Copy link

Abdominal Compartment Syndrome

Last updated: 09/20/2023

Key Points

- Intraabdominal hypertension (IAH) is defined as sustained intraabdominal pressures (IAP) ≥ 12 mmHg.1

- Abdominal compartment syndrome (ACS) is a potentially life-threatening illness that results from the persistent and pathological elevation of IAP above 20mmHg that is associated with new organ dysfunction.1

- Delay in treatment of ACS is associated with very high mortality rates.

Introduction

- Compartment syndrome is defined as the elevation of pressures in a fixed body cavity leading to ischemia and organ dysfunction due to the limited compliance of muscular and fascial boundaries.

- ACS refers to the organ dysfunction that results from the elevation of pressures within the abdominal cavity.

- In critically ill patients, IAP of 5-7mmHg is considered normal, although this value can vary dependent on patient factors (e.g., morbid obesity, pregnancy).2

- Elevated IAP can lead to the decrease in abdominal perfusion pressure (APP), which is calculated as the difference between the IAP and the mean arterial pressure (MAP).

- Intraabdominal hypertension (IAH) is defined as sustained intraabdominal pressures (IAP) ≥ 12 mmHg.1

- ACS is defined as the persistent and pathological elevation of IAP above 20 mmHg and can result in fatal organ compromise if not recognized or addressed promptly. Even with delayed treatment, the morbidity and mortality associated with ACS is very high.

Diagnosis

- The diagnosis of ACS can be missed because it primarily affects critically ill patients, in whom the etiology of organ dysfunction may be incorrectly ascribed (Table 1).

- Some of the risk factors associated with ACS include:

- Trauma

- Severe burns

- Liver transplantation

- Abdominal surgery

- Abdominal or retroperitoneal hemorrhage

- Sepsis

- Imaging may help localize a cause of increased IAP (e.g., acute bleeding, trauma, obstruction) but does not diagnose ACS.

- Measurement of IAP:

- IAP can be measured indirectly using intragastric, intracolonic, intravesical, or inferior vena cava catheters.

- The measurement of bladder pressure (i.e., intravesical) is minimally invasive and often used to monitor and diagnose IAH and ACS.

- This is most accurate when the patient is intubated and paralyzed.

- Serial monitoring should involve measuring the pressure consistently (i.e., supine and flat positioning, ventilator settings, paralysis).

- Contraindications to intravesical catheters include bladder trauma, neurogenic bladder, BPH, and pelvic hematoma.

- To measure bladder pressures using a Foley catheter:4

- The drainage tube of the Foley catheter is clamped.

- Sterile saline (up to 60 mL) is instilled into the bladder via the aspiration port of the Foley catheter.

- A pressure transducer is inserted into the aspiration port and zeroed at the level of the midaxillary line.

- Bladder pressures should be measured at end-expiration after ensuring that abdominal muscle contractions are absent.

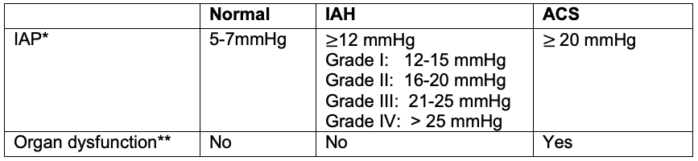

Table 1. Diagnosis and grading of IAH and ACS

Abbreviations: IAP, intraabdominal pressure; IAH, intraabdominal hypertension; ACS, abdominal compartment syndrome

* A general rule of thumb is that patients with IAP less than 10 mmHg are at a low risk for organ compromise, while patients with IAP greater than 25 mmHg are at high risk for ACS.

** Pressure thresholds were established for research purposes, but for clinical purposes, ACS may be better defined as IAH-induced new organ dysfunction without a strict IAP threshold.3

Systemic Effects of Increasing IAP4

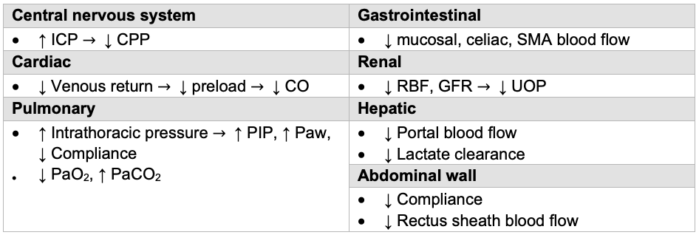

- The systemic effects of increasing IAP are listed in Table 2.

Table 2. Systemic effects of elevated IAP. Abbreviations: ICP, intracranial pressure; CPP, cerebral perfusion pressure; SMA, superior mesenteric artery; CO, cardiac output; CVP, central venous pressure; SVR, systemic vascular resistance; RBF, renal blood flow; GFR, glomerular filtration rate; UOP, urine output; PIP, peak inspiratory pressure; Paw, airway pressure; PaO2, partial pressure of oxygen in the arterial blood; PaCO2, partial pressure of carbon dioxide in the arterial blood.

Adapted from Gestring M. Abdominal compartment syndrome in adults. In: Post T (Ed), UpToDate, Waltham, MA. 2023.

Management

- Nonsurgical options to help alleviate IAH aims to:

- improve abdominal wall compliance (i.e., neuromuscular blockade);

- gastrointestinal decompression (i.e., nasogastric tube and/or rectal tube placement); and

- evacuation of fluid collections (e.g., percutaneous drainage of abscesses, paracentesis).

- Once progressed to ACS, primary treatment is surgical decompression.

- After surgical laparotomy, abdominal fascia is left open until appropriate for closure (i.e., swelling decreased and fascia able to be reapproximated). The aim is for closure within 5-7 days.

References

- Kirkpatrick AW, Roberts DJ, Waele JD, et al. Intra-abdominal hypertension and the abdominal compartment syndrome: Updated consensus definitions and clinical practice guidelines from the World Society of the Abdominal Compartment Syndrome. Intensive Care Med. 2013; 39:1190-1206. Link

- Sanchez NC, Tenofsky PL, Dort JM, et al. What is normal intra-abdominal pressure? Am Surg. 2001;67(3):243-8. PMID: 11270882. PubMed

- Sugrue M. Abdominal compartment syndrome. Curr Opin Crit Care. 2005;11(4):333-8. PubMed

- Gestring M. Abdominal compartment syndrome in adults. In: Post T (Ed), UpToDate, Waltham, MA. Accessed on September 7, 2023. Link

Copyright Information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.