Leiden thrombophilia. 1999 In: Adam MP, Everman DB, Mirzaa GM, et al., editors. GeneReviews® [Internet]. Seattle (WA): University of Washington, Seattle; 1993-2024. Link

- Ornstein DL, Cushman M. Circulation. Factor V Leiden. Circulation; 107(15): e94-7. PubMed

- Padda J, Khalid K, Mohan A, et al. Factor V Leiden G1691A and prothrombin gene G20210A mutations on pregnancy outcome. Cureus. 2021;13(8):e17185. PubMed

- Matei A, Dolan S, Andrews J, et al. Management of Labour and Delivery in a Patient With Acquired Factor VII Deficiency With Inhibitor: A Case Report. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2016;38(2):160-3. PubMed

- Grody WW, Griffin JH, Taylor AK, et al. American College of Medical Genetics consensus statement on factor V Leiden mutation testing. Genet Med. 2001;3(2):139-48. PubMed

- Donahue BS. Factor V Leiden and perioperative risk. Anesth Analg. 2004;98(6):1623-34. PubMed

Copyright Information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.